Maungatapu Murders - The notorious Burgess Gang

The trial of the notorious Burgess gang caused a sensation in the small town of Nelson in 1866. Murder was a rare crime and this one involved not just one, but five victims, and everyone was desperate to know all the grisly details.

The trial of the notorious Burgess gang caused a sensation in the small town of Nelson in 1866. Murder was a rare crime and this one involved not just one, but five victims, and everyone was desperate to know all the grisly details....

Murder on the Maungatapu

The story began with the mysterious disappearance of five men on the Maungatapu track between Nelson and the Wairau in mid June1866. The first victim was travelling alone from Pelorus, and then it was the turn of a group of four from Deep Creek, on the Wakamarina goldfield.

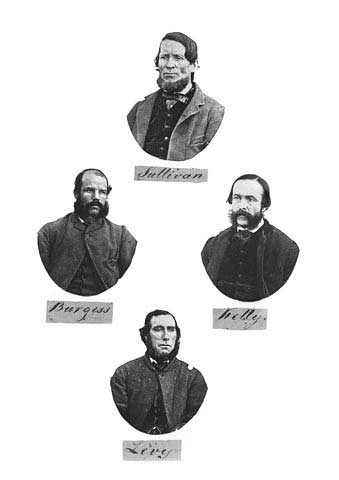

The perpetrators were Richard Burgess, Philip Levy, Thomas Kelly and Joseph Sullivan, hardened criminals who had served prison time in England, Australia and Otago for robbery and burglary. Collectively known as the Burgess gang, they had arrived in Nelson via the Otago and West Coast goldfields on June 6, 1866 and decided to rob a bank in Picton.

A change of plan saw the gang returning from Canvastown to the eastern side of the Maungatapu track. The new strategy was to lie in wait for men heading for Nelson from the Wakamarina goldfield and rob them of money and gold.1

On June 12 they strangled and suffocated James Battle, a 54-year old whaler who had been working as a farm labourer at Pelorus. The robbery netted them a mere three pounds and seventeen shillings.2

The following day, the gang hid behind a large rock and ambushed a group of four men travelling from the Wakamarina to Nelson with a packhorse. Led off the track into dense bush, storekeepers John Kempthorne and James Dudley, innkeeper Felix Mathieu and miner James de Pontius were variously strangled, stabbed and shot. Having removed a quantity of gold and money, the gang loaded their victims’ swags onto Old Farmer, the horse, led him into the bush and shot him.3

The men were missed almost immediately by their friends, and a large search party, including men from the Maori community, was soon on the hunt for them.4

Meanwhile the gang had slunk back to Nelson, where they spent money cleaning themselves up and buying new clothes.5

Local newspapers were full of the story of the “goldfield rogues” and the “supposed case of sticking up”.6

The failure of the search to find the missing men fed fears that they had been murdered. Suspicion fell on the free spending gang members and they were all in custody by the evening of June 19.7

Sullivan took advantage of a Government offer of a 200 pound reward or a free pardon for any accomplice and turned Queen's evidence. He told police he was only the lookout, while the other three were responsible for the murders of all five missing men.8

Information from Sullivan led to the location of the bodies of the Mathieu party on June 28, following the finding of Old Farmer by Hemi Matenga from Wakapuaka.9 The bodies were carried to Nelson and were viewed by thousands of people in the engine shed, which acted as a temporary morgue. This building still stands in Albion Square. Two days after the funeral the body of James Battle was found, and he was buried in the same grave. Nelsonians paid for a five-sided monument to stand over the shared grave at Wakapuaka Cemetery.10

Burgess wrote his confessions while in gaol.11 All four men were convicted of the murders, with Burgess, Kelly and Levy being hanged at the Nelson Gaol on October 5, 1866. Their bodies were buried in unconsecrated ground behind the gaol. Sullivan's death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he served time in Dunedin before being pardoned in 1874 and returning to England.

In a grisly twist, the dead men's heads were removed from their bodies and plaster casts made from them. This was done in a bid to support the theories of phrenology, a pseudo-science that sought to determine personal characteristics by examining the shape of an individual's head.12 The casts are held in The Nelson Provincial Museum (not on display).

Additional note

The bodies of the hanged men were not afforded the dignity of a proper burial. On the night following the executions the bodies were buried in the gaol yard. Over time some of the remains have almost certainly been dug up and possibly mistakenly reburied as Maori remains. 13

About the Maungatapu Track. 14

The unsealed 40-kilometre Maungatapu track is currently closed to vehicles but can be walked or tackled on mountain bikes. It runs from the Maitai River Forks up to the Maungatapu Saddle and down into the Pelorus Valley. The infamous Murderer’s Rock is 4.3km from the summit on the Pelorus side.

