Lyell

The highs and lows of goldmining Graveyards have an international reputation for being 'spooky', but when you are standing in the graveyard of a deceased town, 'spooky' takes on a very different connotation.

The highs and lows of goldmining

Graveyards have an international reputation for being 'spooky', but when you are standing in the graveyard of a deceased town, 'spooky' takes on a very different connotation. Lyell attained a population of over two thousand and was the chief producer of gold in the Buller district. It created opportunities for aspiring miners and accommodated to the needs of their families. However, all that can be viewed from this once bustling community are decaying headstones, landslide-ridden dray roads and remnants of buildings.

The discovery of gold

Julius Von Haast explored the South West area of the Nelson region during the mid 1800's, and in his travels named the "continuous rocky chain ... with magnificent needles and points"1 the Lyell Range. Sir Charles Lyell was a British geologist who was the "father of modern geology.'2 Sir Lyell is attributed with the theory behind mountains forming after plate movement over hundreds of years, and scientists, such as Charles Darwin, built much of their work on Lyell's three volumes of 'Principles of Geology'. It is commonly accepted that Sir Lyell did not know of the settlement's existence, nor of its rich surroundings, and although Haast also never visited the town, his admiration for Sir Charles Lyell, and the consequent naming of the area, perfectly highlights the rugged and mountainous environment that contained the town.

Māori prospectors were the first to obtain gold from the Lyell region, and potentially sparked a prosperous gold rush for the area. Native Māori knew of the gold's existence in the Lyell area, but due to their fascination with greenstone, they did not prize it. However, after Eparara, a Māori prospector, and four other miners, discovered a 'dumbbell' shaped nugget weighing 19½ ounces, 'up the creek named Lyell, by Haast',3 pakeha began to recognise Lyell as a potential gold mining area. Eparara and his team fossicked for gold in a tunnel through solid rock, one mile upstream from the bridge today. This discovery resulted in the desertion of other gold mines, and the establishment of the town know as Lyell.

As reports of significant gold discoveries in Lyell infiltrated the mining community, miners from all over the world made their way to the isolated settlement. By 1863, 100 miners from other gold fields had set up camp along the creek and benefited greatly from the nuggets found which weighed between 17 and 52 ounces. In one report, five Irishmen claimed to have uncovered 500 ounces (1.4 kilograms)4 in five days. Twelve men organised themselves into a 'Vigilance Committee', to regulate the claim sizes and prevent Australian gold miners dispossessing Māori prospector's findings; on two occasions they threatened the Australians with lynching. However, they did not need to enforce it on either occasion. As well as Australians, miners came to Lyell from Greece, Italy, Switzerland, England, Scotland, Ireland, India and America. Prosperous mining reports kept international excavators interested in the Lyell area and consequently the population began to rise.

