Aorere gold

A few specks of gold, found in the Aorere Valley by a musterer in October 1856, saw more than 2000 men flood into Massacre Bay over the following three years. The gold rush was short-lived, but the region’s new name of ‘Golden Bay’ remained.

A few specks of gold, found in the Aorere Valley by a musterer in October 1856, saw more than 2000 men flood into Massacre Bay over the following three years. The gold rush was short-lived, but the region’s new name of ‘Golden Bay’ remained.

Aorere gold

Edward James and John Ellis, two of the earliest European settlers in the Aorere Valley, stopped by a stream while mustering cattle in October 1856 and James found a small amount of gold.

After further prospecting by G.W.W. Lightband, a digger who had been on the Australian goldfields, it was decided the findings justified a "gold rush". Lightband chaired a meeting in February 1857 at which diggers developed a set of rules later used in goldfields around the country.

William Washbourn was one of many to head to the area from Nelson. With his 11 year old son Harry, William spent several months prospecting. Harry described the start of the gold rush as "a large camping picnic with everyone in the highest spirits, optimistically expecting to make a fortune"1

Prospectors worked the alluvial gravels of goldfields in the Tākaka and Aorere valleys, with Ferntown becoming a boomtown. The Māori settlement at the mouth of the river was known as Aorere, but the growing town there was known as Gibbstown, after William Gibbs who subdivided his land into sections for sale. The Nelson Provincial Government, thinking that a substantial population would develop, had a new town named Collingwood laid out on the plateau. Both names were used for a time but Collingwood prevailed, although Gibbstown was later used as the name of the Rating District.2

In 1857 the settlement consisted of just two tents, but by 1858 successive waves of fortune hunters had arrived. There were seven hotels, and the 1858 Census recorded 700 European and 200 Māori inhabitants. The rush proved short lived, and by 1859 the majority of prospectors had moved on to easier gold in the Buller and Central Otago.3 In September 1861, however, the Otago Witness optimistically reported: "...we have much pleasure in stating that Captain Walker of the "Supply" brought with him from Collingwood, during the last week, no less than 206 ounces of gold....and that accounts from the Aorere state that all industrious men on those diggings are doing well".4

The next large gold rush in the Nelson/Marlborough area came in April 1864, when a rich strike was made in the Wakamarina River. The river gravels were worked out quickly and the rush soon passed, but the greed for gold was to be the cause of the infamous Maungatapu Murders.5

German geologist, Dr Ferdinand von Hochstetter, had estimated in 1860 that about 26,000 acres of the eastern Aorere Valley were rich with gold, although capital and labour would be required to exploit it.6

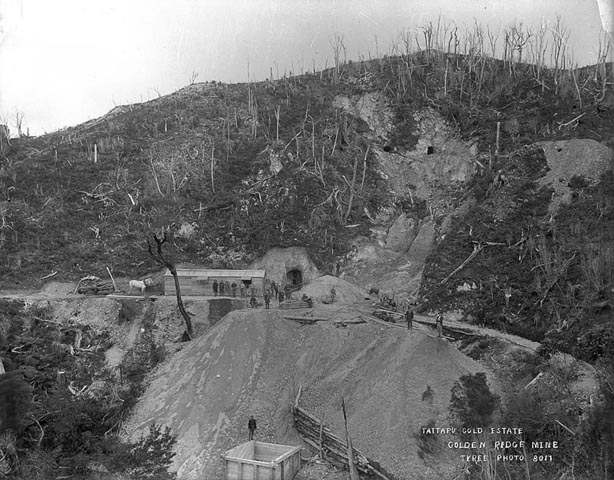

Renewed interest was shown in the possibilities of large-scale sluicing and quartz mining from the early 1880s.7

Several companies built large dams, harnessing water for sluicing. The Collingwood Goldfields Company built a dam at Boulder Lake,8 24 km inland from Collingwood. With eight kilometres of water channels and more than 100 tons of pipes and equipment in place, sluicing began in August 1899. Within a year, however, the company was in liquidation.

The largest of the dams, Druggan's Dam, was developed in 1900 by the Slate River Sluicing Company, which had a large claim between Slate River and Doctor's Creek. Forty men were employed to enlarge George Druggan's original dam. Despite four kilometres of water race, 70 tons of pipe and equipment and three sluicing nozzles, only 1152 ounces of gold were recovered. The company had been wound up by 1909.9

2008

Updated October 12,2021

Story by: Joy Stephens

Sources

- Washbourn, E. (1970). Courage and camp ovens. Wellington, New Zealand: Reed, p 40.

- Newport, J.N.W. (1971). Collingwood : A history of the area from earliest days to 1912. Christchurch, N.Z.: Caxton Press. pp.38-40, 79.

- Washbourn, p. 41.

- Gold fields. (1861, September 7). Otago Witness, p.6.

- McAloon, J. (1997). Nelson: A regional history. Whatamango Bay, N.Z.: Cape Catley. pp. 66-67.

- Our Goldfields. (1860, 4 August) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p2.

- Newport, p.132.

- Dawber, C. (1997). Bainham: a history. Picton, N.Z.: River Press, pp. 69-80.

- Hindmarsh, G. (1995). Water for gold. New Zealand Historic Places, 51(Jan), 19-21.

