Te Tau Ihu and World War II

The war years in Te Tau Ihu followed a decade of economic Depression. Regional development halted, austerity, shortages and later rationing were the order of the day.

The war years in Te Tau Ihu followed a decade of economic Depression. Regional development halted, austerity, shortages and later rationing were the order of the day.

The progress of war

The war had little impact in the first nine months. Recruiting was low key but large crowds in Nelson farewelled the troops which departed just before Christmas 1939. In the country towns, for example Murchison and Motueka, the "Empire spirit" still ran high and farewell socials extolled the cause of the Empire.

Enlistment was slow in Nelson and conscription was introduced nationally after thee British suffered heavy losses in the middle of 1940. New Zealand, and Nelson, did not feel an immediate threat from the war however, until the end of 1941 when Japanese forces threatened the whole Pacific region. The surrender of Singapore in February 1942 was a "stunning blow" - a thrashing by a "yellow race" and local defence was actioned.1

The Emergency Precautions Scheme (forerunner of Civil Defence) dug trenches and installed barbed wire at Nelson airport and foreshore2 and organised blackouts along the coast. Night-time fishermen and Tahunanui residents were slow to take this seriously and turn off their lights.3 Disused mine shafts at Puponga were cleared in case they were needed as shelters.4

The establishment of RNZAF Station Nelson (1941-1946) at Nelson Airport was a significant development in Nelson’s mid-20th century aviation history. RNZAF no.2 squadron was based in Nelson from January 1941 to April 1943. With an operational squadron defending the city and region, thousands of young men and women passed through the station. Many Nelsonians were killed on air force service overseas (and some in New Zealand) during the war years.

One of those who successfully survived the war was Nelson born RAF pilot Leonard Trent, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for combat in Europe in 1943. Another survivor and VC recipient was Sgt Clive Hulme of Nelson, awarded for bravery in Crete in 1942. He received his award on the Church Steps.

The local economy, shortages and rationing

Many items were in short supply during the war. One of the first things to have an impact was a shortage of black stockings. By October 1940 the headmistress of Nelson College for Girls, following British wartime precedents, led the way into liberalism and economy by permitting the girls to have bare legs and tennis socks.5

Other shortages were perhaps more serious. Lack of petrol affected deliveries of all supplies, and prevented people travelling for both business and pleasure. The A&P shows were suspended in 1942 and 1943, as well as the celebrations for the Nelson City Centennial in 1942. Essential food was subject to rationing and farmers were meant to send their produce for centralised processing and marketing rather than supplying home and local needs. Nelson was one of the dairying regions notorious for flouting butter laws in the early years of the war, with farmers continuing to churn their own butter and sell to local shops outside the coupon system, rather than sending their cream to creameries for national distribution.6

Nelson fruitgowers could not ship produce to England, as only meat and wool was prioritised for transport. The government stepped in and guaranteed a price, so free apples were distributed to school children. Nelson fruit juice was promoted nationally for its health-giving properties. The government established dehydrating factories in Motueka in 1943, and three other locations in New Zealand, following a request from the USA to supply their troops with dehydrated products.7

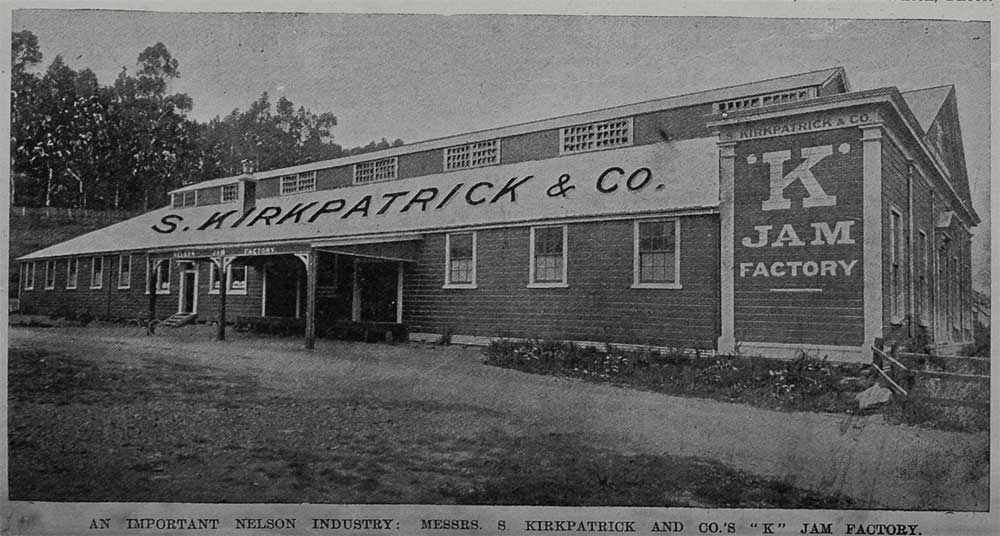

Berry farmers thrived, as jam was on the list of supplies wanted for troops overseas. Vegetables suitable for canning were also in high demand and Kirkpatrick's Factory prospered.

Labour, volunteering and women

Labour shortages hit after 1941. Many women entered voluntary, paid and peace-time war work. Locally Dorothy Atmore, wife of Nelson MP Harry Atmore, organised the Women's National Reserve and Nelson women formed an auxiliary corps keen to train for any emergency work.8 Volunteers also prepared packages for troops overseas, picked fruit and took on paid work in the canning factory. To assist with the harvest, by 1943, older primary school children were allowed time off to work in the fields.