2008

Updated: Apr 3, 2020

Story by: Karen Stade

Sources

-

Johnston, M. (1992). Gold in a tin dish : The search for gold in Marlborough and eastern Nelson : Volume one : The history of the Wakamarina goldfield. Nelson, N.Z.: Nikau Press. pp.167-8, 183.

-

Johnston, 184, 186.

-

Johnston, 188-191.

-

Johnston, 197-204

-

Johnston, 192-195.

-

Supposed case of sticking up. Missing men. (1866, June 19), Nelson Examiner. p.5.

-

Johnston, 204-208.

-

Johnston,. 214-217.

-

Mitchell, H. & J. (2007). Te Tau Ihu O Te Waka: A history of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough: Volume 2, Te Ara Hou: the new society. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia Publishers, p.323.

-

Johnston, 218-221, 237.

-

Burton, David (1983). Confessions of Richard Burgess: The Maungatapu murders and other grisly tales. Wellington, New Zealand: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

-

Johnston, 230-237.

-

Johnston, 237-238.

- Maungatapu/Moketapu. One of a series of short films made for Nelson City Council for te wiki o te reo 2019:

http://www.nelson.govt.nz/services/community/tohu-whenua-sites-of-significance/maungatapumoketapu-mt-maungatapu/

Further Sources

Books

- A full history of the Maungatapu murders : Including a narrative of the events preceding the murders, confessions of Sullivan &Burgess, a corrected report of the trial, detailed particulars of the execution of Burgess, Kelly and Levy, and lives of the murderers, with portraits, and plans and sections of the road. (1866). Nelson, N.Z.: Printed and published at the Examiner Office. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155723722

- Abraham, C. J. (1866). Ahab's crimes and the Maungatapu murders, treated on the principles of the new school of morals and religion. Auckland N.Z.: Printed at the Cathedral Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155721526 - Armstrong, D. A., Haig, T., Warren, J., & Nelson District Law Society. (2005). Beyond the Maungatapu : The history of the Nelson District Law Society and the legal profession of the Nelson district, 1842-2000. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson District Law Society.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156517848 - Berry, K. (1986). The Pelorus. In Scrutiny on the county. (pp. 43-55). Blenheim, New Zealand: The Marlborough County Council.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154634052 - Burgess, R., & Burton, D. (1983). Confessions of Richard Burgess : The Maungatapu murders and other grisly crimes. Wellington N.Z.: Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/11782583 - Clune, F. (1959). Murders on Maungatapu : a history of the crimes committed on the lonely slopes of Maungatapu (the sacred mountain) in New Zealand in the year 1866. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6642832 - A full history of the Maungatapu murders : including a narrative of the events preceding the murders, confessions of Sullivan & Burgess, a corrected report of the trial, detailed particulars of the execution of Burgess, Kelly and Levy, and lives of the murderers, with portraits, and plans and sections of the road (1866) Nelson, N.Z. : Printed and published at the Examiner Office.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155723722

(note - this complements the Luckie publication, which comprises articles from the Examiners' rival paper, the Nelson Evening Mail) - Gee, Maurice (1978). Nelson Central School: a history. Nelson, New Zealand: Nelson Central School Centennial Committee.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/152750768 - Halket Millar, J. (1954). Death round the bend. Nelson, N.Z: R.W.Stiles.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35019558 - Hawes, P., & Webb, P. (2003). Outlaws & rogues. Auckland N.Z.: Whitcoulls.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/156219616 - Hodgson & Friend. (1866). A series of sketches illustrating the principal incidents in connection with the Maungatapu murders : With portraits of the prisoners from photographs taken in Nelson goal. Nelson N.Z.: Old Post Office.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155724405 - Johnston, M.R (1992) Gold in a tin dish, Volume one: the history of the Wakamarina goldfield . Nelson, N.Z. : Nikau Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32973337 - Kempthorne, Renatus (2001). The Kempthornes of New Zealand their history. Nelson : Author.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155992691 - Luckie, D. M. (1890;1909;). The Maungatapu Mountain murders : Being a narrative of the murder of five men between the Wakamarina River and Nelson by Burgess, Levy, Kelly and Sullivan in 1866 : With an account of their capture, trial, conviction and execution : Also some particulars as to their lives and career in New Zealand. Nelson, N.Z.: H.D. Jackson [Nelson Evening Mail]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/153647572 - Luckie, D. M. (1866). Illustrated narrative of the dreadful murders on the Maungatapu Mountain and track between the Wakamarina River and Nelson, in the province of Nelson, New Zealand. Nelson, N.Z.: Nation & Luckie.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155724895 - Luckie, D. M. (1924). The Maungatapu Mountain murders : A narrative of the murder of five men between the Wakamarina River and Nelson,by Burgess, Levy, Kelly and Sullivan, in 1866, with an account of their capture, trial, conviction and execution ; also, some particulars as their lives and career in New Zealand. Nelson, N.Z: R.W. Stiles and Co.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/153647572 - Mabille, T. (1866). The Maungatapu murders : Illustrated by twenty different views and portraits, from sketches taken on the spot with a correct map of the road from Deep creek to Nelson. Nelson, N.Z.: T. Mabille.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154147220 - Martin, W. (2016) Murder on the Maungatapu : a narrative history of the Burgess Gang and their greatest crime. Christchurch, New Zealand : Canterbury University Press

