The first meeting - Abel Tasman and Māori in Golden Bay / Mohua

When the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman sailed into Golden Bay / Mohua in 1642, a brief violent encounter with local Maori appears to have resulted from mutual cultural misunderstanding

When the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman sailed into Golden Bay / Mohua in 1642, a mutual cultural misunderstanding may have been one reason for the brief violent encounter with local Māori.

Abel Tasman in Golden Bay / Mohua

Abel Janszoon Tasman commanded a Dutch East India Company expedition to discover more about “South Land,” the great southern continent that included the already charted coastline of much of Australia.1 He left Batavia in 1642 with the ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen, making landfall at Mauritius and discovering and charting Van Diemen’s Land 2 before sighting Te Tai Poutini, the South Island’s West Coast.

By the time the Dutch had rounded Onetahua into Mohua (Golden Bay / Mohua) on the night of December 17, 16423 waka are believed to have followed them in the darkness. The fires and smoke the Dutch crew reported seeing along the coastline are likely to have been a succession of signal fires lit by Māori of the dominant tribe, Ngāti Tumatakōkiri, warning settlements ahead of the approach of the strange ships.4

The following morning Tasman sent small boats out to look for a better anchorage and a watering place and that evening the ships anchored somewhere off Wainui Inlet.5 Doubtless Ngāti Tumatakōkiri would have been assessing throughout the day the threat posed by the strange pale men and their vessels.6

Tasman’s journal records that four waka paddled towards them and that there were calls between the vessels. A warrior “blew several times on an instrument…we then ordered our sailors…to play them some tunes in answer.”

It has been suggested that cultural misunderstanding was at the heart of this first contact between Māori and European. Māori may have challenged the ships because they believed the white people were patupaiarehe, fair-skinned fairy folk or ghosts, who were feared because they took women and children away. The shell trumpets may have been blown to scare them away. Imagine the surprise when the ghosts apparently accepted their challenge.7

But it was when the Dutch fired a cannon, that Ngāti Tumatakōkiri must have really got a fright. The resulting explosive boom has been described as a "sonic event" 8 and Māori fled in their waka back to shore. Tasman's men kept a close guard overnight.9

There have also been suggestions that Māori were simply guarding their territory from attack. Ngāti Tumatakōkiri had crossed from the North Island to Te Tau Ihu (Top of the South Island) in the mid 16th century, becoming involved in skirmishes with other tribes already living there. By the late 16th century, the tribe was strongly established in various communities around Golden Bay / Mohua and as far south as Te Tai Poutini (the West Coast of the South Island).10

But Ngāti Tumatakōkiri was subjected to successive retributive raids from other tribes throughout the 17th century (and beyond into the 19th century) and was on alert. So, when strange vessels arrived with white men it is not surprising that communities would rally together to fend off a possible attack.11

There are a number of other factors that may have contributed to the violence that was to follow. The first is that Tasman arrived in the middle of the kūmara (sweet potato) growing season. kūmara was a vitally important food source and one which Māori would have fiercely protected.12 Another is that the Dutch anchored close to the cove and cave of the taniwha Ngārara Huarau and it could be that the superstitious Māori were concerned about the intruders waking the spirit of the dreaded supernatural creature.13

The large number of waka and paddlers recorded by Tasman in his journals also indicates more people than were understood to have lived in the immediate area were in the bay at the time. Rather than the separate Ngāti Tumatakōkiri communities gathering because of the strangers in their midst, it is possible that Tasman happened to arrive in the middle of a large tribal gathering, perhaps a hui (meeting) or tangi (funeral). 14 Lastly, it is possible that stories of European seafarers and their harsh treatment of native peoples in the Pacific had already reached New Zealand and the arrival of men who matched their descriptions was met with a decision to make a pre-emptive strike against the potential threat stories the Dutch posed.15

The next day, December 19, a waka returned, with its crew giving a “rough loud” call, possibly a haka resulting from the exchange of ritual challenges the previous evening. Tasman’s men, misunderstanding the chant’s intent, unsuccessfully tried to encourage them closer, waving linen and knives and calling out. The Māori eventually returned to land and Tasman decided to move the ships closer inshore, as “these people apparently sought our friendship”.16

