Ferdinand Hochstetter (1829-1884)

The father of New Zealand Geology - on the 150th anniversary of his survey of the Nelson region

Just how did a German geologist come to survey the Nelson region's mineral resources, gift a major mineral and fossil collection to the Nelson Institute and lay the foundation of what would become The Nelson Provincial Museum

The story of Ferdinand von Hochstetter is told in an exhibition marking the 150th anniversary of his mineral survey of the Nelson region at The Nelson Provincial Museum from May 9-September 18, 2009. This exhibition runs alongside a national touring exhibition called NZ Fossils Dead Precious!, which shows fossils as indicators and predictors of things like climate change, evolution, natural disasters and mineral deposits.

Christian Gottlieb Ferdinand [von] Hochstetter was 29 years old when he arrived in New Zealand, in December 1858, on board the frigate Novara, as the geologist for an Austrian global scientific expedition. Hochstetter, on behalf of the Colonial and Auckland Provincial governments assessed newly discovered coal seams at Drury to the south of Auckland. Given leave from the Novara, Hochstetter then undertook work for the Auckland Province, including mapping the 50 volcanoes around Auckland, before examining the southern part of the province, including the active Taupo Volcanic Zone.

In 1859 the Nelson Provincial Government invited Hochstetter, on the initiative of the Nelson Chamber of Commerce, to visit Nelson and make a report on the province's mineral wealth. At the time Nelson was considered to be the country's mineral province, following the discovery of chromite, coal, copper and gold, but apart from a gold rush in the Aorere Valley just two years earlier, mining had yet to prove successful. The Provincial Government was keen to obtain an independent scientific appraisal of the mineral resources, because mining was seen as vital to a province with limited land for farming.

Hochstetter arrived in Nelson on August 4, 1859, accompanied by his German friend, Julius Haast , who was in Auckland to assess emigration possibilities for Germans. Together they investigated the Aorere goldfield and the Pakawau coal seams, with Hochstetter producing sketches, watercolours and maps, something he did throughout his survey in Nelson.

The discovery of moa bones in caves at Aorere fascinated Hochstetter and, in return for a complete moa skeleton, which he shipped to Vienna, he arranged for a major collection of international minerals and fossils to go to the Nelson Institute, now The Nelson Provincial Museum. The museum still holds a number of items from the collection, although the bulk of it is now with GNS Science in Wellington.

Once Hochstetter and Haast finished their investigation of Golden Bay they moved to the eastern part of the province, examining the copper and chromite mines near Dun Mountain. The result probably was not what the Provincial Government wanted to hear. Hochstetter found that the rusty or dun weathering rock forming the mountain was largely made up of the mineral olivine, which he named dunite. He concluded there were no large deposits of copper and that it was doubtful if the more abundant chromite could be economically mined. [However, in 1862, the Dun Mountain Copper Mining Company opened the Dun Mountain Railway between the chromite mines and Port Nelson.]

As Hochstetter completed mapping the northern part of the province, Haast examined the Wairau and Awatere valleys.

Hochstetter was warmly received by the Nelson community: a dinner and ball were held in his honour when he was invited to lay the foundation stone of the new Nelson Institute and Museum building in Hardy Street on August 26 1859. The building opened in 1861 and remained until fire destroyed the library section in 1905.

Hochstetter was reported in the Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle as being honoured by the invitation to "lay the corner-stone of an edifice designed for the noble purposes of art and science - the Nelson Institute.....Certainly a cheerful and memorable epoch in the history and development of the young colony, when the enterprising pioneers, after the toils and labours of their settling down had succeeded - after their houses had been roofed over, and fields and meadows put in due order - now direct their attention also to the nobler purposes of life, to the nursing of the blossoms and fruits of our civilization, of art and science."1

The foundation stone can be found in the foyer of the Elma Turner Library http://www.nelson.govt.nz/assets/Leisure/Downloads/literary-trail-v2.pdf in Halifax Street.

