Marlborough women at war

New Zealand nurses served in both World Wars, providing devoted care to the war sick and wounded and displaying great courage. In 1914, Sister Ethel Lewis accompanied 400 patients from the frontline of the Serbian Campaign.

New Zealand nurses served in both World Wars, providing devoted care to the war sick and wounded and displaying great courage. In 1914, Sister Ethel Lewis accompanied 400 patients from the frontline of the Serbian Campaign. “The nurses… pushed forward on foot, through the mountain passes of Albania, often with snow up to the knees, with rations reduced to one slice of bread per day, and no shelter at night except what they could find. They frequently slept in pigsties. Patients died daily and not one survived the retreat. One died on Sister Lewis’s back after she had carried him two miles.”1

Here are the stories of some Marlborough nurses who served on hospital ships and in theatres of war.

Hospital Ships

Edith Rudd (nee Lewis) served in World War 1 (WW1) and World War 2 (WW2) and was matron of Wairau Hospital for 20 years between the wars.2 She enlisted with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS), sailing from Wellington on the Marama in December 1915, and served in Egypt until 1918.3

She describes the difficult conditions in her book Joy in the Caring: “The convoys would bring us some heavy cases from the Western Desert and looking back now we think how much could have been done…… had we had some of the modern drugs and advanced knowledge of surgery we have today…it was a continual battle to get good results, especially when the condition of the patient was depleted from malnutrition and sometimes malaria.”4

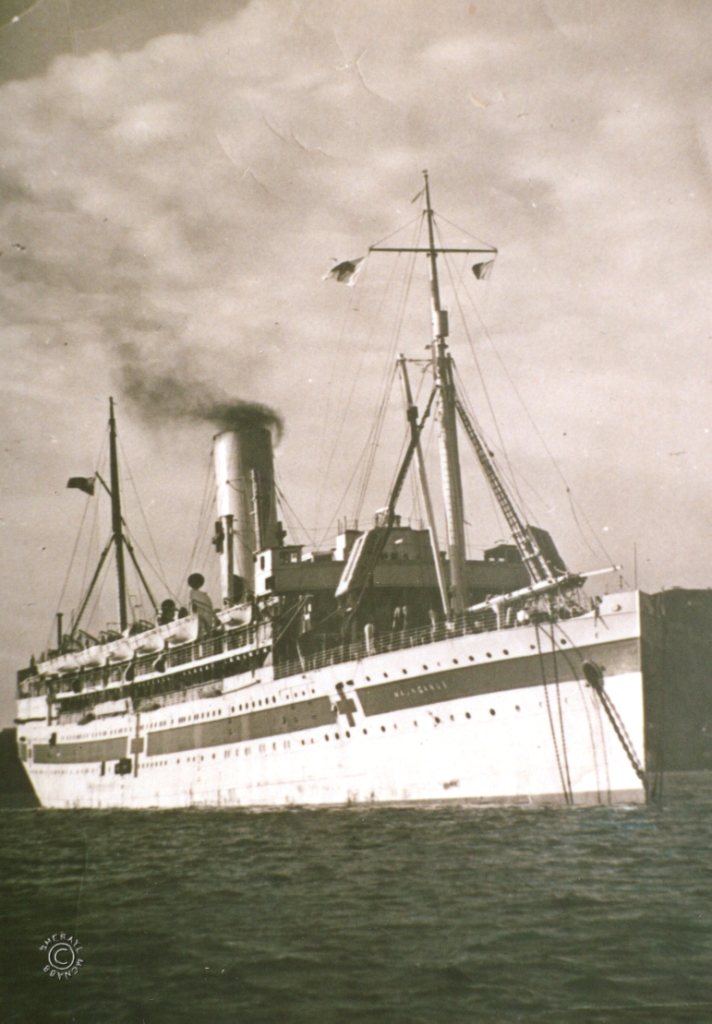

On 22 April 1941, the NZHS Maunganui left Wellington for Suez with Matron Lewis on board and in charge of 20 nurses. The ship was converted to carry 390 patients and, by 1945, had transported more than 5,600 patients - mostly home to New Zealand.5 Matron Lewis became known as 'Momma of the Black Dressing Gown'. At night during blackout conditions, wearing her black silk dressing gown, she checked on her patients in the wards and on the decks.6

