Port Nelson

Nelson Haven has undergone remarkable change over the last 150 years. From its humble beginnings as a snapper spawning ground to the full scale international port here today, the Haven has always played an essential role in the local community.

Nelson Haven has undergone remarkable change over the last 150 years. From its humble beginnings as a snapper spawning ground to the full scale international port here today, the Haven has always played an essential role in the local community.

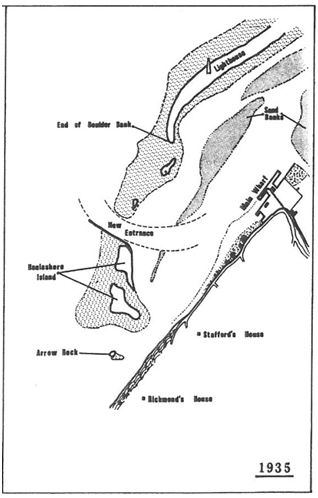

When Europeans arrived in Whakatu the region saw significant changes. The New Zealand Company and Arthur Wakefield founded the Nelson settlement on October 20th 1841. It was immediately apparent that the entrance to the Haven left something to be desired, but deep water inside the natural breakwater made up for what the entrance lacked. The settlement ships and first immigrant ships arrived in Nelson in 1842. The challenge of the Haven entrance was evident from the beginning, when the Fifeshire ran aground between Arrow Rock and Haulashore Island. By 1843 three jetties had been built, which served the settlement until the 1850's. At this time Nelson was the most popular destination for immigrant ships and had New Zealand’s second largest coastal fleet. In 1849 it was deemed that the Nelson “facilities were at capacity”1 and that expansion was needed in order to keep the settlement alive.

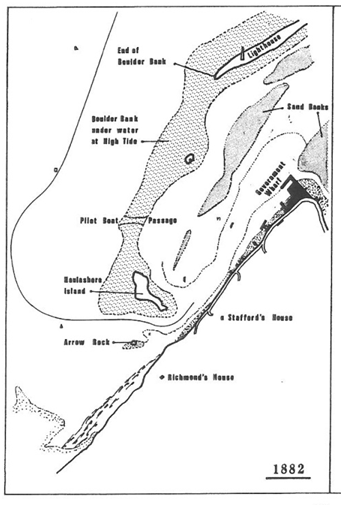

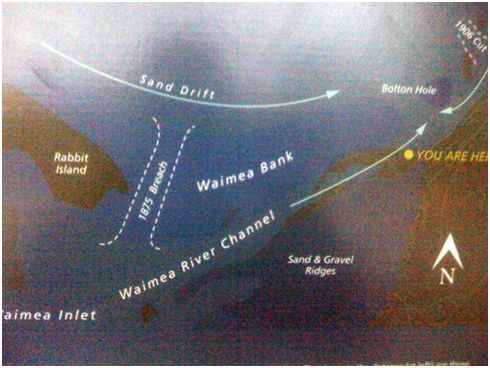

The Nelson Haven looked very different in the 1800's to what we know today. The Boulder Bank is a growing land feature and, in the past, the far reaching arm we know was below the high tide mark. Furthermore, the Waimea River flowed out on an eastern channel, right along the foot of the hills. The outflow of the harbour and the Waimea and Maitai rivers scoured the Old Entrance, preventing shoaling and maintaining the entrance depth of 17-22 ft at high tide. However, in 1875 after a storm, the Waimea River broke its banks and formed the western outlet. This channel change had significant repercussions for the harbour entrance. The new outflow pushed a sand bar further and further inshore, silting up the already dangerous opening. In 1878 it was realised that, with a depth of only 6 ft at low tide, something should be done.