Transport

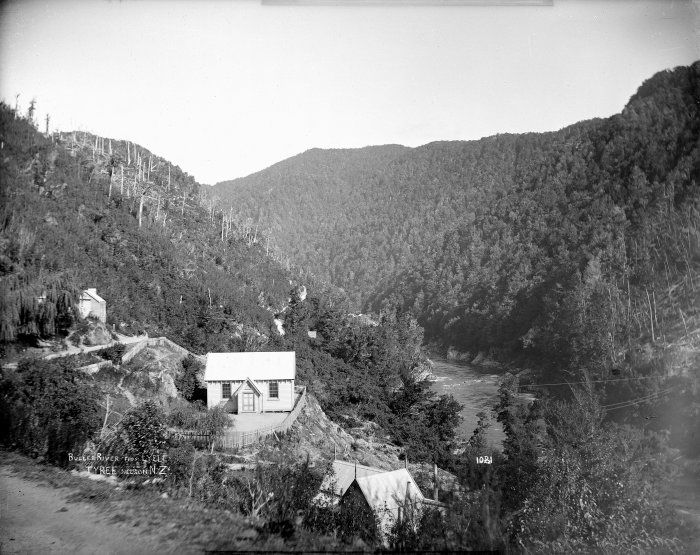

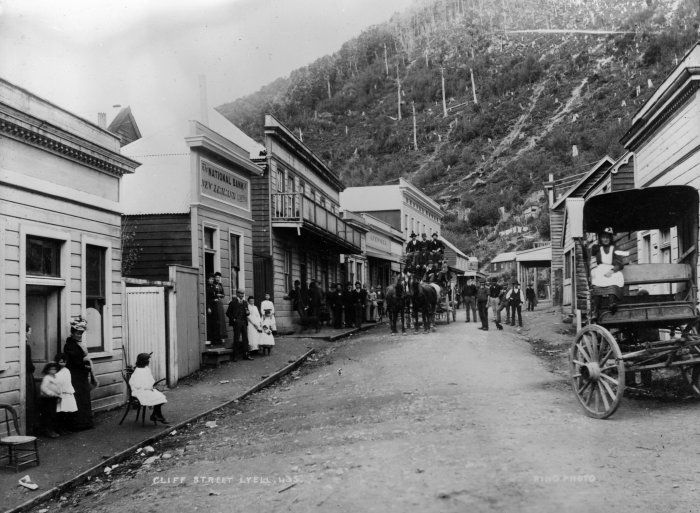

Transport to and from Lyell was treacherous as the Buller River was the sole contact with exporters and other settlements. Lyell was described as 'the most inaccessible goldfield in New Zealand'5, with Māori the only canoeists strong enough to paddle against the powerful rapids. William Stuart, one of the first residents of Lyell, depicted his journey up the Buller river in his journal and explains 'canoes are poled and paddled, towed by ropes... then pulled by all hands'6 until they finally reached their destination. Early horse roads were created as well as tracks but they were often rough and unstable for carts, so in 1870 a road was laid down called Cliff Street - which became the main, and only, street of Lyell - and was extended in 1877. Soon after, a road was made along the Buller River, which made travelling to Lyell significantly easier. Consequently, as the transportation system developed, women and families were able to venture into Lyell as they centralised the mining community.

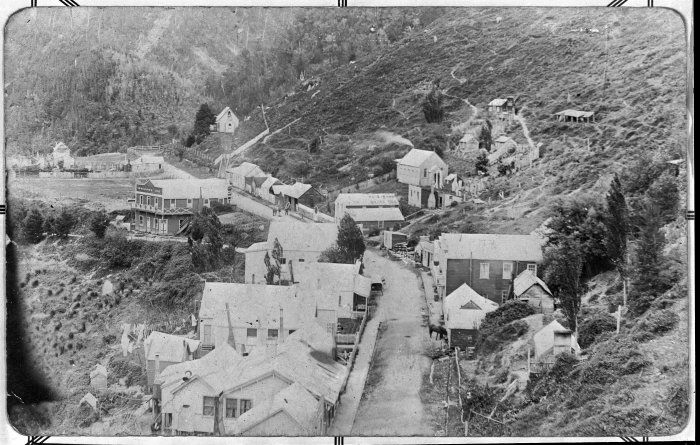

Access to Lyell became somewhat easier for the wives and families of the miners during the late 1860's and early 1870's and they began to move to Lyell. In the early 1870's, the arrival of women encouraged the miners to move from their tents which lined the creek, into a more civilised home. As the population of the town grew, more shops were quickly erected. Previously miners had only come to town at the weekends. Numerous general stores, as well as a butcher, a cordwainer, a news agency and a hotel, lined Cliff Street, behind which were several houses and tents. As more females arrived in Lyell, prospectors from the Lyell Creek moved in to the town, and soon a community was created.

Expansion of the town

As the town expanded further and became more settled, a newspaper was established in 1880 known as the 'Lyell Argus', only to be changed later to the 'Lyell Times'. The 'Lyell Argus' consisted of four pages, with international, local and mining news as well as advertisements and general notices. Sold every Saturday for sixpence, the equivalent of five cents today, the 'Lyell Argus' held important information for Lyell's residents, from touring circuses to the opening of The National Bank. The establishment of the towns' newspaper allowed the residents of Lyell and other members of the community who lived up the Lyell Creek, to keep informed about the town, country's and world's news.