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/951444487 - The Maungatapu Murders : Being newspaper articles on the Burgess-Sullivan gang, including the series published in the Press, Christchurch, (6 August – 20 August 1938).

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155989675 - McIntosh, A. D. (1940). New Marlborough. In Marlborough, A provincial history (pp. 301-302). Blenheim, New Zealand: Marlborough Provincial Historical Committee.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4654822 - Neale, J. (1986). The Nelson Police: the story of the Nelson police district 1841-1986, Nelson [N.Z.] : New Zealand Police, Nelson District.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/37360879 - Price, Felicity (2002) No Angel. Christchurch, New Zealand: Hazard Press. [Fiction story about the mistress of Richard Burgess.]

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/64575220 - Wastney, P.V, (1982).Roads of yesterday Whangamoa, Wakapuaka and Maungatapu [Nelson, N.Z.] : P.V. and N.L. Wastney.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35100270

Newspapers

- Barnett, S. (2004, Oct) Murder in the hills. New Zealand wilderness, 26-29

- 'Glittering prospects' toilsome journey over the Maungatapu (1989) Journal of the Nelson and Marlborough Historical Societies. 2(3)25-26.

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ05_03-t1-body1-d5.html - Jimson, K. (2016) Selling murder. Journal of the Nelson and Marlborough Historical Societies. 8(2) 7-13.

- Maungatapu Murders (1971) New Zealand's heritage, v. 3. Sydney: Hamlyn Paul, pp.908-914.

- On the Maungatapu track.(2005) NZ today,14, 66-69.

-

Skinner, H.D.(1913) Article XLIX: An Ancient Maori Stone Quarry. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand for the Years 1868-1961, 46, p.324-5.

http://rsnz.natlib.govt.nz/volume/rsnz_46/rsnz_46_00_005820.html - Treadwell, C.A.L (1933, June 1). Famous New Zealand Trials: The Maungatapu Mountain Murders. The New Zealand Railways Magazine. 8(2) 9-12.

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-Gov08_02Rail-t1-body-d3.html

Read how The Nelson Examiner and the Nelson Evening Mail reported the murders in 1866.

These newspapers are available on microfilm at Elma Turner Library, Nelson, on microfilm at the Nelson Provincial Museum’s research facility and on microfilm at Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. The newspapers are available digitally on the website Papers Past website at http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

The Nelson Examiner

- Supposed Case of Sticking Up. Missing Men (1866, June 19) The Nelson Examiner. p.5.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660619.2.29 - The suspected murders on the Maungatapu (1866, June 23) The Nelson Examiner. pp.2-3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660623.2.7 - Supposed Murder of Men on the Maungatapu.(1866, June 26) The Nelson Examiner. p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660626.2.7 - Reward for recovery of bodies and advertisement for search fund (1866, June 28) The Nelson Examiner. p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660628.2.8.2 - Confession of one of the murderers, recovery of four bodies (1866, June 30) The Nelson Examiner.p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660630.2.5 - The Maungatapu murders. (1866, July 4) The Nelson Examiner.p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660704.2.6.1 - Inquest (1866, July 3) The Nelson Examiner. p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18660703.2.8 - Court examination (1866, July 3) The Nelson Examiner. p.3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660703.2.9l - Burgess confesses, committal of four men for murder of Battle(1866, August 11) The Nelson Examiner. pp.3-4. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660811.1.3

- The trial (1866, September 13) The Nelson Examiner. p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660913.2.9 - Phrenological notes on the four murderers. (1866, September 25) The Nelson Examiner.p.3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18660925.2.11 - The execution. (1866, October 6) The Nelson Examiner. p.2.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18661006.2.8 - Phrenology examination of Levy and Kelly (1866, October 11) The Nelson Examiner. p.3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18661011.2.11 - Monument designs (1866, October 16) The Nelson Examiner. p.2-3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18661016.2.6

