Nelson essentials - water and sewage

‘Bright pure water’ and sewage New Zealand’s early cities reeked of rotting rubbish, dead animals and excrement, and water sources were often contaminated. By contrast, Māori settlements were hygienic, with special sites for toilets and for dumping rubbish, and storehouses which kept food clean.

‘Bright pure water’ and sewage

New Zealand’s early cities reeked of rotting rubbish, dead animals and excrement, and water sources were often contaminated. By contrast, Māori settlements were hygienic, with special sites for toilets and for dumping rubbish, and storehouses which kept food clean. Their used water was disposed of on land, not in waterways.1

As in other parts of the country, providing clean water and dealing with sewage was a challenge for the early European settlers. When the Nelson Provincial Council met on 22 November 1854, they discussed draining the town. ‘It was pointed out that like most newly-formed towns, Nelson began with open drains and cesspools, pigsties, dung heaps, slaughter houses and other pestilential hot beds’, which were polluting air and soil. The need for a water supply was also first mooted at this meeting.2

Clean water

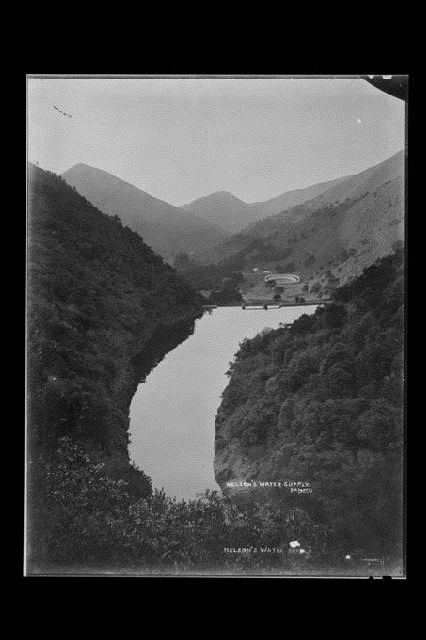

For the first 25 years, Nelsonians made do with dipping cans into local rivers and creeks, catching rainwater, private bores or the water cart for their needs. The idea to use the Brook Stream for a town supply, first raised in 1858, came to fruition on Thursday April 16 1867 when the waterworks were formally opened. The settlement’s “red-letter day” was celebrated in style with a procession, specially composed hymn and prayer, speeches on site and a luncheon. The Brook scheme consisted of a weir and a main pipeline which took the “abundant supply of pure water” to town. The reservoir contained two months supply of fresh water for a population of 7000 people, and was intended to supply the 388 houses in the Nelson township and along Haven Road to the Port.3 However, before long, demand exceeded supply and by the turn of the century there were some serious problems.

In 1904 the “Big Dam” was constructed on the Brook to meet increasing demands, and The 1906 Cyclopedia described the ‘bright and pure water…suitable for all domestic purposes without filtering’ and went on to say that extensive additions had been made by the Nelson City Council including a new concrete storage dam to contain about 20 million gallons of water.4 However, by 1908 it had a serious leak. An upper level weir relieved problems for a time but by the 1920s a common complaint was “water flows over the dam but doesn’t come out our taps!”5

New ancillary mains and pipes were installed in 1922, improving the situation. But a series of long hot summers in the late 1920s saw Nelson’s water supply hover between inadequate and desperate. Bore holes were put down in various places. A bore hole near the Normanby Bridge resulted in such a good supply of water that the Council invested in a larger pump to link this supply into the City’s mains. By 1933, the city’s population had reached 12,000 and it was again difficult to maintain the water supply during the summer.5

The Hume Pipe Company proposed a regional scheme tapping the Roding River and supplying Nelson, Richmond and parts of the Waimea (Tasman) County. This was rejected by the Nelson City Council, but they agreed when the Government made a grant of £25,000 towards the scheme which meant Nelson did not have to share control with Waimea County. The Roding Valley Waterworks has supplied water to Nelson and Richmond residents since 1941, with a low dam and two kilometre pipeline through the hill to Stoke, and to the City via a “break-pressure tank” atop

the Port Hills.5

By 1958 a dam on the south branch of the Maitai was proposed, something which had been discussed since the 1930. The pipeline to the City was constructed, but the dam delayed in favour of a temporary, rock-walled intake. The Maitai Dam and water scheme was completed in 1987 and is now Nelson's main source of water, and the water is treated at the Tantragee Water treatment plant.

Sewage and Sewerage

The first meeting of the Nelson City Council was held in April 1874 and responsibility for providing and maintaining the facilities of a civilised city passed on to this body.6 In 1877, Nelson’s system of sewers had improved but by 1879, the sanitation of the city was far from perfect.7

Funds were low, the Council didn’t want to borrow money and ratepayers didn’t want money spent. In 1890, the neglect of proper sanitation resulted in a severe typhoid epidemic with many cases traced to Hardy Street where the sewer was known to be defective.8

In 1894, Councillor Akersten suggested that the city be drained by a ‘separate system’ where sewage was dealt with separately from surface water, but nothing was done for another ten years.9 The Harbour Board objected to the proposal of draining effluent into the harbour’s tidal waters.10

“How any sane man can advocate the discharge of sewage on the mudflat is beyond my comprehension,” wrote a newspaper letter writer in 1903, describing what had happened in Wellington, Auckland and Dunedin where ‘the odor of putrid festering sewage is a constant menace to life and health.”11

An earlier letter writer in 1884 had idealistically described a ‘sewage farm’ from which tons of dairy produce, splendid orchards and a fine public garden would benefit.12

The 1906 Cyclopedia described a city ‘drained by brick main sewers through the principal streets…with the main outfall into the sea.’ Households not connected to the sewers used a night soil service.