As children were born in Lyell, or were brought there by canoe, the demand for adequate education rose. The journey down river to Westport was a dangerous and tiresome one, so Lyell residents erected a school to educate their children, in the year of 1874. Photographs show the school was situated on the Nelson side of the town, on a small flat piece of land. The roll rose from 52, when the school opened, to 86, in Lyell's heyday, the period of greatest success. Complications with the hiring of the school's teacher proved a difficulty, and in 1892 the school opened late due to the absence of one. Although problems arose for the Lyell school, its existence ensured that the education of the miners' families would not be affected by their isolation.

Lyell citizens were predominantly of the Roman Catholic and Anglican faiths, which both required their own separate churches in which the residents could attend. Erected in 1874, the Saint Matthew's Church of England allowed the Anglican residents of Lyell to continue to exercise their faith. It was a regularly used church which held a donated organ, from Mrs Sadlier, and was the church of A.E Ashton, the only clergyman to live in Lyell. Reverend Father Cummings was the Reverend for the Saint Josephs Church. He travelled from Reefton to Lyell once a month to hold mass. The Saint Josephs Church was built in 1876 due to the large population of Irish and Italian miners who lived at Lyell and wanted to show their faith for the Roman Catholic beliefs. Both Saint Matthews and Saint Josephs Church were an important part of the Lyell community as they allowed its residents to practice their faith in a dignified and honourable way.

Health care

Health care was poor in Lyell, with scurvy and other diseases common due to the extensive journey from Murchison. Illness often resulted in death as there was no doctor that lived in Lyell, and by the time he arrived up the Buller River, it was often too late. However, in January 1886 the Lyell Times published an advertisement for 'George Levien, Surgeon Dentist, Chemist and Druggist... to attend patients at the Commercial Hotel'.7.Unfortunately he did not stay long, but his visit was greatly appreciated among the Lyell people. After his trip, residents attempted to fundraise for a Lyell hospital, but the amount raised, £109 and nineteen shillings, was not enough to begin this endeavour. Consequently, the townspeople of Lyell often died young due to the lack of medical care in the area.

Lyell's heyday

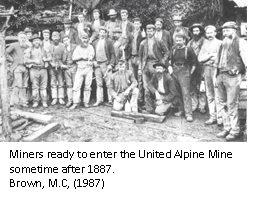

As the town thrived, quartz was mined by companies from the reefs behind Lyell, supplying the many miners with more stable jobs. The quartz had to be bashed by a battery, a piston powered by water which fell on the quartz, to obtain the gold inside - this form of mining was the main income for Lyell during its existence. Machinery was brought from Melbourne via Westport and was then allocated to the various mines in the area. The largest mine in Lyell was called the United Alpine, which opened four miles up the Lyell Creek in 1874. Its establishment brought much success to Lyell with its twenty head battery, which 'crushed fifteen tons of quartz per eight hour shift,"8 and also the employment of up to two hundred men at one time. Although the town itself was growing, wealth was brought into the area by the surrounding mines which obtained quartz from the hills behind Lyell.

From 1880 to 1896, Lyell experienced its heyday. Lyell had grown at an efficient rate due to the presence of gold quartz in the neighbouring reefs which created a stable and successful atmosphere within the town. Cliff Street was lined with banks, hotels, a post office, courthouse, police station, brewery and newspaper agency, which all of Lyell's residents benefited from greatly. A small farm across the Buller River supplied much of the town with milk and vegetables which were transported across the river in 'a box... that was propelled across the river by pulling on ropes.'9 This device enabled the residents to cross the Buller River, although there were often complications resulting in death. During this time, regular contact with neighbouring communities began, with a regular coach travelling from Lyell to Nelson. However, this prosperous period was short lived.