All labour ("manpower") was directed nationally. Some work allocated to women proved very unpopular, for example 13 young Nelson women lodged appeals against working in the Ngawhatu mental hospital.9

Aliens

The loyalty of Nelson's German community, which had suffered abuse and discrimination during World War I was well established by World War II and there was little backlash against them. For the Italians it was a different matter, with some harassment, occasional searches of fishing boats, opening of mail and occasional abuse and stoning of glasshouses.10 Some young Italian Nelsonians joined up for the allies, for example Mario Monopoli, who was killed in action in 1945.

Pacifism

Nelson was one of the areas which hosted strong pacifist communities - largely Christian and Methodist. The Christian Pacifist Society founded 1936, had active members in the Riverside Community at Motueka, established by Hibert and Marion Holdaway and Harry Yuill. It became a refuge for pacifists and sometimes absconders. One of the early members was A.C. Barrington, a relatively high profile figure amongst the many men at Riverside, who refused to fight in World War II and were imprisoned in the North Island. Riverside children were harassed at school and the community was generally derided as ‘bloody pacifists' during and after the war.

Fundraising

The Government urged the community to raise funds to support the war effort. Local fundraising contributed $5000 for the spitfire fund and a local National savings Committee made regular contributions to the war fund.11 Loan campaigns and fund-raising community events were regular features of the war years. Tākaka farmers took a cut from each cream cheque for the war fund.

Nelson Māori joined a national effort of Māori to support the significant efforts of the 28th Māori Battalion.12

The end of the war

Nelson, as everywhere, breathed a sigh of relief at the end of the war welcoming peace and hopeful that the City would now be able to develop and prosper. A "spectacular and colourful" Peace Day celebration was held on the Church Steps in August 1945.13 Similar processions were held in Richmond and throughout the District, followed by special services for the returned service men later in the year.14

Remembering the war and those killed in action

The first Labour Government, and the responsible Minister, Bill Parry, did not want to fund more ornamental memorials. Instead the names of World War II servicemen killed in action were added to existing structures erected for World War I. In the place of new memorials, the government provided a subsidy, pound for pound, for useful ‘living memorials’. The memorial was to be a ‘community centre where the people can gather for social, educational, cultural and recreational purposes'.15 Stoke and Wakapuaka Memorial Halls are examples of such community centres.

There are two examples of memorials erected specifically for World War II in Nelson. The Anzac Park Waharoa was erected in 2011, to remember dead of the Māori Battalion, formed in World War II. Another is the HMS Neptune Memorial on Wakefield Quay. This is a memorial to four Nelson men, killed in the New Zealand Navy's worst incident involving loss of life. HMS Neptune ran into a minefield on December 19, 1941 off the cost of Libya, with a total of 764 crew members killed with only one survivor; 150 were New Zealanders. A grim reminder of the realities of war.

2022

Story by: Nicola Harwood

Sources

- Singapore has fallen (1942, February 16) Nelson Evening Mail, p.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19420216.2.35 - Kerr, A. (1998) Memories Of Nelson Aerodrome In World War II. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 6(2), pp.26-28

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ06_02-t1-body1-d5.html - Blackout trial (1942, February 23) Nelson Evening Mail, p.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19420223.2.50 - Puponga prepares (1942, February 31) Nelson Evening Mail, p.6

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19420213.2.87 - Taylor, N.M. (1986) New Zealand People at War: the home front. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch. vol.2, p.843

- Taylor, vol.2, p.823

- May expand, Motueka dehydration plant at Motueka (1945, April 21) Nelson Evening Mail), p.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19450421.2.31 - Taylor, vol.2, p.1069

- Taylor, vol.2, p.679

- Taylor, vol.2, p.769

- National Savings (1945, June 28) Nelson Evening Mail, p.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19450628.2.46 - Maori Battalion Christmas (1942, December 9) Nelson Evening Mail, p.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19421209.2.49 - Peace Day Service (1945, August 16) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19450816.2.9.2 - Smoke Concert. A victory celebration (1945, November 16) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19451116.2.9 - Official circular on war memorials, 22 October 1946, Archives New Zealand (IA 1,174/1/2)

Further Sources

Books

- Bell, C.W.(1979) Unfinished business: the second fifty years of the Nelson City Council. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson City Council, pp.15-30

http://www.worldcat.org/title/unfinished-business-the-second-fifty-years-of-the-nelson-city-council/oclc/34523816 - McAloon, J.(1997). Nelson: A regional history. Whatamango Bay, N.Z, Cape Catley Ltd, pp.180-185

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50310188 - Taylor, N.M. (1986) New Zealand People at War: the home front. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-2Hom-c16.html

Newspapers

- Kerr, A. (1998) Memories Of Nelson Aerodrome In World War II. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 6(2), pp.26-28

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ06_02-t1-body1-d5.html - Sivignon, C. (2022, April 23) Son seeks details of father's 'top secret' World War II exploits. Nelson Mail on Stuff:

https://www.stuff.co.nz/pou-tiaki/128405645/son-seeks-details-of-fathers-top-secret-world-war-ii-exploits

Websites

- Jock Phillips, 'Memorials and monuments - Memorials to the centennial and the Second World War', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 11 May 2022)

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/memorials-and-monuments/page-6