Matron Lewis was awarded campaign medals for both of the World Wars. She also received the highest military nursing award, the Royal Red Cross First (1st Class) in 1944 and, in 1961, she was presented with the highest distinction in nursing, the Florence Nightingale Medal.7

Sister Iris Young joined the NZANS in August 1941 and joined Matron Lewis on the Maunganui in December. In July 1942 she was posted to No. 1 New Zealand General Hospital (1NZGH) in Egypt and later went to Italy with 1NZGH and served with No. 1 NZ Mobile Casualty Clearing Station before returning to New Zealand in 1945. Mrs Allan (nee Young) lives in Blenheim and turned 100 in May 2014.8

Serbian Campaign

Mary O’Connor was born in 1890 at Fairhall and trained as a nurse at Wairau Hospital. She joined the NZANS as a staff nurse in 1915 and travelled to Egypt. Sister O’Connor served in Serbia and Albania.9

When Bulgaria entered WW1 on Germany’s side in 1915, the Serbian military forces were quickly overwhelmed. This forced a desperate retreat through mountainous terrain to the Albanian coast and Corfu.10

By January 1916, Sister O’Connor was in charge of the Officers' Enteric Ward at No. 2 General Hospital in Egypt.11 She served on the British Hospital Ship Dunluce Castle, from March to November 1916.12

Sister O'Connor was later recalled from Egypt to the No.3 New Zealand General Hospital in Wiltshire, where she was brought to the notice of the British Secretary of State for War for valuable services rendered during the war. She was awarded the Royal Red Cross (2nd Class) and the Serbian Samaritan Cross.13

Meanwhile Back at Home

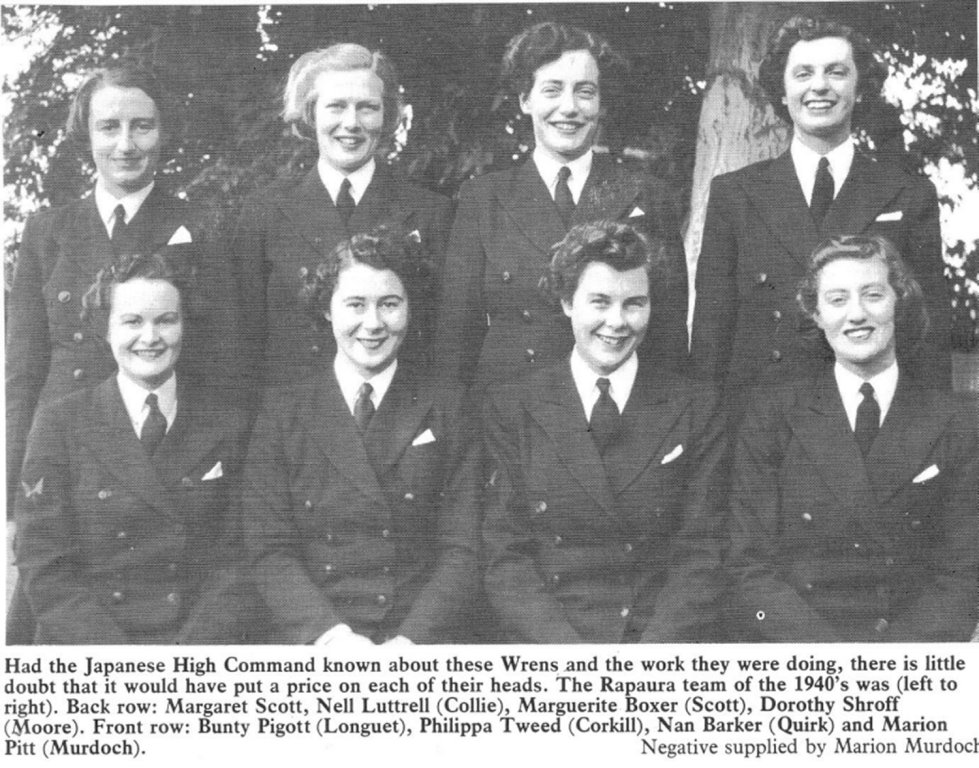

In 1942, Mr Bob Dosser’s farm at the end of a long dusty road in Rapaura was found to suit the Navy’s need for secrecy. After very careful screening, eight Wrens (The Women's Royal Naval Service) were chosen to staff a wireless station at the farm, where ‘very highly specialised and secret work was performed.”14

