Murchison and the Buller or Kawatiri

Explore the deep connection between Murchison and the Kawatiri, or Buller River, its history, significance to Māori and the wider community, and the impact of natural disasters like floods and earthquakes, gold mining, and the construction of the Buller Swing Bridge.

The story of Murchison is inextricably entwined with that of the Kawatiri or Buller River and its tributaries. The mighty awa or river begins its 177 km journey to the West Coast from its source, Lake Rotoiti in the Nelson Lakes National Park.1 It finds its westerly path near Murchison, which is located on the Four River Plain at the confluence of the Buller, Mātakitaki, Mangles and Mātiri Rivers.2 The Māori name for the River is Kawatiri, meaning swift and deep and is associated with the Ngāti Rārua chief Kawatiri, who watched over the trail between Ngai Tahu and Ngāti Rārua lands. The Europeans called it the Buller, after Charles Buller, a director of the New Zealand Company.

Flooding

Many ‘record’ floods have caused loss of life, devastation and disruption in the Murchison District with a major tributary, the Mātakitaki River, causing the most flooding problems in recent times.3

The 'normal' flow of the upper Buller River at the Longford data recorder north of Murchison is 56 cumecs.3 By the time the Buller reaches the bottom of the Four Rivers Plain, normal flow is approximately 110 cumecs.3 In October 1998 a flood of 1380 cumecs was recorded at the Longford recorder4 and the upper Buller River reached 6.2 metres, the highest level since recording began in 1964.5

In 1878, the Buller and Mātakitaki Rivers both became raging torrents and cut into the land on which Murchison, then known as Hampden was being built. Several buildings had to be abandoned and local identity and hotelier, George Moonlight decided to rebuild his Commercial Hotel away from the river.6

Lyell was isolated, with roads either side of the gold mining settlement blocked and impassable following a disastrous flood in 1878. ‘There was no Flour in town, there has been no Beef in the place for a week, and the last Pig was killed after eating the last spud....are the people to starve through the neglect of the Buller County…?’ 7

Ten years later, in March/April 1888, a succession of floods in the Buller and Inangahua Rivers destroyed the hard work of the settlers with fences and farmland, sheep, apples and crops all swept down the river.8

In 1926 the Buller cut into the Four River Plain: much of the road was taken, as well as pasture and stock. The access road from Longford completely disappeared and new road had to be constructed. 9

Drownings

The Buller has claimed many lives. In October 1893, Mrs O’Rorke and Miss McInroe were crossing the Buller when the horse broke loose from the trap. A bypasser went to their aid and, as they were putting a child into his dray, the buggy turned over and both women were thrown into the current, carried away and drowned. 10

In 1941, a brother and sister, William and Dulcie Borkin were swimming with a friend in a swimming hole near Murchison when Miss Borkin got into trouble. Her brother went to help but they both drowned.11

Gold

The Grey River Argus reported in 1910 that three auriferous (gold bearing) rivers and five auriferous creeks ran into the Buller River within a few miles of Murchison. The junction of the Mātakitiki and Buller Rivers at Murchison had been worked since the 1880s, with payable gold and some rich patches struck.12

George Moonlight was known for making large gold discoveries throughout the South Island and then leaving them for other miners. He and his wife Elizabeth bought the Commercial Hotel, around which Murchison grew.13

Māori prospectors were the first to obtain gold from the Lyell region and, by 1863, about 100 miners had set up camp. There was a township with hotels and a National Bank at Lyell until the early 20th Century.14

The earthquake

On 17 June 1929, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake, centred in the Lyell Range west of Murchison, was felt from Auckland to Bluff. 15 A huge slip blocked the Mātakitaki River south of Murchison and there was a fear that water might break through the dam flooding Murchison and even Westport. Most people had left town by the time the water was released naturally. 16

The swing bridge

Rex Smith of Murchison has lived by the river for 63 of his 83 years and has worked in construction gangs along the Buller and its tributaries. One of the more memorable projects was the construction of New Zealand’s longest swing bridge.