Biddy of the Buller10

Bridget Goodwin, or "Biddy of the Buller" as she was known, was possibly Lyell's most famous resident. A formidable woman, even though she was only four feet in height. She left poverty in Ireland for the lure of the Australian goldfields in the mid 1800's. There she befriended two men, and left with them for New Zealand in the 1880's, where they worked the Collingwood goldfields. Fossicking their way down the Buller, they arrived in Lyell in the 1890's - Lyell's heyday. There she lived with the two miners in a one room hut where the iron bridge crosses the Buller. The community may have been scandalised by her living arrangements, and her drinking, but she did not care - and worked alongside her two men, eventually outliving both, working up until she was 80. At that age she decided her body was worn out and she settled into a two room cottage in Reefton, where she died in 1899 aged 86.

Decline

Several large, disastrous fires encouraged Lyell's decline after its successful, gold mining heyday. Water was well supplied in Lyell, with a reservoir on the spur above the town and a water tank above the Post Office Hotel; however there was not enough to extinguish the fire of 1896, so it was left to freely demolish the National Bank, three hotels, several stores as well as residents' houses. Although there was no loss of life, some townspeople, such as Mr John Fennell, lost up to £8,000 when six buildings he owned were burnt to the ground. People began to rebuild and six months later Lyell was 'beginning to look like it used to.'11

However, prospectors and their families began to leave Lyell after the New Alpine Mine closed in 1906. The mine was the largest employer in the area and supplied the miners of Lyell with a regular income. Its failure meant the families in Lyell would no longer have sufficient income or employment, so many residents moved to the West Coast or to other mining towns, such as Wakamarina, to find employment. The closure of Lyell's biggest Quartz mine led to the desertion of their once thriving town. Another fire in 1926 saw the destruction of the Lyell post office, court house, library and school and this resulted in the further abandonment of Lyell.

On the 17 June, 1929, the Murchison area was struck by a magnitude 7.8 earthquake, which left Lyell completely cut off from the rest of New Zealand. No buildings in Lyell were severely damaged; however, the roads leading into the town had numerous landslips along them. The slips isolated Lyell as no one was able to leave or come into the town; this resulted in numerous people dying as doctors were not able to get to Lyell in time. The Buller road was closed for 18 months and until it was cleared the townspeople had to walk out to get their supplies. The earthquake encouraged more people to leave, as it reinforced how isolated they were from the rest of the country.

By 1951 the only remaining building in Lyell was the Post Office Hotel; however it too was destroyed by a fire in 1963. The Post Office Hotel had been built in 1874 by a man called Mangos. It had seen the establishment, heyday and decline of Lyell, and held the majority of Lyell's historic artefacts. Mr Cox, the owner of the hotel, hopelessly watched as his hotel, home and history, was engulfed in a 'mass of flames'12 and burned to the ground in less than half an hour. By 1963, few remnants of Lyell remained after the last Hotel was burned to the ground.

A historical reserve

Lyell is now a historical reserve with walking and biking tracks surrounding a grass camping ground. The Department of Conservation and the Department of Lands and Surveys, established Lyell as a historical reserve to remember Lyell's existence. Today, visitors are encouraged to pan for gold, in the ‘gold fossicking reserve' on the Lyell Creek, and are able to camp at the site of the old town. Historic boards and plaques have been erected by both departments to show visitors what life was like for the residents of Lyell and how much the area has changed. These boards also show the few remaining pieces of evidence of the town.

Dray roads and walking tracks from the camping site lead to significant areas in the town's history. One such site is the United Alpine mine and Croesus mine, whose battery is still there. Other paths lead to the neighbouring towns of Zalatown and Gibbstown, old building sites, and the tunnel in which gold was first discovered by Māori in 1862. Yet the most popular walk is only five minutes from the camping ground and leads to the old cemetery of Lyell. Surrounded by dense bush, this cemetery has a handful of headstones enclosed by iron railings. Although much of Lyell's history and buildings have been destroyed, the cemetery has been preserved in an attempt to remember the lives of those who lived here.

Lyell today is a very different place to what is was 100 years ago. It is hard to imagine, when standing in the historic reserve, that people used to live here. Amongst the blackberry and gorse there were houses, shops and hotels. Surrounded by forested hills, it is a beautiful place to be. Yet when you are standing in the graveyard of an abandoned town, it does seem 'spooky'.