Before this could be done, two waka paddled out to the ships. While the Dutch crews continued encouraging the Māori to board, a small boat moved from the Heemskerck to the Zeehaen to warn its crew to be on guard and not to let too many aboard. On the boat’s return trip, a waka rammed it and a warrior clubbed Cornelis Joppens on the neck with a long blunt pike, knocking him overboard. Four sailors were killed and the body of one was dragged into a waka. Both waka sped back to shore as the Dutch fired at them with muskets and guns. Cornelis Joppens and two other survivors swam back to the ships and the boat and bodies were retrieved.17

Tasman decided to leave Mohua immediately “since we could not hope to enter into friendly relations with these people, or to be able to get water or refreshments here.”18

As the ships sailed for Cook Strait, eleven waka paddled towards them. A man standing in a large waka held a small white flag, possibly a peace sign, but as they drew closer, Tasman’s men fired, hitting and felling him.19

Tasman named the bay Moordenaers (Murderers) Bay and recorded that the meeting “must teach us to consider the inhabitants of this country as enemies…”20

While Tasman had been warned of the possibility of attack, Māori had experienced a number of bewildering firsts – firearms, tall ships and white men. It would be more than 120 years before Māori and European next met, with the arrival of James Cook in 1769.21

2008 (Revised 2020)

Note - In 2015 there has been renewed scholarly debate around the age of Taupo Pa, and the significance of Wainui Bay in the events of 18/19 December 1642 as shown in a 1705 engraving. References to articles discussing this is provided in the sources below

Update started, February 24, 2025

Story by: Karen Stade

Sources

- Salmond, A. (1991). Two worlds. Auckland, N.Z.: Viking/Penguin, p.71.

- Grahame Anderson (2001). The Merchant of the Zeehaen, Isaac Gilsemans and the voyages of Abel Tasman. Wellington: NZ., Te Papa Press.

- Mitchell, H. & J. (2004). Te ao ihu o te waka: a history of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough. Volume 1: te tangata me te whenua - the people and the land. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia, p.142.

- Mitchell, H & J (2012) Who were Ngati Tumatakokiri?, part of the Abel Tasman 270 Seminar, Nelson, June 15, 2012

- Mitchell (2004) p.142, 144, 146.

- Mitchell (2012).

- Mitchell (2004) p.146.

- Nunns. R. (2012). Did the musical exchange contribute to the disaster the next day?', part of the Abel Tasman 270 Seminar, Nelson, June 15, 2012; Nunns, R. & Thomas, A. (2011). A first encounter in New Zealand. In World music is where we found it - essays by and for Allan Thomas. Wellington, N.Z. : Victoria University Press.

- Mitchell (2004) pp.142-143 ; Salmond, pp.78-79.

- Mitchell (2012).

- Mitchell (2012).

- Barber, I. (2012). Engaging archaeology and historical anthropology to research the Tasman expeditionary records of Dutch and Maori interactions', part of the Abel Tasman 370 Seminar, Nelson, June 15, 2012.

- Mitchell (2004). p.146.

- Mitchell (2012).

- Mitchell (2004), p.146.

- Salmond, p.79,81. ; Mitchell (2004) p.144.

- Salmond, pp.81-82.

- Mitchell (2004). p.144.

- Salmond, pp.81-82.

- Mitchell (2004). p.144.

- Jenkin, R. (2000). Strangers in Mohua: Abel Tasman’s exploration of New Zealand. Takaka, N.Z.: Golden Bay Museum, p.23. ; Salmond, p.82, 84,87.

Further Sources

Books

- Anderson, G. (2001). The merchant of the Zeehaen : Isaac Gilsemans and the voyages of Abel Tasman. Wellington: Te Papa Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/47791111 - Baker, M. (1996). Perrine's park: An environmental, ecofeminist history of the creation of Abel Tasman National Park. B.A. (Hons.) thesis. Dunedin: University of Otago.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/152477547 - Beaglehole, J.C (ed.) (1961). The journals of Captain James Cook. Volume II. The voyage of the Resolution and the Adventure 1772-1775. London: Cambridge University Press.

https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/1052134114 - Dennis, A. (1985). A park for all seasons: The story of Abel Tasman National Park. Wellington, N.Z.: N.Z. Lands and Survey.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/park-for-all-seasons-the-story-of-abel-tasman-national-park/oclc/82758845 - Ell, G. (1992). Abel Tasman: in search of the Great South Land. Auckland, N.Z.: Bush Press.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/abel-tasman-in-search-of-the-great-south-land/oclc/39716365 - Ell, G., & Ell, S. (Eds.). (2008). Explorers, whalers & tattooed sailors: adventurous tales from early New Zealand. Random House New Zealand.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/271815602 - Ell G. & Ell S. (2021). First encounters: New Zealand 1642-1840. Oratia Books Oratia Media.

