Picton Hospitals

From 1865 to 1989 Picton had its own hospital.

The first Picton hospital was built on the hill overlooking Waikawa Road and the Lagoon in 1865. A character called 'Ned the Bellman' (Edward Allen Davis) died earlier that year, leaving a £200 legacy for building a hospital in the town. Dr Julius Decimus Tripe was appointed Provincial surgeon of Marlborough shortly afterwards, and the new Marlborough Provincial Hospital was built by Avery Bros builders immediately. Poor Ned the Bellman, humble and forgotten benefactor of Marlborough’s Provincial Hospital, had provided almost half the cost of the building, but was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in Picton cemetery.

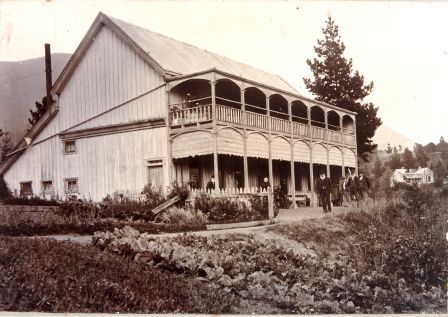

The furnishings of the first Marlborough Provincial Hospital were of the most primitive description: wooden stretchers with sacking, the mattresses were palliasses stuffed with straw, its pillows flour bags filled with chaff. An upper storey balcony was added a few years later.

In 1872 a reporter from the Marlborough Express visited the hospital and gave his approval: “Our inspection proved that the rooms and floors are kept beautifully neat and clean and the food we saw in preparation for the daily meal was all that could be desired. The site of the Hospital is particularly pleasant and healthy, having a full view of the harbour and the Waikawa Road.” However with the snobbery of the day he added that some of the patients “should come under another class, perhaps were there a House of Refuge provided.” It seems that a number of indigent old men resided in the hospital over a period of years.

Administration of this hospital was assumed by Picton Council in 1876, and Picton District Health Board took over in 1885. Finally, in 1930, Marlborough District Hospital Board was formed, amalgamating Picton, Havelock and Wairau Hospital boards.

By the end of the century it was necessary to replace the hospital. When seeking a Government grant, the Secretary wrote: “The present building is over 35 years old, and built of white pine, that is full of dry rot. The upstairs flooring breaks under tread of a man, and the whole structure is shaking to pieces. It had been patched again and again, and the Board found it impossible to keep it any longer in habitable repair.” In view of the above facts, and also because the number of patients was increasing owing to the expansion of the District and the establishment of the new Meat Freezing Industry, a new hospital was a necessity.

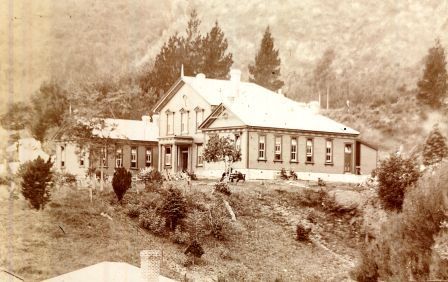

During construction of the new hospital, it was decided to complete each wing before removal of the old building, so that patients would not have to be removed to other premises. In 1902 the second Picton Hospital was opened, Dr William Edward Redman replacing Dr H.A.H. Claridge as Medical Officer later the same year. The operating room was based on that at Dunedin Hospital, but on a smaller scale.

Gradually new additions were made to this hospital in keeping with the times. Shelter sheds were built in the hospital grounds for tuberculosis patients in 1907, with the idea that fresh air aided their recovery, but also to isolate them from other patients. A few years later in 1911, a new ward was built for infectious diseases – this became known as the ‘Fever Ward’, and the building now stands in the Powerhouse Reserve (now Auckland Street Reserve) in Wairau Road. The Maternity Annex was added in 1913, the first of its kind in New Zealand.

A third Picton Hospital, with 28 beds, was opened in 1953 – this later became the Seaview Home. The Maternity Annex was closed in 1975 and changed for general and convalescent use, and in 1989 Picton Hospital was finally closed after much discussion and protest.

Joan Barrett [a nurse who worked in the hospital in the pre-antibiotic days before World War II] recalls:

“Nursing in those days – can you imagine what it was like? There were all those awful polio epidemics – measles. No drugs, nothing. I remember the diphtheria, we had a bad outbreak of diphtheria, and it was the first time when the anti-dip. injections came in. All the staff had to have it. We nearly lost some of our nurses.

Picton had two little TB shelters. We had a Māori boy and another lady in the two shelters, and you’d have to go out, wet or fine, every hour. Go round and see if they were all right. There was netting all around the top, and the glass doors on three sides, but there was always the air coming in through the netting there. Nobody ever got up – they were all bed-bathed and that sort of thing. Then of course when it was wet it was a nuisance. Concrete paths around them, but it was dripping in between. You did everything, there. You did the cleaning, tidied their rooms up. Patients were there for years, some of them.”

She also remembered the primitive operating facilities: “The doctors and staff came through and operated in the old theatre in Picton. Poky little place, it was, but they did the job, just the same. Very crude. There was a big old black stove, and the big boilers you boiled up on the old black ranges. I can imagine the nurses today!”

Condensed from stories written for the Seaport News in 2010 by Loreen Brehaut

Updated May 2020

Story by: Loreen Brehaut

Sources

- Picton Museum archive

Further Sources

Websites

- How are our hospitals administered? (1882, March 27) Marlborough Express, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18820327.2.8 - The hospital district (1888, June 22) Marlborough Express, p. 3

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18880622.2.31 - The Picton Hospital District (1891, September 2) Marlborough Express, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18910902.2.13 - The two hospitals (1891, September 2) Marlborough Express, p. 2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18910902.2.9 - Dr Macgregors report (1891, September 10) Marlborough Express, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18910910.2.11 - Hospital Amalgamation (1897, November 5) Marlborough Express, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18971105.2.8 - Amalgamation of Picton and Wairau Hospital Districts (1897, November 16) Marlborough Express, p. 2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18971116.2.26

Maps

- Picton Museum has a large display of artefacts from the Picton Hospitals. A photo exhibition of these is on the website of the Marlborough Museum :

https://virtualexhibit.marlboroughmuseum.org.nz/picton/vewebsite8/exhibit2/vexmain2.html