The Nelson Evening Mail

-

The supposed murder at the Maungatapu. (1866, June 19). Nelson Evening Mail. p.2.https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660619.2.8

- Civil cases. (1866, June 20). Nelson Evening Mail. p. 3. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660620.2.11

- Maungatapu murders. (1866, June 23). Nelson Evening Mail. p.2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660623.2.6

- Resident Magistrate’s Court, this day. (1866, June 26). Nelson Evening Mail. p.2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660626.2.6

- Confession of Sullivan. (1866, June 29). Nelson Evening Mail. p.2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18660629.2.6

- The Nelson Mail. (1866, October 24). Nelson Evening Mail. p. 2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18661024.2.8

Websites

- McLintock, A.H. (Ed)(1966; 2009) Sullivan, Joseph Thomas, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/sullivan-joseph-thomas/1

-

McLintock, A.H. (Ed)(1966; 2009) Burgess, Richard, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/burgess-richard/1 -

McLintock, A.H. (Ed)(1966; 2009) Levy, Philip, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/levy-philip/1 -

McLintock, A.H. (Ed)(1966; 2009) Kelly, Thomas, from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/kelly-thomas/1 - Maungatapu murders (2007). Retrieved 29th October, 2008 from Wikipedia:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maungatapu_murders

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2016, December 21). Murder on the Maungatapu track.

- Notable Trials (2007, 18 September) In McLintock, A.H. (ed.) (1966) An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. From Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand:

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/trials-notable/4

Maps

Unpublished - available at Nelson Provincial Museum

- Burgess, Richard, (1829-1866). Autobiography; letter 1886. Ref: qMS BUR

- Curtis family. Correspondence 1852-1866. Letters of 1866, including those of Mrs Frank Nairn, comment on Maungatapu murders. Ref: qMS CUR

- Hodgson & Friend.(1886) A series of sketches illustrating the principal incidents in connection with the Maungatapu murders, with portraits of the prisoners from photographs taken in Nelson Gaol. [Originally published as a pamphlet 1866]. Ref: UMS 1284

- Maungatapu murders papers.[A file of material relating to the Maungatapu murders} including the Ref: UMS 209

- Maungatapu murders newspaper articles, periodical articles, Subject file

- Nelson Provincial Government. (1866, June 27) 400 pound reward...murdered on the Maungatapu mountain. Ref: Poster folder 7

- The pioneers : a series of ten lectures on the early days of the settlement of Nelson. Ref: MS MOO

- Various incidents of the Maungatapu tragedy ; illustrated from sketches and photographs taken on the spot by Hodgson and Friend, Nelson.(c.1866) Nelson, N.Z.: Hodgson and Friend. C1866. Ref: Poster folder 7

Other places to visit

- Maungatapu Track Ride the mountain bike track and see Murderer's Rock where the Burgess Gang lay in wait for five of their victims. https://www.heartofbiking.org.nz/other-trails/cycle-touring-routes/mangatapu-track/

- Wakapuaka Cemetery Visit the cemetery where the five murder victims are buried beneath a memorial paid for by the people of Nelson. The obelisk memorial is in the Anglican section, on the right side of the hillside behind the chapel. http://www.nelsoncitycouncil.co.nz/cemeteries-in-nelson-2/

- The Nelson Provincial Museum See the plaster head casts of Burgess, Kelly and Levy, items from the Nelson goal, the poster advertising the 400 pound reward and a pardon for an associate, a revolver believed to be associated with the murders and a series of paintings by Janice Gill illustrating the murders and the execution. http://www.nelsonmuseum.co.nz/

- Hallowell Cemetery Map

This historic cemetery on Shelbourne Street used to sit behind the old Nelson gaol where three of the four Maungatapu murderers were hanged. They were buried within the gaol grounds in a location now on private property behind the block of apartments on Shelbourne Street. A walkway up to the tree-filled cemetery is to the left of the apartments. In 1908 the Girls' Central School opened on the site of the old gaol and pupils recall being told the murderers' bodies were buried under a concrete slab to on the eastern side of the main school building (Gee, p.56). The school buildings were later used by the Nelson Education Board before being demolished for the apartments.

The four murderers, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Museum Collection, LS9.3.7

The four murderers, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Museum Collection, LS9.3.7 The death masks of Kelly, Burgess and Levy, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Museum Collection, M539

The death masks of Kelly, Burgess and Levy, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Museum Collection, M539 Maungatapu Murder Memorial (Karen Stade)

Maungatapu Murder Memorial (Karen Stade)