Further Sources

Books

- Barker, M. T. (1985). Seeker of souls and gold: William Hough, pioneer and prospector. Christchurch, N.Z.: Distributed by Concept Marketing.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154288003 - Bensemann, P. (2013) Lost gold: the 100 year search for the gold reef of Northwest Nelson. Nelson, N.Z.: Craig Potton.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/861763472 - Boyer, J. (2000) There's gold in Rocky. Nelson, N.Z.: Boyer.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154641869 - Caughey, A. (1994) Pioneer families. Auckland, N.Z.: David Bateman Ltd. pp.46-59, the Hough family.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34951119 - Dawber, C. (1997). Bainham: a history. Picton, N.Z.: River Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45116082 - Dawber, C.(2000). Collingwood to the Heaphy Track : a journey up the Aorere Valley. Picton, N.Z.: River Press for the Bainham Reunion Committee.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768634825 - Dawber, C. & Win, C. (2003). Ferntown to Farewell Spit. Picton, N.Z.: River Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156109251 - Dawber, C. & Win, C. (2008) Between the ports. Dunedin, N.Z.: River Press for The Bainham Reunion Committee.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/224088338 - Eldred-Grigg, S. (2008) Diggers, hatters and whores. Auckland, N.Z.: Random House, pp. 48-55.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243861406 - Halket Miller, J. (2003). Beyond the Marble Mountain. Christchurch N.Z.: Cadsonbury Publications.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156262596 - Hodder, E (1863) Memories of New Zealand life. London: Jackson, Walford, and Hodder.

http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document/1863_-_Hodder%2C_Edwin._Memories_of_New_Zealand_Life._2nd_ed.?action=null - McAloon, J. (1997). Nelson: A regional history. Whatamano Bay, N.Z.: Cape Catley.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50310188 - Mitchell, H. & J.(2007). Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough Vol.II, Te ara hou: the new society. Huia Publishers, Wellington, and Wakatu Incorporation, Nelson, N.Z.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/276659471 - Newport, J.N.W. (1971) Collingwood: a history of the area from the earliest days to 1912. Christchurch, N.Z.: Caxton Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/379808 - Neylon, J. & Foster, E. (1989) Bickley family history 1832-1989. Invercargill, N.Z.: J. Neylon.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154271640 (available at Golden Bay Museum Te Waka Hui o Mohua). - Nolan, T (1976). Historic gold trails of Nelson and Marlborough. Wellington, N.Z.: Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7248786 - Salisbury, J. N. (2006). Bush, boots and bridle tracks: the Salisburys: pioneers of the Motueka and Aorere Valleys. Auckland, N.Z.: J. Neville Salisbury.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156378245 - Salisbury, R. (2020). Tableland: the history behind Mount Arthur, Kahurangi Park. Nelson: Potton & Burton.

- http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1224043049

- Shaw, Derek. (1986). Golden Bay walks. Nelson, N.Z.: Nikau Press. pp.32-34.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154607011 - Washbourn, E. (1970). Courage and camp ovens. Wellington, N.Z.: Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/204630 - Washbourn, H.P. (1933). Reminiscences of early days [Nelson, N.Z.] : R. Lucas & Son, Printers.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/153339717

Newspapers

- Few fortunes made in Bay gold quests. (1985, October 12). Nelson Evening Mail, p.8.

- Gold at Collingwood. (1971). New Zealand's heritage, v. 3. Sydney: Hamlyn Paul, pp.691- 695.

- Gold fields. (1861, September 7). Otago Witness, p.6.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=OW18610907.1.6&cl - Harwood, M. (2011) John Vittle [gold miner Upper Tākaka]. Nelson Historical Society Journal. 7(3), p.7.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ07_03-t1-g1-t1.html - Hindmarsh, G. (1995, Jan) Water for gold. New Zealand Historic Places. 51, p.19-21.

- Hindmarsh, G. (2020, December 26). Determination and true grit defined the early days of Golden Bay's golden days. Nelson Mail on Stuff.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/experiences/123786404/determination-and-true-grit-defined-the-early-days-of-golden-bays-golden-days - Our Goldfields. (1860, August 4). Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18600804.1.2&cl=&e - Short, P. (2006, April). New take on an old trail. Wilderness, p. 46-47.

- The Nelson gold fields.(1857, October 14). Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18571114.2.11

Websites

- Walrond , C. (2007, September 21). Gold and gold mining. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/gold-and-gold-mining - Department of Conservation.(n.d.). Aorere Goldfields Track.

http://www.doc.govt.nz/templates/trackandwalk.aspx?id=44540#Plan

Maps

Unpublished/ Museum resources [NPM = Nelson Provincial Museum]

- Barne, J.H.(1986). History of the Taitapu Estate. New Zealand Forest Service. (available at Golden Bay Museum)

- Beach, A. (1932).Goldminer's diary. (available at Golden Bay Museum)

- Berry, Frederick Thomas. (1838-1879). Letters. AG 187.(NPM)

- Hewetson, Thomas. (1857). Letters. qMS HEW (NPM)

- House, William Norman. (1940). The history of the Collingwood district, Nelson Province. MS HOU (available at NPM)

- Jenkin, Robert. Anatoki gold. (available at Golden Bay Museum)

- Mouat, J. The Red Hill swindle (n.d.) (available at Golden Bay Museum)

- Pittams, Grant B. (1977). The historical geography of the Collingwood gold fields. Unpublished master's thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/233648856 (available at NPM, qMSPIT and GBM) - Walker, Kath. (1981). The Quartz Ranges: a brief history. qMS WAL (available at NPM and Golden Bay Museum).