https://worldcat.org/en/title/1246624627 - Heeres, J. (1898). Abel Janszoon Tasman's journal of his discovery of Van Diemens Land and New Zealand in 1642. Amsterdam: Frederick Muller & Co.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7995144 - Hodge, R. (1993). Creating a park: Perrine Moncrieff and the Abel Tasman National Park: a research essay submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/creating-a-park-perrine-moncrieff-and-the-abel-tasman-national-park/oclc/980540909 - Horry, D. (2018). Two voyages, one encounter: the first meeting of Māori and Europeans and the journeys that led to it. The Copy Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1037244746 - Jenkin, R. (2000). Strangers in Mohua: Abel Tasman's exploration of New Zealand: an investigation of the first recorded contact between Māori and Pakeha, December 18th and 19th, 1642. Tākaka [N.Z.]: Golden Bay Museum.

https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/154317264 - Mack, R. (2024). First Encounters: The Early Pacific and European Narratives of Abel Tasman’s 1642 Voyage. Heritage Press NZ.

https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/1478306337 - McCormick, E. (1959). Tasman and New Zealand a bibliographical study. Wellington, N.Z., R.E. Owen, Govt. Printer.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/tasman-and-new-zealand-a-bibliographical-study/oclc/865622782 - Mitchell, H. & J. (2004). Te tau ihu o te waka: a history of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough. Volume 1: te tangata me te whenua - the people and the land. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/te-tau-ihu-o-te-waka-a-history-of-maori-of-nelson-and-marlborough-volume-4-nga-whanau-rangatira-o-ngati-tama-me-te-atiawa-the-chiefly-families-of-ngati-tama-and-te-atiawa/oclc/1009142678 - Nalder, B. (ed.) (2008). Torrent Bay: Abel Tasman National Park (new ed.). Nelson, N.Z.: Bud Nalder.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/torrent-bay-abel-tasman-national-park/oclc/166311553 -

O'Malley, V. (2012). The meeting place: Māori and Pākehā encounters, 1642-1840. Auckland University Press.

- Salmond, A. (1991). Two worlds. Auckland, N.Z.: Viking/Penguin.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/two-worlds-first-meetings-between-maori-and-europeans-1642-1772/oclc/1013725008 - Sharp, A (1969). The voyages of Abel Janszoon Tasman. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/voyages-of-abel-janszoon-tasman/oclc/717478200 - Simpson, P. (2018). Down the bay: A natural and cultural history of Abel Tasman National Park. Potton & Burton. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1049790282

- Slot, B. (1992). Abel Tasman and the discovery of New Zealand. Amsterdam: O. Cramwinckel.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/abel-tasman-and-the-discovery-of-new-zealand/oclc/30029725 - Smith, D. (1997). Abel Tasman area history. Nelson, N.Z.: Dept. of Conservation, Nelson Marlborough, p.8.

https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/historic/by-region/nelson-marlborough/abel-tasman-area-history-whole-document.pdf - Vigeveno, M. (1942). Abel Janszoon Tasman and the discovery of New Zealand, 1642. Wellington, N.Z.: Department of Internal Affairs.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/abel-janszoon-tasman-the-discovery-of-new-zealand-an-extract-from-tasmans-journal-translated-by-mf-vigeveno-with-an-introduction-by-john-c-beaglehole-with-illustrations/oclc/562249553

Newspapers

[Where no hyperlink is supplied ask at your local library about full text access to the articles.]

- Barber, I. (1992, Dec.). First contact in Golden Bay. New Zealand Historic Places, 39: p.49-51.

- Basham, Laura (2000, 31 January). ‘Dutch “at peace with Māori”. ‘Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Clark, Karen (2000, 1 February). Abel Tasman statue row ends in peaceful unveiling. Nelson Mail, p. 1

- Collett, Geoff (2000, 27 January). Compromise means statue ceremony on. Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Collett, Geoff (2001, 24 January). Second tribe backs protest over statue. Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Courtney, David (1999, 13 November). Tasman welcomed back to Nelson. Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Dick, A. (2007, Aug./Sep.). The Abel Tasman. N.Z. today. 23: p.96-98,101.

- Dutch group coming for statue unveiling (2000, 19 January). Nelson Mail, p.5.