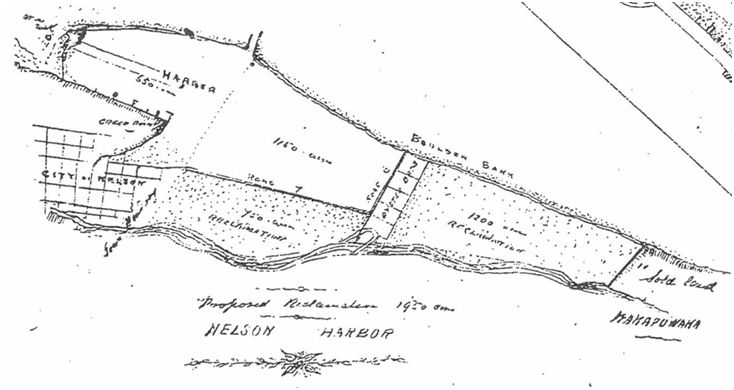

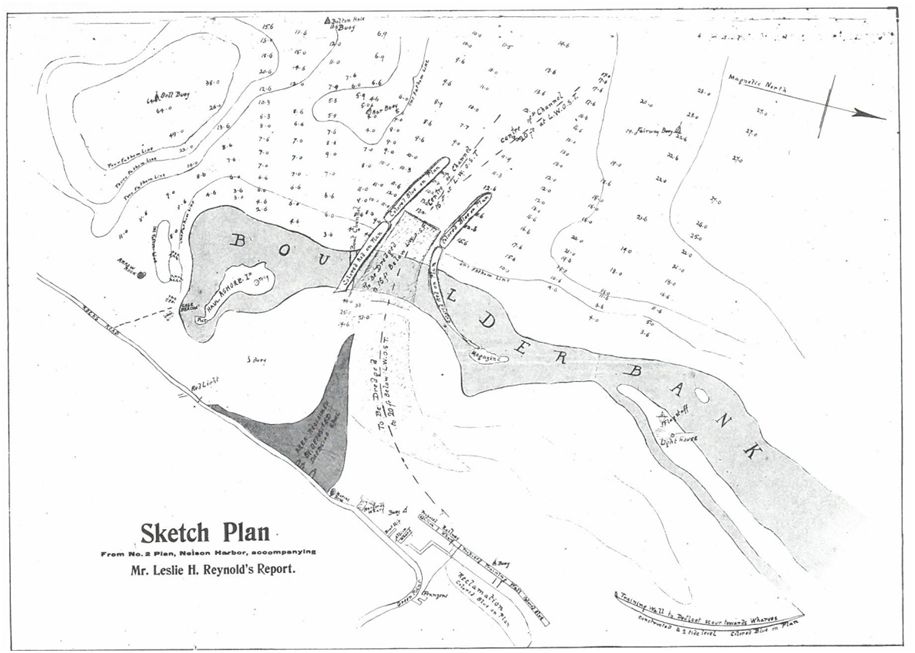

In 1886 an ambitious plan was proposed by William Akersten to make a cut in the Boulder Bank, extend the railroad out along a pier to reach deep water, and reclaim roughly half the Haven. This plan, however did not meet approval and it wasn’t until ten years later that the idea of making a cut in the Boulder Bank arose again. In 1899, engineer Mr Leslie Reynolds stated that development of the harbour entrance was essential to save Nelson from collapse, and he published a sketch plan. Reynolds’ plan dispensed with the railway and reclamation, recommending a more southern, 230m wide cut, with two seaward moles either side to protect the channel. Reynolds estimated the cost to be £58,000.

Reynold’s plan was better received than Akersten’s. Given the continued shoaling and increasing vessel size it was evident that action needed to be taken immediately, despite high costs, if Nelson was to remain a desirable port. A second engineer, Mr C. Napier Bell, was asked to give his opinion on the cut plan. Bell supported Reynolds’ proposal, however he suggested that the cut be made closer to the light house and estimated, more accurately, that the project would cost £85,000. Before the New Zealand Government would issue a loan to fund the Nelson Harbour Improvements, a Nelson Harbour Board had to be formed and the rate payers’ approval gained.