“There had been an old swing bridge across the river there for a long time which was mainly used by miners, farmers and hunters. A man had bought the mining rights and wanted access to process the gold. In 1974 I was involved in building a new swing bridge which was made up of aluminium panels 6ft by 3 ft wide. It was a challenging project with the river roaring below. It hadn’t been up long when a big flood ripped out the large panels leaving the abutments and ropes,” he said. The Buller Swing Bridge was rebuilt immediately and still stands, or swings, today as a tourist attraction 14 kilometres west of Murchison.17

The Kawatiri and its tributaries - a place of significance for Māori.18

The Kawatiri River or Awa and its tributaries have cultural significance for Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Rārua and Ngati Toa Rangatira. For each iwi, the Awa was an important source of mahinga kai, with its fish such as kokopu, eels, inanga, kahawai, kekewai and koura and birds such as kaka, kereru, kakapo, kiwi, kakapo and weka, and it was an important route in a network of pathways. For Ngāti Rārua it was an important part of the greenstone trail between Te Tau Ihu and Te Tai Poutini.

Ngāti Apa relate stories of Takapau, kaitiaki of the gardens at Kawatiri, Te Rato (also known as Te Kotuku - the White Heron), Te Whare Kiore (who was killed there during the northern invasions), and the high-born woman Mata Nohinohi, mother of Mahuika and famous guide Kehu. Ngāti Apa stayed in the area after the taua or war party invasion of northern tribes, and led by Mahuika, they reoccupied a kāinga on the river in the 1840's.

For Ngāti Toa, one of the northern tribes which expanded their South Island interests after the iwi conflicts of 1829-32, the Kawatiri was an important route to more remote goldfields, where they developed innovative mining methods. Hohepa Tamaihengia of Ngāti Toa Rangatira was a successful miner on the Buller goldfields. In the hope of securing a better gold price he built a beautifully modelled whale boat, which was about 30 feet long, at the Quartz Ranges, which his party sailed down the Buller River and on to Wellington.19

2014.

Updated, March 13, 2025

Story by: Joy Stephens

Sources

- Buller River. From An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966.Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (updated 2009).

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/buller-river - Murchison. ( 2014, February 11). In Wikipedia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murchison,_New_Zealand - Martin Doyle [hydrologist, Tasman District Council] (Personal communication, December 2013).

- The West Coast Regional Council. River levels and rainfall. Buller River at Te Kuha.

- NIWA. New Zealand Historic weather events catalogue. October 1988 Western New Zealand flooding.

- Brown, M. (1976) Difficult Country: An Informal History of Murchison. Murchison Historical and Museum Society Inc., p 73.

- Untitled (1878, July 26) Grey River Argus, p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=GRA18780726.2.7 - Lyell District (1888, April 9) Inangahua Times, p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=IT18880409.2.7 - Brown, p. 199.

- Sad Fatality (1893, October 31) Oamaru Mail, p. 1.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=OAM18931031.2.4 - River tragedy (1941, January 6) Evening Post, p. 9.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=EP19410106.2.67 - In the Murchison District (1910, April 23) Grey River Argus, p. 1.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=GRA19100423.2.5.1 - Stephens, J. (2011) George Fairweather Moonlight. The Prow.

https://www.theprow.org.nz/people/george-fairweather-moonlight - Russell, S. (2011) Lyell. The Prow.

https://www.theprow.org.nz/yourstory/Lyell - Stephens, J. (2008) Murchison Earthquake. The Prow.

http://www.theprow.org.nz/events/the-murchison-earthquake - Flood Risk (1929, June 20) Auckland Star, p. 8.

- Rex Smith. (Personal communication, January 2014).

