Dumont d'Urville's Tasman Bay Odyssey

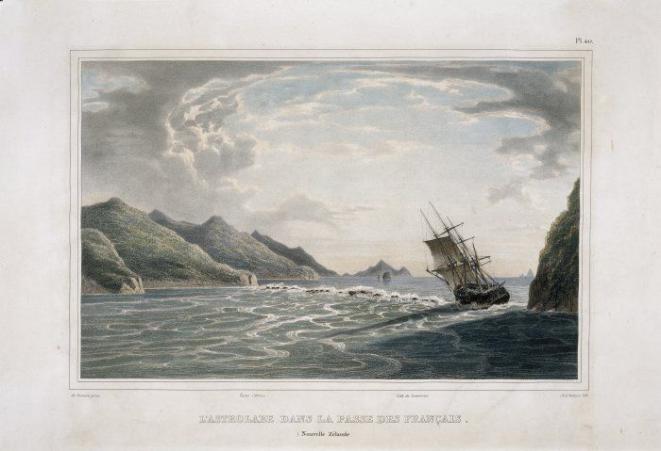

DUrville and the Astrolabe faced terrible weather conditions as they crossed the narrow passage between Tasman Bay and Admiralty Bay on 22 January 1827

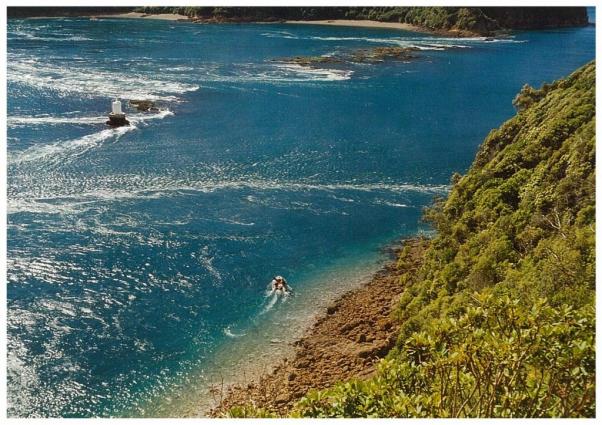

On a windless day, the view of Tasman Bay from the ridge leading to French Pass seems enchanting but harmless. The battalions of rocks fringing the southern tip of D'Urville Island, and even the Beef Barrels, in the middle of Current Basin, form dark patterns in the bright water, perfectly visible and unthreatening. But when it blows hard nor'west, the situation changes. The rocks are hidden by spray, and the waves crash furiously against the cliffs on either side. In those conditions, even a powerful launch may find itself obliged to spend hours steaming into the wind, without any hope of making headway, just to save itself from being swept ashore.

This was the kind of weather that beset d'Urville and his crew when they found themselves confronting the narrow passage between Tasman Bay and Admiralty Bay, on 22 January 1827. They had to decide whether to try and negotiate it or turn back.

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville was a highly trained and very experienced French naval officer of 36. He now captained the same ship, renamed the Astrolabe, that he had been second in command of on his previous voyage to New Zealand. By the time he and his crew reached Current Basin, they had been at sea for nine months, travelling from Toulon in the Mediterranean down the west coast of Africa, across the southern Indian Ocean and the dangerous Great Australian Bight and, after a brief call at Port Jackson, now Sydney, had encountered appalling weather in the Tasman Sea.

Their ship was a three masted square rigged naval corvette, about 31 metres long, with a beam of 8.5 metres (the figures vary) and weighing 380 tons, or under two thirds the size of the ship that brought the first main group of settlers to Nelson, the Martha Ridgeway. Small though she was, she had set out with a crew of some 79 officers and men, including a number of scientists and an artist, Louis-Auguste de Sainson. She also, according to d'Urville's biographer, John Dunmore, carried a vast cargo of food supplies, including 400 kilograms of dried meat, 3,600 kilograms of vegetables, such as dried peas and beans, ship's biscuit, sugar, and chocolate, as well as wine and spirits. Lastly, she was equipped with a small number of six-pounder guns.