The Nelson Harbour Board Act was passed on the 20th of October 1900. The Nelson Harbour Board (NHB) was formed on January 20th 1901 and the Board elected John Graham as Chairman. First and foremost was the task to solve the entrance issue. It was at their second meeting, on April 6th 1901, after four ships ran aground coming through the Old Entrance, that Reynolds’ plan was adopted. In November the Government approved the plan and, in December, a vote of the Nelson community was conducted on whether a £65,000 loan should be taken out, at the rate payers’ expense, to make the Cut. The response was overwhelmingly positive, with 1274 votes for and only 66 against.2 This demonstrates the reliance of the community on the Port, even in Nelson’s early years.

Work began in 1903, removing and relocating small material from the Cut to form the northern part of Haulashore Island. Heavy material was saved for the construction of the moles. In late 1903 the NHB fell out with Reynolds and approached independent engineers T.H. Rawson and C.R.J. Williams for their judgment on the Cut plan. They advised a wider cut and suggested that only a heavier, southern mole be built. Following a vote, the NHB accepted their recommendations, terminating Reynolds’ contract on November 3rd 1903 and hiring Williams in July the following year. In 1906 John Graham and Mr Barrowman, the Resident Engineer, made the fateful decision to open the Cut early, so as to hasten its use. It was intended that dredging would continue but, following the breach of the dam, dredging became much more difficult. Dredging ceased entirely when a bottom width of 76m, at a depth of 4.4m at low water spring tides, was reached. This was half the designed width and a disappointment to many.

The official opening of the Cut took place on the 30th of July 1906 and was nonetheless a grand affair. The Rotoiti steam ship, packed with 800 passengers, did the honours of breaking the ribbon. The pilot declared that his time to return to port was a mere six minutes, down from the 17 minutes it took when negotiating the Old Entrance. John Graham was ecstatic, viewing it as one of his life’s greatest achievements. The making of the Cut saved Nelson from “not merely stagnation, but ruin,”3 despite the fact that it was prematurely opened.