- Glossary of coastal names, (1976, Aug.). Journal of the Nelson Historical Society. 3(2): p.22-27.

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ03_02-t1-back-d1.html - Griffith, P. (2013) Abel Tasman's visit to golden Bay: new insights. Nelson Historical Society Journal 7(5), p. 52

- Hilhorst, M. (1992, 17 Dec.). Park’s popularity brings problems, Press:p.13.

- Hodge, R. (1998, Aug.). Early Birder: Perrine Moncrieff, a woman pioneer in conservation. Forest and Bird, 289: p.28-31.

- Hindmarsh, G. (2017, December 16). Commemorating our first encounter. Nelson Mail, p. 8.

- Hunt, Tom (2008, 19 January). Statue reunited with sword. Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Hutton, Catherine (2000, 2 February). Iwi disgusted by statue vandalism. Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Mack, Rudiger. (2004). Did Dutch sailors land in Wainui Bay on 18 December 1642? Turnbull Library Record, 37, p. 13-28.

- Mayor backs move to Golden Bay for statue (2008, 3 May). Nelson Mail, p.1.

- McDowall, R. (2015, September 4) Historian scrutinises Tasman's voyage and visit to Wainui. Golden Bay Weekly. [PDF]

- Sculptor searches for Tasman’s image (1998, 24 November). Nelson Mail, p.2.

- Sea views for statue’ (1998, 29 January). Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Sivignon, C. (2017, October 1) Commemoration plans of first encounter between Abel Tasman, Māori 375 years ago. Nelson Mail on Stuff

https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/destinations/nz/97210590/commemoration-plans-of-first-encounter-between-abel-tasman-mori-375-years-ago - Statue of Abel Tasman planned (1997, 22 December). Nelson Mail, p.6.

- Sword won’t be replaced (2003, 11 December). Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Tasman armed once more (2001, 6 April). Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Tasman’s artist subject of book (2002, 4 February). Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Yarwood, V. (2005, Mar / Apr.). Abel Tasman: The search for Terra Australis Incognita and the discovery of Zeelandia Nova. New Zealand Geographic, 72: p.64-77.

The Taupo Pā/ Wainui Bay debate:

- Anderson, C. (2015, March 7) New claim rejected by scholar. Nelson Mail. Retrieved from Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/67081063/New-claim-rejected-by-scholar - Anderson, G. (2005) Letter to the editor. Did Gilsemans and Tasman collude in concealing evidence in Batavia in 1643. Alexander Turnbull Record, pp. 93-96

- Mack, R. & Hawarden, R. (2014) A possible pre-Tasman canoe landing site, or 'tauranga waka', in Golden Bay, South Island, New Zealand [online]. AIMA Bulletin,38, pp. 111-124.

http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=808326742292178;res=IELENG - Mack, R. (2006) The source of the first printed illustration of New Zealand. Turnbull Record, 39, 75-82

- Schouten, H. (2015, February 18) Golden Bay canoe site may be oldest structure. Nelson Mail. Retrieved from Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/66323891/Golden-Bay-canoe-site-may-be-oldest-structure

Websites

- Mitchell, H & J (2008) Te Tau Ihu tribes. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/te-tau-ihu-tribes - Simpson, K. A. (2007) Tasman, Abel Janszoon. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography:

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t17/tasman-abel-janszoon - Wilson, John (2008) European discovery of New Zealand. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/european-discovery-of-new-zealand

Maps

- Abel Tasman 370 seminar. Hosted by the Netherlands Ambassador, Mr Arie van der Wiel (2012, June 15). Seminar papers and programme. [held Elma Turner Library].

- First Encounter 375 Planning Group. (2018). First encounter 375 : 16-19 December 2017 : a documentary recording the commemoration held in Golden Bay/Mohua, New Zealand. [DVD]. Balloon Dog Production. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1108235554

Visit Sites associated with Abel Tasman

- Abel Tasman Monument

Located on a hill overlooking Tarakohe in Golden Bay / Mohua, this lookout monument was opened in 1942 to mark the 300th anniversary of Tasman’s encounter with Māori in the bay.

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/abel-tasman-national-park/abel-tasman-monument/an National Park. (retrieved May 4, 2022) - Abel Tasman National Park

New Zealand’s smallest national park (22,500ha), Abel Tasman National Park was opened in 1942 to mark the 300th anniversary of Abel Tasman’s visit to Golden Bay.