The Old Ghost Road

Lyell is now the starting (or finishing point) for the Old Ghost Road, which has increased interest in, and visits to, the site since it was completed in 2015. The old gold miners’ road has been revived as a mountain biking and tramping trail – connecting the old dray road in the Lyell (Upper Buller Gorge) to the Mōkihinui River in the north. The 85km-long Old Ghost Road traverses native forest, open tussock tops, river flats and forgotten valleys, after following the dray road to Lyell Saddle Hut.

Steph Russell, Nelson College for Girls, 2011.

Updated December 2021.

Story by: Steph Russell

Sources

- Brown, M.C, (1987), Lyell, the Golden Past, p. 3

- Ibid, p. 4

- Ibid, p. 11

- http://www.metric-conversions.org/weight/ounces-to-grams.htm, date accessed 23/06/2011

- Brown, M.C, (1987), p. VII

- Ibid, p. 13

- Brown, M.C, (1987), p. 47

- Hoskyn, D, (October 1977), Proposed Historical Reserve at Lyell, p.1

- Brown, M.C, (1987), p. 53

- Hindmarsh, G. (2020, February 8) Pint-sized goldminer's larger than life adventures in Buller. Nelson Mail on Stuff

https://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/news/119290790/pintsized-goldminers-larger-than-life-adventures-in-buller - Ibid, p. 78

- Unknown, The Nelson Evening Mail, 11/03/1963

Further Sources

Books

- Boatwright, M. (2016). Spirit to the stone: building the Old Ghost Road. Wellington, N.Z.: Bennett Y. Slater.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/951958895 - Brentnall, J. (2012). The Laundress of Lyell. Ebook available on Scribd.com.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/100885976/The-Laundress-of-Lyell - Brown, M. C. (1987). Lyell: the golden past. Murchison, N.Z. : Murchison District Historical & Museum Society.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35287574 - Hindmarsh, G. (2017). Kahurangi stories: More tales from Northwest Nelson. Nelson, N.Z.: Potton & Burton, p. 66-79.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1010939172 - Latham, D. (1992). The golden reefs: an account of the great days of quartz-mining at Reefton, Waiuta & the Lyell. Nelson, N.Z.: Nikau Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/33443036 - May, P. R. (1962, reprinted 1967). The West Coast Gold Rushes. Christchurch, N.Z.: Pegasus.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8091938 - Ristori, B. (1961, reprinted 1981). The Land I Love: an intimate journey through Nelson Province with B. Ristori. Nelson, N.Z.: Anchor.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154271348

Newspapers

- Brown, M.C (1977) Extracts from Some Early Newspapers of the Upper Buller Area. Nelson Historical Journal, 3(3), p.32

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ03_03-t1-body1-d11.html - Hoskyn, D., ‘Proposed Historical Reserve at Lyell', Nelson Newsletter Committee, New Zealand

- Smith, D. (2015) Matakitaki gold. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 8(1), pp.11-25

- The Alpine Mine.(1907, January 19). Nelson Evening Mail, p.4.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19070119.2.44 - The Lyell: its past history. (1879, June 26). Colonist, p.4.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC18790626.2.14 - Lyell Mining. (1887, February 14). Inangahua Times, p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/IT18870214.2.8 - Township of Lyell.(1926, February 16 ).The Nelson Evening Mail. p.4.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM19260216.2.41 - United Alpine Lyell. (1891, May 4). Inangahua Times, p. 2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/IT18910504.2.9

Websites

- Lyell, In: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Nelson, Marlborough & Westland Provincial Districts] (1906). Retrieved from NZETC

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d3-d3.html - Orr, K.W. 'Goodwin, Bridget', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 21 September 2020)

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1g14/goodwin-bridget - Rob, ‘Gold Nuggets of New Zealand', Gold Dredging Forum. Retrieved 17/05/2011

http://golddredgingforum.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=articalsofinterest&action=display&thread=72