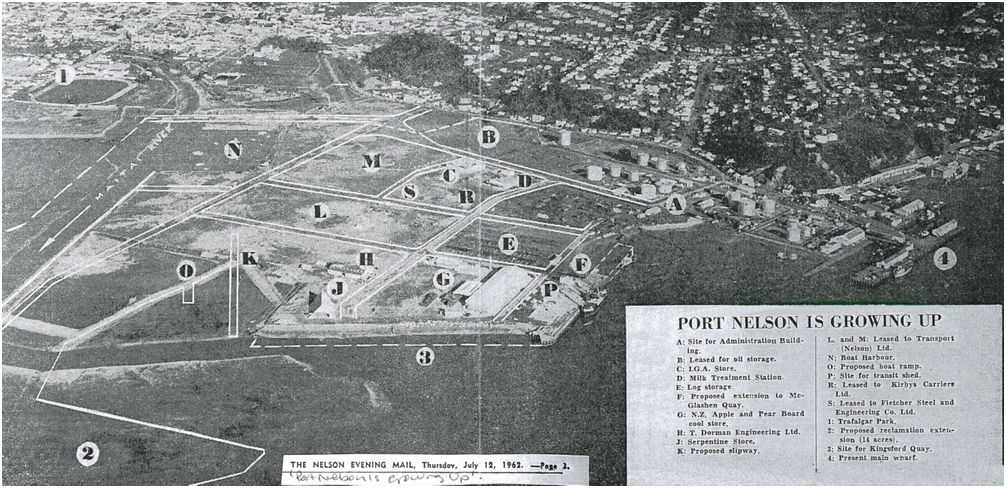

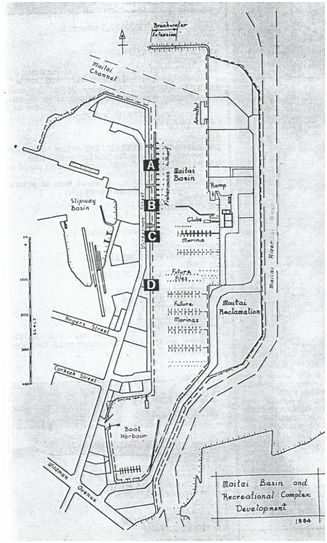

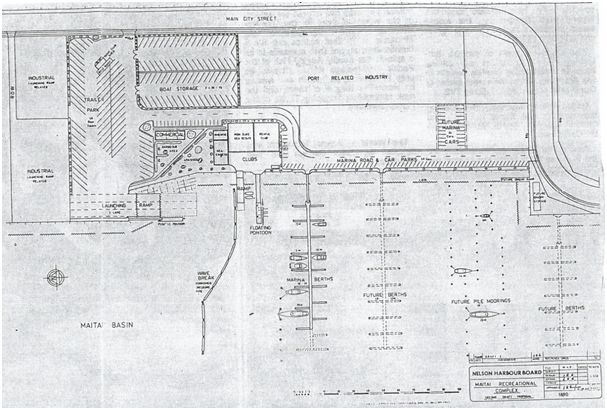

The 1960's reclamation satisfied the port’s commercial needs, however, in 1979 development for recreational purposes was recommended. The 14ha Maitai Reclamation design entailed, among other things, a new 38 berth marina, three-lane boat ramp, and combined club facility building for the Iron Duke Sea Scouts, the Talisman Sea Cadets, and the Rowing Club. On February 15th 1987 the centre was opened, with the hope that more locals would spend leisure time on the water.

All in all, around 80ha was won to transform Nelson from a struggling to bustling port. The sheer increase in throughput tonnage, 150,000 tonnes in 1945 to 1.2 million tonnes in 1984, illustrates the impact on Port Nelson. In 1988 it was reported that “the reclamation is one of Nelson’s most strategic industrial areas and a natural centre for the city’s marine services industries,”4 with benefits reaching the wider Nelson community.

Nelson was founded as a port and the Port remains an integral part of the City today. Even in 1960 it was evident to Mr S.A. Whitehead, MP, how important the port would become: “You must realise what a great asset the port will be to Nelson.”5 Port Nelson Ltd (PNL) replaced the Nelson Harbour Board in 1988. The company is a shared community asset, owned by the Nelson City Council and the Tasman District Council. Since its establishment, PNL has injected almost $122 million into the regional community, through dividends paid to the Councils as shareholders.6 Furthermore, roughly a third of the Nelson Tasman region’s Gross Domestic Product of $2.343 billion, in 2003, went through Port Nelson.7,8

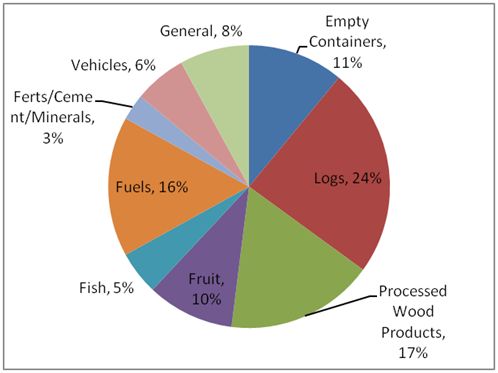

Port Nelson Ltd has an international focus that reflects this region’s production. In 1960, according to a Mr Parker, “No area in New Zealand produced such a wide range of primary and secondary products as Nelson.”9 Today, Nelson is renowned for forestry, fruit and seafood, having the “largest fishing port in Australasia”.10 In 2012 Nelson Pine Industries, Talley’s, Sealord, and Heartland Fruit lobbied for the inclusion of Nelson in Maersk’s new service to Asia, as the port provides a crucial means of efficient transport for their companies. Nearly 60% of Port Nelson’s throughput cargo is local exports. Due to the significant imbalance of exports over imports of goods, empty containers represent a significant percentage of the cargo volume through Nelson. PNL and the region’s local industries have a symbiotic relationship: together they thrive, without each other they would not survive.