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/abel-tasman-national-park - Abel Tasman Statue

Located in the Abel Tasman carpark at Tāhunanui Beach, Nelson, this life-size statue of the Dutch explorer was sculpted by Anthony Stones in the United Kingdom and gifted to the region by Dutch immigrants. It was unveiled in 2000. - Golden Bay Museum

Learn more about Abel Tasman and his visit to Golden Bay / Mohua with displays and dioramas at the museum in Commercial Street, Tākaka.

http://goldenbaymuseum.org.nz/?s=abel+tasman

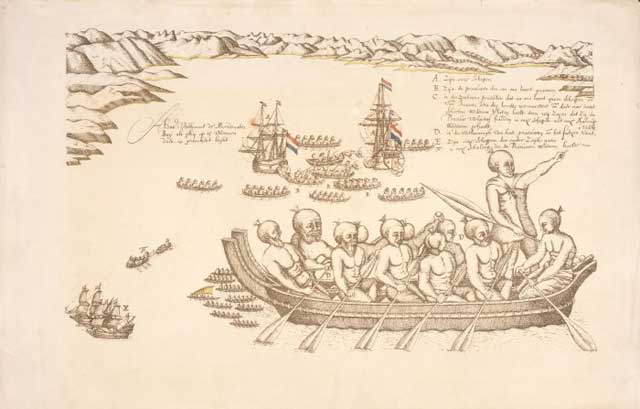

Gilsemans, Isaac: A view of the Murderers' Bay, as you are at anchor here in 15 fathom [1642], drawings and print collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, PUBL-0086-021

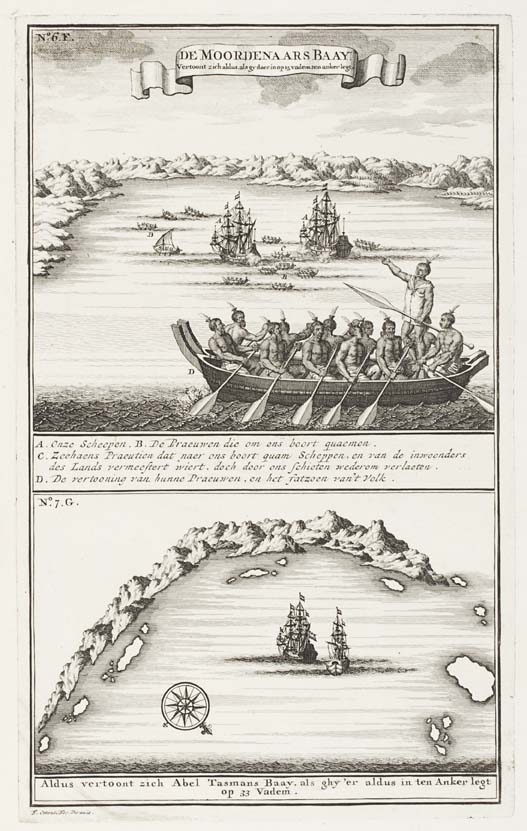

Gilsemans, Isaac: A view of the Murderers' Bay, as you are at anchor here in 15 fathom [1642], drawings and print collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, PUBL-0086-021 De Moordenaars Baay ; Aldus vertoont zich Abel Tasmans Baay, als ghy'er aldus in ten anker legt op 33 vademen, Engraving, Frederik Ottens (active 18th century), Nelson Provincial Museum: NPM2012.47

De Moordenaars Baay ; Aldus vertoont zich Abel Tasmans Baay, als ghy'er aldus in ten anker legt op 33 vademen, Engraving, Frederik Ottens (active 18th century), Nelson Provincial Museum: NPM2012.47 Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp (attrb) (c1594 – 1651). [Abel Janszoon Tasman]. Portrait of Abel Tasman, His Wife and Daughter c.1637 (part of). Colour photograph printed on textured canvas board. The original oil on canvas is held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra (Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK3. Pictures Collection. National Library of Australia), and reproduced by special arrangement with the National Library of Australia, Canberra. Nelson Provincial Museum: A5066.

Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp (attrb) (c1594 – 1651). [Abel Janszoon Tasman]. Portrait of Abel Tasman, His Wife and Daughter c.1637 (part of). Colour photograph printed on textured canvas board. The original oil on canvas is held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra (Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK3. Pictures Collection. National Library of Australia), and reproduced by special arrangement with the National Library of Australia, Canberra. Nelson Provincial Museum: A5066.