The Cyclopedia noted that a loan of £55,000 had recently been authorised by ratepayers for a complete up-to-date system of sewers designed by Mr R.L. Mestayer.13 By 1907 a septic tank, powerhouse, outfall sewer and ejector chamber were under construction.14

But problems still remained. In 1909 a petition was circulated, drawing attention to ‘the insanitary state of the foreshore at Halifax Street caused by the filth from the sewer being discharged from the overflow at the junction of Waimea and Halifax Streets……We feel justified in urging the Council to take immediate steps to remedy the evil and so save the spreading of diphtheria, scarlet fever and other complaints.”15

Water pollution in New Zealand increased throughout the 19th Century but it was slow to gain national attention and action. In the 1950s, 27% of the population was not connected to a sewer and about 40% of sewage was going untreated into the sea.16 Today, all of Nelson’s effluent is treated before being discharged out to sea at the Nelson wastewater treatment plant.17 Nelson's sewage is treated at the Bell's Island Sewage Treatment Plant.

2016 (updated 2022)

Story by: Joy Stephens

Sources

- Dann, C. (updated 13-Apr-16) Sewage, water and waste. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/sewage-water-and-waste - Broad, L. (1892) The Jubilee History of Nelson: From 1842 to 1892. Nelson: Bond, Finney & Co., p. 119

- Water supply (1861, June 12). Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. p.3

- 1906 Cyclopedia, Nelson Corporation:

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d1-d4.html - Bell, C.W.(1979) Unfinished business: the second fifty years of the Nelson City Council. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson City Council, p 50-52.

- Grace, A.A. (1924) The jubilee history of the Nelson City Council, 1874-1924. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson Mail

- Grace, pp.6-7

- Grace, p.14

- Grace, p.19

- Grace, p.26

- The drainage proposals (1903, September 7) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

- Our sanitary difficulty (1884, March 15) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

- 1906 Cyclopedia

- Grace, p.28

- Sewage on the city foreshore (1909, October 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

- Dann, C. (updated 13-Apr-16) Sewage, water and waste - Water pollution. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/sewage-water-and-waste/page-8 - Wastewater. Retrieved from Nelson City Council, 11 June 2016:

http://nelson.govt.nz/services/rubbish/wastewater/

Further Sources

Books

- Bell, C.W. (1979) Unfinished business: the second fifty years of the Nelson City Council. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson City Council, pp.50-52.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/unfinished-business-the-second-fifty-years-of-the-nelson-city-council/oclc/34523816 - Broad, L. (1892) The Jubilee History of Nelson: From 1842 to 1892. Nelson: Bond, Finney, and Co.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-LowJubi.html - Grace, A.A. (1924) The jubilee history of the Nelson City Council, 1874-1924. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson Mail

http://www.worldcat.org/title/jubilee-history-of-the-nelson-city-council-1874-1924/oclc/154280513 - Maitai water supply scheme (1987) Nelson (N.Z.). City Council.

- Nelson's water supply: Nelson (N.Z.). City Council. [Box contains various Nelson City Council reports on water from 1991 to 1998.] Nelson Public Libraries

Newspapers

Sewage:

- City Council (1902, January 24) Colonist, p.3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TC19200124.2.9 - City drainage proposals (1903, September 7) Colonist, p.1

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TC19030907.2.34 - The drainage proposals (1903, September 7) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM19030907.2.11 - In Nelson (1900, May 10) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM19000510.2.11.2 - Our sanitary difficulty (1885, March 15) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM18840315.2.10.2 - The sewage farm (1885, December 16) Nelson Evening Mail, p.4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM18851216.2.16 - Septic tank drainage (1902, October 18) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM19021018.2.9 - Sewage on the city foreshore (1909, October 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NEM19091021.2.16

Water

- Brown, R. (1993, June 11) Water quality may cost Nelson $15m. Nelson Evening Mail, p.1

- Collett, G. (1999) Water on the brain. Nelson Mail, p.17

- Nichol, R. (1982, October 2) Why south branch water is vital. Nelson Evening Mail, p.4 (part 1 of 2 part series on Maitai Dam - part 2, Nelson Evening Mail, 1982, October 4, p.10; part 3 Nelson Evening Mail, 1982, October 5, p.8; part 4 Nelson Evening Mail, 1982, October 6, p.12; part 5 Nelson Evening Mail, 1982, October 7, p.16 )

- Water supply. To the Editor of the 'Nelson Examiner.' (1862, August 27) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p.3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18620827.2.11.1 - Water supply (1861, June 12) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p.3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18610612.2.10

Websites

- Dann, C. (updated 13-Apr-16) Sewage, water and waste. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/sewage-water-and-waste - Wastewater. Retrieved from Nelson City Council, 11 June 2016:

http://nelson.govt.nz/services/rubbish/wastewater/

![Trafalgar Street, Nelson, [ca 1860], Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-8964-01.](https://backend.theprow.org.nz/assets/society/TrafalgarStreet1.jpg)