On September 26, 500 people packed a public lecture Hochstetter gave about the province's geology. Nelson's love affair with Hochstetter appears to have been reciprocated. He was reported in the Nelson Examiner as saying: "On account of its beautiful site and its delightful climate, Nelson is justly considered one of the most pleasant places of sojourn in New Zealand. The impression made by the snug little cottages, surrounded by beautiful gardens, is an extremely cheerful one."2

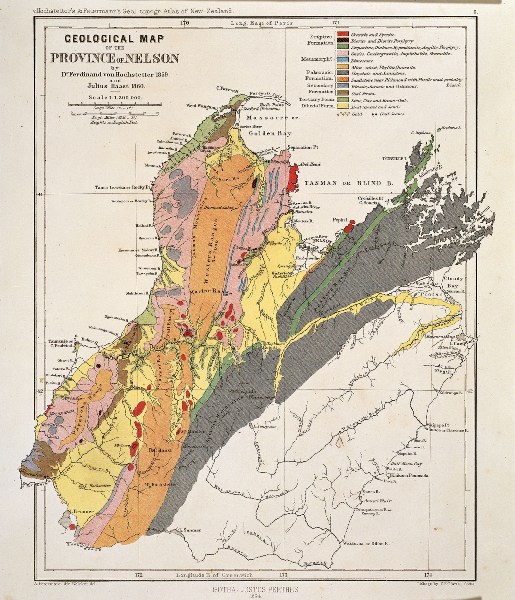

When Hochstetter left the province for Sydney in October 1859, on his way back home, Haast continued in Nelson and undertook an eight month survey of the western part of Nelson. Their combined efforts resulted in the first published geological map of the Nelson province, which, along with a geological map of Auckland, were the first of their kind in New Zealand.

Upon his return to Vienna, the man who became known as the father of New Zealand Geology, maintained contact with friends made in Nelson and continued to promote New Zealand in Europe through public lectures and various publications about New Zealand's geography, geology and natural history.

This article first appeared in issue 35 (2009) of Wild Tomato (additional editing has been provided by Mike Johnston)

Updated April 24, 2020

Story by: Karen Stade

Sources

- The Nelson Institute (1859, August 27) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle,p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18590827.2.8 - Lecture on the geology of the province of Nelson (1859, October 1), Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle 18(79), p.1

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18591001.2.23

Further Sources

Books

- Bade, J. (1993) The German connection: New Zealand and German speaking Europe in the nineteenth century. Auckland, N.Z. :Oxford University Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/30626781 - Carle, W. & Fleming, C.A. (1884; 1988) Carlé's biography of Ferdinand von Hochstetter / translated by C.A. Fleming ... [et al.]. [Lower Hutt, N.Z. : Geological Society of New Zealand]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/31873019 - Fleming, C.A. (1959) Dr. Hochstetter in Nelson : (extracts from the diary of Sir David Monro, 1813-17 [i.e. 1813-77]) [Wellington, N.Z. : C.A. Fleming, 1959]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174095431 - Fleming, C.A. (1960) Hochstetter centenary.Wellington, N.Z. : Royal Society of New Zealand

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174095462 - Haast, J. von ( 1884) In memoriam : Ferdinand Ritter von Hochstetter [Dunedin, N.Z.] : [J. Wilkie & Co.]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156747445 - Haast, H.F. (1948) The Life and Times of Sir Julius von Haast Wellington, N.Z

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4085605 - Heger, F. (1884) Ferdinand von Hochstetter Wien [Austria] : Eduard Hölzel.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/253391291 - Hochstetter, F. von (1859) Lecture by Dr. Ferdinand Hochstetter and presentation by the inhabitants of Nelson.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155659852 - Hochstetter, F. von (1863) Neu-Seeland. Cotta'scher Verlag [held Nelson Public Libraries]

- Hochstetter, F. von (1867) New Zealand : its physical geography, geology, and natural history : with special reference to the results of government expeditions in the provinces of Auckland and Nelson [translated from the German original, published in 1863, by Edward Sauter, ... with additions up to 1866 by the author]. J.G. Cotta [held Nelson Public Libraries]

- Hochstetter, F.von & Fleming, C.A. ( 1957) Geology of New Zealand : contribution to the geology of the provinces of Auckland and Nelson [Novara Expedition] [Auckland, N.Z. : Auckland Museum,] http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174104072