The crew numbers did diminish during the course of the voyage. Three jumped ship, 11 died, mostly from dysentry, and 15 more had to be left behind at various ports of call, again for reasons of illness. It all suggests that conditions on board were difficult. How relieved all hands must have been when they finally rounded Cape Farewell, after 20,000 kilometres or so, and finally found safe anchorage in the Astrolabe roadstead. While there, de Sainson painted a delightful picture of the men washing their clothes in a leisurely way in Astrolabe Creek, and sunning themselves on the sands.1

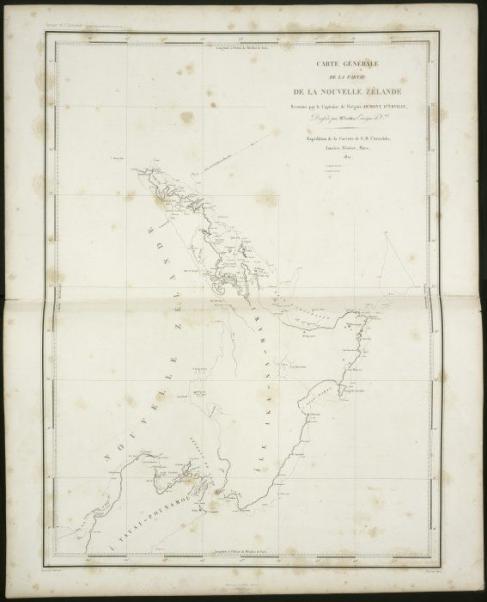

The Astrolabe rounded Farewell Spit on 14 January 1827. Everyone was fully aware that they were sailing in uncharted waters. The local Māori would have known the coastline for many miles around, and whalers and sealers had been pottering about for nearly half a century - the first shore based whaling station was established in the Tory Channel, on the other side of the island, by John Guard at the end of the same year. But none of these had left records. Cook himself had sailed right across the mouth of Tasman Bay from Cape Farewell to Stephens Island, but in weather so thick he could only sketch the possible outlines of what he called Blind Bay. D"Urville, who was familiar with Cook's work, was under instructions to fill in the inevitable gaps.

His officers and the scientists on board immediately began work. The Astrolabe anchored about 10 kilometres from Separation Point, and the next day d'Urville dropped Guilbert and some of his colleagues on the point itself. They worked there until about 11.30, when a suitable breeze allowed the ship to continue. D'Urville then followed the coast as far as the Moutere Bluff, which he named Cap Blanc [Cape White]. On the way he noticed a Māori village, perhaps near Marahau, a magnificent stand of native pines [podocarps] somewhere about Riwaka, and a ‘narrow channel' that must have been the Motueka river. All the way his crew were taking soundings, which are noted on a chart held in the Alexander Turnbull Library.

The ship moved some distance out to sea to find a suitable anchorage. The wind dropped, and it was a beautiful night. Next day the ship continued to follow the coastline to the far side of the bay, where the shore rose to form lofty bluffs, perhaps off the Glen or Cable Bay. A group of Māori paddled out to meet them, and pointed out their village on the shore, perhaps somewhere near where Nelson now stands.2 As there was no safe anchorage in the area, d'Urville backtracked to what is now the Astrolabe roadstead, which he had seen on the way in, and there the ship stayed for the next few days.

The crew worked there replenishing their supplies of wood and water, and fraternising and trading with the local Māori. D'Urville had a working knowledge of Māori, which he had picked up on his earlier voyage, when a missionary and a couple of Māori had travelled on his ship from Sydney, and also during his stay in the Bay of Islands.3 He was even able to recognise dialectal differences. The ship's surgeon, Gaimard, was also doing his best to learn Māori. The Māori they encountered were very friendly, but on edge, because the marauding tribes from the North Island, led by Te Rauparaha were already very close, and they rather hoped that d'Urville could help them, perhaps by killing and eating a few of the enemy. 4

At the same time, the scientists on board, including d'Urville, himself a distinguished botanist, explored the flora and fauna of the area, which de Sainson also sketched. His paintings of what he saw, the landscapes, the flora and fauna, the Māori, their dress, their equipment, their houses, and their mode of life, many of which are held in the Alexander Turnbull Library, are a remarkable record of the area at that early time.