- Te Tau Ihu Statutory Acknowledgements 2014, Nelson City Council, Tasman District Council, Marlborough District Council. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE45094455

- Mitchell, H.& J. (2008). Koura - Māori and Gold. The Prow.

http://www.theprow.org.nz/maori/maori-and-gold

Further Sources

Books

- Barclay, A. (2013). The moonlight legacy. Arch Barclay: Nelson, N.Z.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/946519076 - Brown, M. (1976). Difficult Country: An Informal History of Murchison. Murchison Historical and Museum Society Inc.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/3241265 - Latham, D. (1992). The golden reefs: An account of the great days of quartz-mining at Reefton, Waiuta & the Lyell. Nikau Press: Nelson, N.Z.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/828594532 - Young, D., & Young, A. (2013). Rivers: New Zealand's shared legacy. Random House: Auckland, N.Z.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868149045

Newspapers

- Brown, M. C. (1988, December). The first bridge over the Buller. Murchison District Historical and Museum Society Journal. p.9.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/813642426 - Grzelewski, D. (1997, October). Buller- the mighty river. New Zealand Geographic

https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/buller-the-mighty-river/ - Peacock, A. (1988, December). The Buller River flood, 1926. Murchison District Historical and Museum Society Journal. pp.6-8.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/813642426

Newspaper articles from Papers Past

- Flood risk (1929, June 20) Auckland Star, p.8

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=AS19290620.2.86 - Loss of life: much damage to property (1905, June 26) Star, p.3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TS19050626.2.36.1 - Old settler missing. (1900, May 10) Colonist, p.2

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TC19000510.2.27.26 - On the new west coast road (1930, November 10) Evening Post, p.7

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=EP19301110.2.32.6 - Post Office reports (1929, June 20) Evening Post, p. 14

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=EP19290620.2.106.14 - River blockages (1929, June 20) Evening Post, p.14

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=EP19290620.2.106.12

Websites

- Buller River. From An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (updated 2009)

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/buller-river - Buller River. NZfishing.com.

https://nzfishing.com/nelson-marlborough/where-to-fish/buller-river/ - General history of the Buller Gorge. Buller Gorge Swingbridge.

http://www.bullergorge.co.nz/generalhistory.html - Buller Kawatiri Fresh Water Management Unit (FMU). Tasman District Council.

https://www.tasman.govt.nz/my-region/environment/environmental-management/water/water-management/freshwater-management-units-2/buller-kawatiri-fmu