Many people played major roles in the success of Port Nelson, notably Arthur Wakefield, Leslie Reynolds, John Graham, and D. Cadwell. Together they transformed not only the physical port of Nelson, but also the community. The Cut and the massive land reclamation have allowed Port Nelson to become the “region’s gateway to the world”11 for Nelson’s highly productive forestry, fruit and fishing trades. No doubt, as changes to trading methods and local production emerge, more significant development of the Nelson Harbour will arise. Nelson was founded as a port and will always be a port; its economic security and prosperity depends on it.

Monica Nelson, Nelson College for Girls, 2013

Additional information from Nelson Heritage Panel (Janet Bathgate)

In the beginning Port Nelson was just three jetties and land for port operations was restricted until the 1960's when Harbour Board General Manager W.H. Parr initiated a major reclamation scheme. This is now home to the port company's own operations and to a thriving service sector of marine support businesses. Port Nelson is a modern regional port with a reputation for the fast turnaround of ships that is demanded from a tidal port.

Regional produce

Within a decade of European settlement, apples were being shipped to Wellington and then to Australia. Every wooden carton of fruit was handled several times between the orchard packing house, the train to the wharf and the sling that finally lifted the boxes into the ship's hold. Pallets of cartons then streamlined the process, with most fruit leaving Nelson in large refrigerated vessels. Today almost all fruit is shipped in temperature controlled containers, much of it already packed in the trays that will go on show in supermarkets from London to Tokyo.

Fish from the sheltered waters of Tasman Bay used to be packed in baskets and carried on the passenger ferry to Wellington. In the 1970's larger fishing companies moved into offshore fisheries, the Port Nelson reclamation became the base for their processing factories and Nelson grew to become the biggest seafood port in Australasia. Today seafood exports include mussels and salmon from sustainable aquaculture in Tasman Bay and the Marlborough Sounds. Seafood too leaves Port Nelson for international markets in refrigerated containers.

Nelson's forestry industry dates back to settler times with early boat building and timber exports to Australia. In the 20th Century native timbers continued to be exported and even shipped off-shore as wood chips. With the growth in conservation awareness, this wood is now reserved for high-value uses. Exotic forests came on-stream from the mid 1900's. Pinus radiata logs are still an important export from Nelson, but investment in processing facilities adds value to exports such as Medium Density Fibreboard, Laminated Veneer Lumber and sawn timber. Product is shipped in packs or containers to markets in Australia, Asia and America.

2008. Updated June 2020

Story by: Monica Nelson

Sources

- Port History: Timeline. Retrieved from Port Nelson, 30 May 2013

http://www.portnelson.co.nz/about-the-port/port-history - Kingsford, A.R. (1947, October) ‘Harbour’s history struggle against elements. Nelson Evening Mail

- Coming Through the Cut 1906-2006 (2006, July) RePort Nelson, p.1

- Smith, T. (1988, September 24) Colourful and romantic era comes to end at Port Nelson Nelson Evening Mail

- Overseas ships require wider port entrance (1960, September 20) Nelson Evening Mail

- A positive year - against the odds (2012, December) RePort Nelson, p. 2

- Statistics New Zealand: New Zealand Official Yearbook 2010, p.473:

http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/digital-yearbook-collection/2010-yearbook - Statistics New Zealand: Regional GDP tables (June 2013)

- Luncheon Marks Official Opening Of Reclamation (1960, November 22) Nelson Evening Mail

- About the port: Fast Facts. Retrieved from Port Nelson, 16 May 2013:

http://www.portnelson.co.nz/about-the-port/fast-facts/ - About the Port

Further Sources

Books

- Allan, R.M. (1954) The history of Port Nelson Wellington, N.Z. : Whitcombe & Tombs