Rapaura was a radio fingerprinting station set up with sophisticated oscilloscopes and cameras to record signals for detailed analysis that could distinguish signals from each enemy base, ship or submarine. It was vital work at a time during the war when there were real fears that Japanese forces might invade New Zealand.15

The especially trained Wrens listened to and recorded Japanese radio transmissions and helped establish a pattern of finger prints. This gave the Navy an accurate picture of enemy naval activity in the Pacific.16

In Doing our Bit: New Zealand Women tell their Stories of World War Two, edited by Jim Sullivan, one of the operators, Bunty Longuet (nee Pigott) said:

“We would sit down and listen on headphones. You’d graze around the frequencies until you heard some Morse code and you’d write down what you heard… The Japanese always began their transmissions with the same letters so we knew it was them.

“We were told it was not a question of ‘if’ the Japanese came but ‘when’. When it happened we were to destroy our code book and then destroy ourselves. But they never actually went into what we would do with ourselves.”17

Bunty and her fellow operators, who were all trained in the Japanese Katakana code, worked in four-hour watches between 6pm and 6am.18 All of the personnel involved in the Rapaura Naval W/T station were held under an oath of silence from the Ministry of Defence until 1982.19

2014. Updated Dec 2020

Story by: Joy Stephens

Sources

- A Gallant Nurse (1916, October) Kai Tiaki : the journal of the nurses of New Zealand, 9(4) p.23

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19161001.2.34 - Lewis, E.M. (1963) Joy in the Caring, Christchurch, N.Z. : N.M. Peryer,p.4

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/14623151 - Information supplied by: Marlborough RSA, 2014

- Lewis, p.55

- New Zealand Military Nursing: http://www.nzans.org.

- Lewis, back cover.

- Marlborough RSA

- McNabb, Sherayl (http://www.nzans.org) by email 07/04/2014

- Brewer, M. (2009) New Zealand’s association with Serbian awards to female medical personnel of the Great War. Retrieved from New Zealand Military Nursing:

http://www.nzans.org/Honours/Serbian%20Awards.html - World War I: Great Serbian Retreat (1916). Retrieved from Historical boys clothing:

http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww1/cou/ser/w1cs-ret16.html - News of our Nurses in Egypt (1916, January) Kai Tiaki : the journal of the nurses of New Zealand, 9(1) p.43

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19160101.2.45 - New Zealand Army Nursing Service (1916, July) Kai Tiaki : the journal of the nurses of New Zealand, 9(3), p.149

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19160401.2.15 - Brewer, M.

- RNZN Communications Association. Chapter 9 WRNZNS. Retrieved from:

http://rnzncomms.org/ourhistory/chapter9/ - Small frame contained a full and colourful life (2010, November 22). Dominion Post. Retrieved from Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/obituaries/4367538/Small-frame-contained-a-full-and-colourful-life - RNZN Communications Association

- Sullivan, J. (Ed.) (2002) Doing our bit: New Zealand Women tell their Stories of World War Two, Auckland, N.Z.:HarperCollins. p 139-145

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50560612 - Small frame contained a full and colourful life