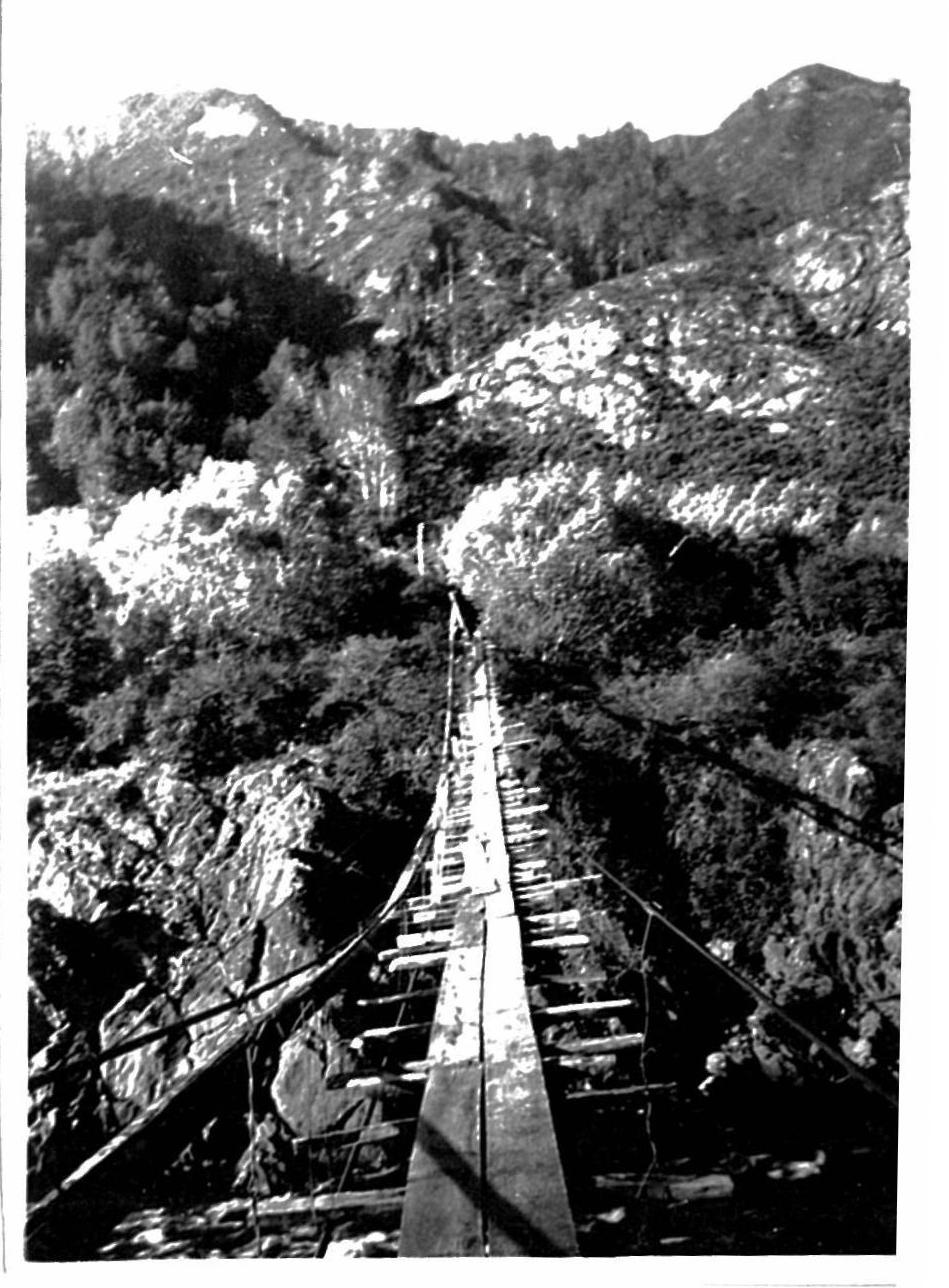

Buller Bridge 1938. Photo courtesy Rex Smith.