On 22 January d'Urville and his crew set out in light winds from Astrolabe ‘with everyone in good health, the ship completely reprovisioned, and the collections enriched with an incredible number of new finds,' wrote d'Urville proudly. They sailed across Tasman Bay to explore a couple of breaks they could see in the coast on the eastern side. The first, possibly Delaware Bay, or else the mouth of the Wangamoa river, they found too shallow to be of interest, and they continued to the next, which they reached just on dusk. Although it seemed to offer shelter, d'Urville prudently decided not to go in in the dark, and stood out a little way to sea. However, the wind dropped entirely, and the heavy seas drove them relentlessly towards the steep rocky headland on the south-western side of what d'Urville was to name Baie de Croisilles, after his mother's family. The danger was extreme, and the crew spent a nerve-wracking night working with sweep oars to keep the vessel clear. The wind changed about daylight, and the exhausted men could carry on to the north. Not surprisingly d'Urville named the headland Cap des Soucis, Cape Anxiety.

They arrived off the entrance to French Pass on January 23, intending to sail straight through, but the lookout noticed rocks ahead. They hove to immediately, and ran out an anchor. Then the wind freshened, and the seas rose. A couple of officers set out in rowboats to explore, and their men came back worn out with rowing against the current. Overnight the norwest wind worsened, until the situation became critical and they were facing shipwreck. They put out another anchor, but one cable snapped, and the second anchor only just held, as one fluke had been damaged by rocks. Finally the weather abated, to their vast relief.

They then tried to cross at the western end, carrying only small amount of sail, but once again they encountered rocks, and the current caught them, sweeping them around in circles several times and right back across Current Basin, so close to Cross Point (named by them Cap des Tourbillons or Cape Whirlpools) that they fully expected to hit it. The ship's boat managed to get down an anchor in the nick of time. At that point d'Urville put his scientists and de Sainson ashore, partly to get them out of the way while the crew tidied up a tangled mess of ropes and cables, and partly to calm down the crew themselves, by seeming to be carrying on as usual. By 4 o'clock, after twelve hours of exhausting effort, they were at last able to stop for a meal, and d'Urville, who had previously called his men ‘pusillanimous' was pleased with the way they had showed what they were capable of in a time of crisis.

The day however was not over. In the evening d'Urville himself set out with Guilbert to explore the pass. It took six rowers to cope with the current even on its outer edge. Again a squally norwesterly sprang up at night, accompanied by heavy rain. Guilbert spent the whole of the next day, 25 January, charting the pass, and d'Urville too set out again at low tide. The sea had dropped, but the current was still strong, and swept him through to Admiralty Bay. Fortunately he was able to return at what is known as slack water, when the tide is on the turn, and the current ceases to run for about a quarter of an hour. It allowed him to see that the only practicable passage was right under the headland on the eastern side, and measured between 30 to 40 ‘toises' or 60 to 80 metres. At slack tide and with a favourable wind, it could be managed.

The alternative was to try and circumnavigate what was to be known as D'Urville Island, which he recognised would be a ‘long and disagreeable' journey. In fact, in norwest weather, it would have been downright dangerous. There is no shelter in such weather anywhere between Croisilles Harbour and French Pass, nor along the western coast of the island as far as Greville Harbour. Even if the ship got that far, or further on to Otu or Port Hardy, there was a serious risk of its being bottled up for days until the seas went down. The Astrolabe was in a real pickle.

That night the norwest rose again, accompanied by a thunderstorm and heavy rain. But by morning it turned west souwest, and d'Urville decided to try, only to have his ship swept back once again hard up against what he called that ‘blasted Cross Point' (le malheureux Cap des Tourbillons). After 13 hours of backbreaking work, they were no further ahead. And at night again it blew strong Norwest.

Still, they spent the next day manoeuvring the ship into a favourable position so that they could set sail immediately the wind was right again. D'Urville himself put in a little time botanising on the island side of the basin. And again the ‘eternal westerly' blew all night.