- RNZN Communications Association. Chapter 9 WRNZNS. Retrieved from:

http://rnzncomms.org/ourhistory/chapter9/

Further Sources

Books

- Bardsley, D.(2000) The Land Girls: In a Man's world, 1939-1946, Dunedin, N.Z.: University of Otago Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/46539847 - Ellis, E. (2010) Teachers for South Africa: New Zealand Women at the South African War Concentration Camps, Paekakariki, N.Z.: Hanorah Books.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/682557131 - Kendall, S. & Corbett, D. (1990) New Zealand Military Nursing: A History of the R.N.Z.N.C. Boer War to Present Day, Auckland, N.Z.: Sherayl Kendall & David Corbett.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28218270 - Montgomerie, D. (2001) The Women's War: New Zealand Women 1939-45, Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland University Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/47816862 - Mcgarry, I. (2010) New Zealand's Vietnam War: a History of Combat, Commitment and Controversy, Auckland,N.Z.:Exilse Publishing.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/641982333 - Parr, A. (2010) Home: Civilian New Zealanders Remember the Second World War, New York: Penguin.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/705902315 - Rees, P. (2008) The Other ANZACs: Nurses at War 1914-18, Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/649827454 - Rogers, A. (2003) While You're Away: New Zealand Nurses at War 1899-1948, Auckland, N.Z.: Auckland University Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53392960 - Sullivan, J. (Ed.) (2002) Doing our bit: New Zealand Women tell their Stories of World War Two, Auckland, N.Z.:HarperCollins

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50560612

Newspapers

- Carnahan, C. (2014) Nelson nurses and WWI. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 7(6), pp.34-45

- Herselan, G. (2014, April 23) Wartime nurses awarded for service. Marlborough Express.

http://www.stuff.co.nz/marlborough-express/news/9969263/Wartime-nurse-awarded-for-service - [Betty Longuet] Small frame contained a full and colourful life (2010, November 22). Dominion Post. Retrieved from Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/obituaries/4367538/Small-frame-contained-a-full-and-colourful-life - Tolerton, J. (2013, November 11). Dominion Post. Retrieved from Stuff:

Women's role in war overlooked (http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/comment/columnists/9385045/Womens-role-in-war-overlooked

From Papers Past:

- Letters from Our Nurses Abroad (1916, July) Kai Tiaki : the journal of the nurses of New Zealand, 9(3), p.139

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19160701.2.26 - [Mary O'Connor] Personal (1919, March 4) Marlborough Express, p.4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19190304.2.17 - Nurses for the front (1915, May 24) New Zealand Herald, p.5

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NZH19150524.2.53 - Nurses in Serbia (1916, April 15) Dominion

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=DOM19160415.2.60

Websites

- Barlow, F. (nd) NZ Navy Wrens in secret ops during WW2. Retrieved from Maritime Radio:

http://maritimeradio.org/awarua-radio-zlb/1940-1949/working-with-wrens/ - Brewer, M. (2009) New Zealand’s association with Serbian awards to female medical personnel of the Great War. Retrieved from New Zealand Military Nursing:

http://www.nzans.org/Honours/Serbian%20Awards.html - Bunty Longuet (2010, December 5) Sounds Historical. Radio New Zealand. Podcast:

http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/soundshistorical/20101205 - Dixon, G. [Director](1992) In fear of invasion [documentary]. Film Archive, Wellington: 2006.1424

https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/collections/catalogue/catalogue-item?record_id=105400 - Great war hospital ships, Retrieved from the Regimental Rogue, 10 April 2014:

http://regimentalrogue.com/misc/great_war_hospital_ships.htm - Mary O’Connor. Cenotaph database record.

https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/C52071 - Military history of New Zealand in World War 1. Retrieved from Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_New_Zealand_in_World_War_I - New Zealand Military Nursing.Retrieved 10 April 2014

http://www.nzans.org - New Zealand nurses World War One, 1914-1922. Retrieved from Rootsweb:

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~sooty/nurses.html - Nurses in Serbia.(1916, April 15) Dominion,p.11.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=DOM19160415.2.60 - Pemberton-Pigott Lenore Liocardia (also known as Betty Longuet). Cenotaph database record:

https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/C132970 - Samaritan Cross (1920, May 11) The Edinburgh Gazette, p.1241

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/Edinburgh/issue/13594/page/1241 - Ward, F. (2014) Scott, Jessie Ann, from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3s7/scott-jessie-ann