- Johnston, M. & Nolden, S. (2011) The travels of Hochstetter and Haast in New Zealand, 1858-1860. Nelson, N.Z. : Nikau Press

- Nolden, S. (2007) The letters of Ferdinand von Hochstetter to Julius von Haast : an annotated scholarly edition [thesis]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155820009 - Novara Expedition (1857-1859) Reise der Osterreichischen Fregatte Novara um die Erde in den Jahren 1857, 1858, 1859 unter den Befehlen des Commodore B. von Wullerstorf-Urbair. Geologischer Theil. [Erster Band; Zweiter Band] (1864; 1867) Aus der kaiserlich-koniglichen Hof-und Staatsdruckerei [held Nelson Public Libraries]

Newspapers

- Collett, G. (2009, August 22) A natural superstar. The Nelson Mail, 15

- Cowan, J (1937) Two pioneers of science - Dr Hochstetter and Sir Julius von Haast - their travels and explorations 1870-1943 Enzed junior, 4:pp. .298,303 (supplement to the Auckland Star)

- Dr. Ferdinand von Hochstetter. (Obituary) (1884) Geological magazine. 21 : p. 526-528

- Dr Hochstetter in Nelson (1959) New Zealand journal of geology and geophysics, 2(5) : p. 954-963

- Ferdinand Hochstetter in New Zealand (1992) New Zealand Map Society Journal n.6:p.11-18

- Ferdinand von Hochstetter (Obituary) (1885) Quarterly journal of the Geological Society of London. 41: p. 45

- Hochstetter - father of New Zealand geology (1971) New Zealand's heritage, v. 3. Sydney: Hamlyn Paul, pp.707-711

- Hochstetter - a pioneer of New Zealand geology (1988) Historic Places in New Zealand, .21, p.15-17

- Hochstetter Centenary, 1859-1959 (1959) Newsletter / Geological Society of New Zealand, 7, p.9-11

- Hochstetter - father of New Zealand geology (1971) New Zealand's nature heritage. 2(26), p. 706-711

- Hochstetter gets his due (2011) The Nelson Mail, July 16, p.14

- The Hochstetter-Heaphy controversy, or: Whose map was it? (2002) Newsletter / Historical Studies Group, Geological Society of New Zealand, 25, p.31-40

- The Hochstetter-Heaphy controversy : some further information (2003) Newsletter / Historical Studies Group, Geological Society of New Zealand, 27, p. 33-40

- Hochstetter's collection comes to library (2008, September 24) Auckland city harbour news, p 14

- Kermode, L.(1992) Hochstetter New Zealand Map Society Journal, .6:p.11-18

Websites

- Ferdinand von Hochstetter: father of New Zealand geology (1829-1884). Retrieved from Auckland City Libraries, 23 July 2009:

http://www.aucklandcity.govt.nz/dbtw-wpd/virt-exhib/hochstetter/index.html - Fleming, C. A.(2007) 'Hochstetter, Christian Gottlieb Ferdinand von 1829 - 1884'. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1h30/hochstetter-christian-gottlieb-ferdinand-von - Hochsetter's. F.A. (1867) New Zealand its physical geography, geology and natural history with special reference to the results of government expeditions in the provinces of Auckland and Nelson. Available from Early New Zealand Books Online:

http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document.php?action=null&wid=433 - Hochstetter. Retrieved from Wikipedia, 23 July 2009:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hochstetter - Hochstetter, Dr Ferdinand Ritter Von (2007) from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966. Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand:

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/hochstetter-dr-ferdinand-ritter-von/1 - Lecture on the geology of the province of Nelson (1859, October 1), Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle 18(79), p.1

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18591001.2.23 - Maling, Peter B (2007) . 'Haast, Johann Franz Julius von 1822 - 1887'. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/dnzb/Essay_Body.asp?PersonEssay=1H1&QuickSearch=true - The Nelson Institute (1859, August 27) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle,p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18590827.2.8 - Public dinner to Dr Ferdinand Hochstetter (1859, September 7) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, 18(72), 3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=NENZC18590907.2.11

Maps

- Ferdinand Hochstetter : exploratory journeys (1988) audio cassette [Series of two talks presented on Radio New Zealand 28 February and 3 March 1988] Wellington : Radio New Zealand