On the 28th the situation looked better. At daylight, D'Urville battled his way up through the dense scrub to the top of the hill overlooking the pass, and had a moment of extreme doubt. If he failed, the ship and all his crew might well perish. But he decided to risk it. The wind was again west souwest, they ran up the sails, but just as they entered the pass, it dropped again. Though they fought to keep close to the headland on the right of the channel, the current swept them left onto the reef and they scraped it twice. The ship keeled over briefly, but then the wind picked up, and blew them on, only slightly damaged, into the quieter waters of Admiralty Bay. Care and cussedness had got them through.

2009

Updated: April 2020

Story by: Nola Leov

Sources

- Mitchell, H & J (2004) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, vol I The people and the land. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatu Incorporation, p. 212,

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Mitchell, 221.

- Dunmore, J. (2007) From Venus to Antarctica: The Life of Dumont d'Urville. Auckland, N.Z. : Exisle Publishing, p.71

- Mitchell, 208-222

Further Sources

Books

- Baldwin, O. (1979) Story of New Zealand's French Pass and d'Urville Island, Plimmerton, N.Z. :Fields Publishing House, book 1, ch. 3

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8947642 - Beaglehole, J. (1974) The life of Captain James Cook London : A. and C. Black

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/3121392 - Brailsford, B. (1997) The Tattooed Land, 2nd ed., Hamilton, N.Z.: Stoneprint Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50511324 - Dunmore, J. (2007) From Venus to Antarctica: The Life of Dumont d'Urville. Auckland, N.Z. : Exisle Publishing

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156759417 - Duyker, E. (2014) Dumont D'Urville: explorer and polymath. [Otago, New Zealand] : Otago [University Press]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/879528655 - Maclntyre, D., Field, M. & Quinn, C. (1983), Cook's Wild Strait, Wellington, N.Z : Reed, 1983

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/11238884 - Mitchell, H & J (2004) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, vol I The people and the land.. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatu Incorporation

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Morton, H. (1982) The Whale's Wake. Honolulu : University of Hawaii Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9136131 - Wright, O.(ed) (1950) New Zealand, 1826-1827, from the French of Dumont d'Urville : an English translation of the Voyage de l'Astrolabe in New Zealand waters. Wellington, N.Z.: Printed by the Wingfield Press for Olive Wright. [Alexander Turnbull Library holds the original text with related maps. ]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154481449

Newspapers

-

Neal, T. (2008, May 3) Our French connection. The Nelson Mail, 17

Websites

- Admiral Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville. References in the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre:

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/name-207864.html - D'Urville, D. (1950) New Zealand 1826-1827: From the French of Dumont D'Urville. [New Zealand]: Wingfield Press. Retrieved from NZETC:

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WriNewZ.html - Jules Dumont d'Urville. Retrieved 15 October 2009 from Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Dumont_d'Urville - Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville: Journeys of Enlightenment. Retrieved 10 October 2009. from WA Museum http://www.museum.wa.gov.au/exhibitions/journeys/The_Explorers/d_Urville.html

- Pacific voyages: The voyages of the Astrolabe. Retrieved 16th October, 2009 from University of Canterbury:

http://www.canterbury.ac.nz/voyages/astrolabe/ - Simpson, M.(2007)Dumont d'Urville, Jules Sébastien César 1790 - 1842. In Dictionary of New Zealand Biography:

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1d19/dumont-durville-jules-sebastien-cesar - Smith, P (1907) Art. XL.-Captain Dumont D'Urville's Exploration of Tasman Bay in 1827. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1868-1961, 40, p. 416

http://rsnz.natlib.govt.nz/volume/rsnz_40/rsnz_40_00_006600.html

Maps

Maps

- Coastal Photomaps, Marlborough Sounds. (1987) Nelson [N.Z.] : Aerial Surveys Ltd

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154369186 - The Geographic Atlas of New Zealand (2005) Nelson, N.Z. : Craig Potton Pub Craig Potton, pp. 130,131,132. [Guilbert's charts - originials held in Alexander Turnbull Library]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62349034