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/12565986 - Moore, B. (1990) Shaping up and shipping out: the last years of the Nelson Harbour Board. Nelson, N. Z. : Published by Port Nelson Ltd. under contract to the Board

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/84750140 - Nelson Harbour Board (1980) Port Nelson: the centre of New Zealand. Nelson, N.Z. : Nelson Harbour Board

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156307419 - Parr, W.H. (1979) Port Nelson - Gateway to the sea Nelson, NZ : Nelson Harbour Board

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154321043 - Warren, K. (2009) Rolling stones: Nelson's Boulder Bank : its place in our history and hearts. Nelson, N.Z. : Nikau Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/506383372

Newspapers

- Colonist, ‘Nelson Harbour Improvement’, Supplement, 10th Aug 1886

- Colonist, ‘Nelson Harbour Board’, Volume LVIII, Issue 14380, 4 April 1917, Page 3,

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Who was Nelson’s First Harbourmaster?’, 24th Feb 1959

- Nelson Evening Mail , ‘Nelson’s First Harbourmaster Was S. Carkeek’, 26th Feb 1959

- Photo News , ‘The Reclamation and McGlashen Quay...A Major Step Forward’, No. 2, Dec 1960

- Nelson Mail , ‘Port saves money on wharf revamp’, 5th May 1999

- Nelson Mail, ‘Reclamation takes five years’, 21st Sept 1999

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Intriguing link with port goes’, 10th Oct 1976

- Samuel, R., Nelson Evening Mail , ‘Ugly duckling was fairy godmother to Port Nelson’, 17-12-1988

- Clark, K., Nelson Mail, ‘Port’s new reclamation opens’, 12-9-2000

- Nelson Mail, ‘Reclamation takes five years’, 21-9-1999

- Nelson Mail, ‘Port saves money on wharf revamp’, 5-5-1999

- Bell, D., Nelson Mail, ‘Work transforms marina’, 23-9-1998

- Youngmeyer, D., Nelson Mail, ‘Planning ahead for major port project’, 20-6-1997

- Nelson Mail, ‘Wharf development’, 2-5-1997

- Collett, G., Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Upgrade of marina goes ahead at last’, 5-3-1988

- Hoddy, P., Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Nelson Harbour Board’, Supplement, 2-2-1987

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Harbour board backs doubling reclamation’, 6-8-1981

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Overseas ships require wider port entrance’, 20-9-1960

- Nelson Evening Mail, Karitea suction dredge pipeline to reclamation site (image), 1962

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Full steam ahead for port development’, 20-2-1985

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Tug muscle on parade’, 27-9-1983

- Nelson Mail, ‘New crane gives Port Nelson a lift’, 16-1-1998

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Luncheon Marks Official Opening Of Reclamation’, 22-11-1960

- Kingsford, A.R., Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Harbour’s history struggle against elements’, Oct 1947

- Mandeno, Lee, Brown, Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Nelson Harbour Scheme Proposal of Consulting Engineers’, 30-5-1939

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘A Picture From The Past’, 20-10-1962

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Harbour board chief predicts bright future’, 27-10-1990

- Youngmeyer, D. , Nelson Mail, ‘Direct link to North America good for port’, 21-2-1998

- Youngmeyer, D. , Nelson Mail, ‘Port Nelson plans $23.6m expenditure’, 26-9-1997

- Port Focus, ‘Blessing The Fleet’, July 2001

- Neal, T., Nelson Mail, ‘Big plans for ‘green port’’, 27-6-2009

- Nelson Mail, ‘Container line drops Port Nelson Coastal service planned’, 28-8-2010

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Port Nelson is growing up’, 12-7-1962, page 3

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘£12m. Reclamation Plan For Nelson’, 30-8-1966

- Nelson Evening Mail, ‘First step toward $24m. mudflat reclamation’, 13-9-1967

- Smith, T., Nelson Evening Mail, ‘Colourful and romantic era comes to end at Port Nelson’, 24-9-1988