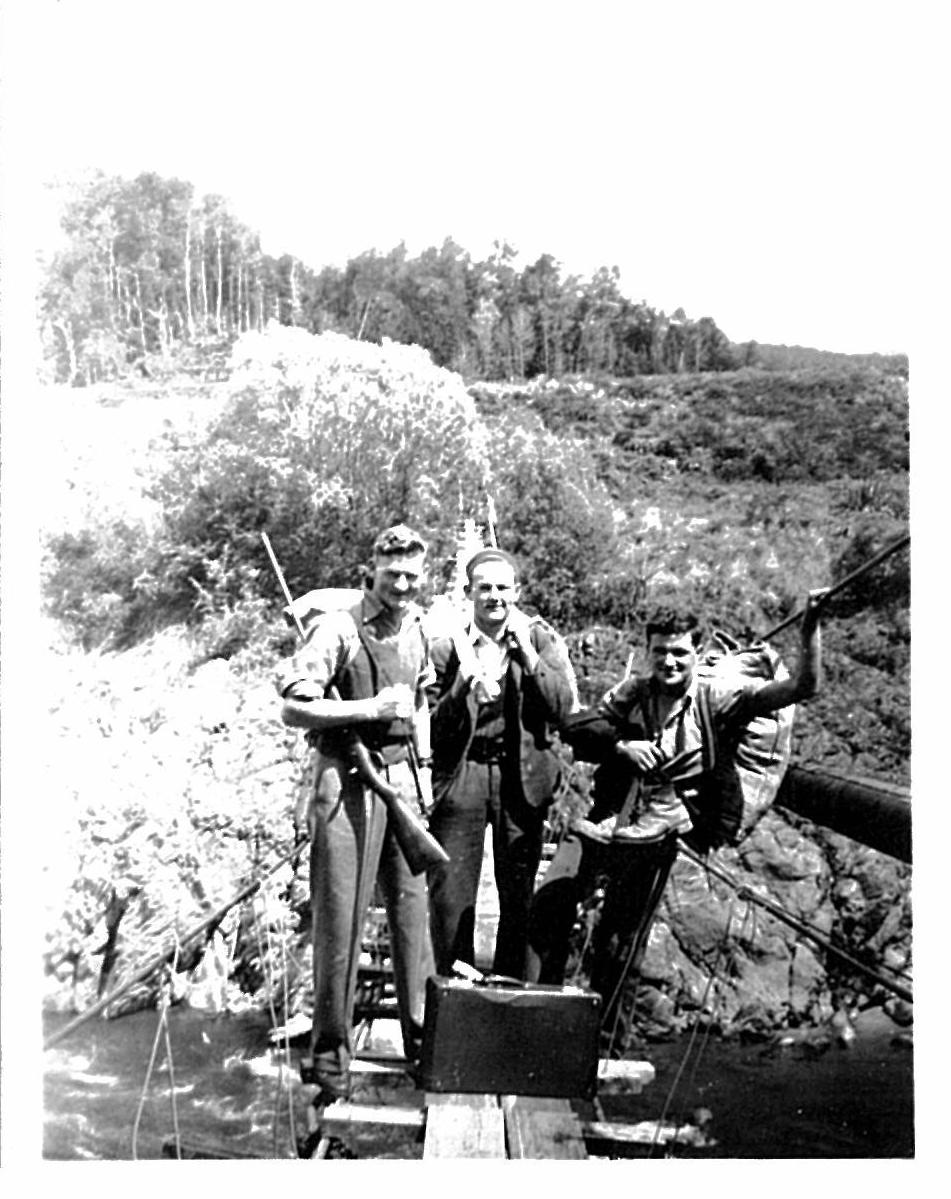

Buller Bridge 1938. Photo courtesy Rex Smith. Buller Bridge, 1938, with deer hunters Maurice Smith, Max and Ross Curtis. Photo courtesy Rex Smith

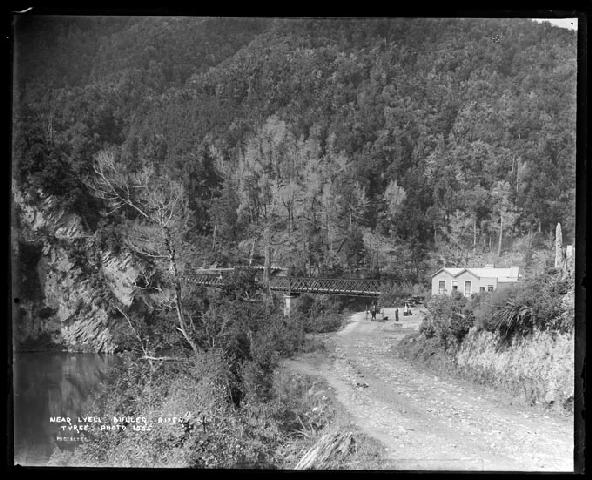

Buller Bridge, 1938, with deer hunters Maurice Smith, Max and Ross Curtis. Photo courtesy Rex Smith Near Lyell, Buller River. Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection: 181955

Near Lyell, Buller River. Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection: 181955 Matakitaki bridge, damaged by the Murchison earthquake, 1929 Alexander Turnbull Library: 1/1-010104-G.

Matakitaki bridge, damaged by the Murchison earthquake, 1929 Alexander Turnbull Library: 1/1-010104-G.