Magazines

- The Port, Nelson: Tyree, photo, New Zealand Illustrated Magazine, 1 May 1904, Page 102,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/new-zealand-illustrated-magazine/1904/05/01/21 - Port Nelson Limited, ‘Coming Through the Cut 1906-2006’, RePort Nelson, July 2006, page 1, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘Making the Cut’, RePort Nelson, July 2006, Looking back, page 12, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘Opening up’, RePort Nelson, April 2007, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications, page 1

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘The Main Wharf’, RePort Nelson, March 2003, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, RePort Nelson, April 2009, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, RePort Nelson, Dec 2009, Image, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Bryce, M., Port Nelson Limited, ‘1906-2006 100 years as the regions gateway to the world’, RePort Nelson, July 2006, page 2, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘ The 2006-07 Year in Review’, RePort Nelson, Dec 2007, pages 6-8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘ The 2007-08 Year in Review’, RePort Nelson, Dec 2008, pages 6-8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘"The port was my life - I used to dream it", RePort Nelson, October 2001, Looking Back, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘The Main Wharf’, RePort Nelson, March 2003, Looking Back, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘The Cut’, RePort Nelson, August 1997, Looking Back, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘Lighting the Way’, RePort Nelson, December 1997, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, ‘Maurie Alborough and the Nelson Harbour Board’, RePort Nelson, December 2000, page 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

- Port Nelson Limited, RePort Nelson, December 2012, pages 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, Nelson Media Agency and SeeReed Visual Communications

Websites

- About the port: Fast Facts. Retrieved from Port Nelson, 16 May 2013:

http://www.portnelson.co.nz/about-the-port/fast-facts/ - Bell, J., ‘Making the Cut’. Retrieved from the Prow 16-5-2013

http://www.theprow.org.nz/making-the-cut/ - Marshall, S., ‘Construction of Rocks Road’: Retrieved from the Prow 16-5-2013

http://www.theprow.org.nz/construction-of-rocks-road/ - Porritt, A., ‘Nelson Harbour Board Order 1968’, New Zealand Legislation date accessed: 20-5-2013.

http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/1968/0135/latest/DLM28754.html - Port History: Timeline. Retrieved from Port Nelson, 30 May 2013

http://www.portnelson.co.nz/about-the-port/port-history - Port Nelson, ‘Port Nelson Annual Report 2012’, pages 4,5,6,14,

http://www.portnelson.co.nz/about-the-port/media/ - Sealord, date accessed: 28-6-13.

http://www.sealord.com/nz, - Statistics New Zealand: New Zealand Official Yearbook 2010, p.473:

http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/digital-yearbook-collection/2010-yearbook - Stephens, J., ‘Port Nelson timeline’. Retrieved from the Prow 16-5-2013

http://www.theprow.org.nz/port-nelson-timeline/

Maps

Images

- Nelson Provincial Museum, ‘Nelson Anchorages, [chart], 1850, [5.1.sn], A108

- Tasman Bay Heritage Trust, Nelson Provincial Museum, Pateena outward bound, FNJ 6X8

- Tasman Bay Heritage Trust, Nelson Provincial Museum, Rotoiti breaking the ribbon to open The Cut, 182161

Films

- Branford, R.G., and Parr, WH., The Film Archive, ‘Port Nelson 1949’, Medianet, Nelson Public Library

- The Film Archive, ‘Port Nelson ’80’, Nelson Public Library, http://10.1.1.235/browser/view.html?id=F196560

Port Nelson Resources

- 2013 Map of Port Nelson 1:6000

- Tide and Datum Levels (at 1014mB)

- PORT NELSON LTD – Wharf Statistics

Information Boards

- Nelson City Council, (n.d.), Beach development, by beach tennis courts, corner Bisley Walk and Hounsell Circle, photographed on 8-6-2013