Pakihi - Māori and Business

Maori in Te Tau Ihu were already experienced traders when settlers arrived in 1842

The new Nelson settlement offered consistent opportunities for enterprise on a scale not previously seen, and Māori were prepared. In December 1841 Arthur Wakefield suggested that if his brother William (in Wellington) knew anyone with bullocks and plough he should send them to Nelson with seed potatoes – “It would teach the Maoris a lesson, who are holding back for more population. They have got 50 tons of potatoes in reserve”.1

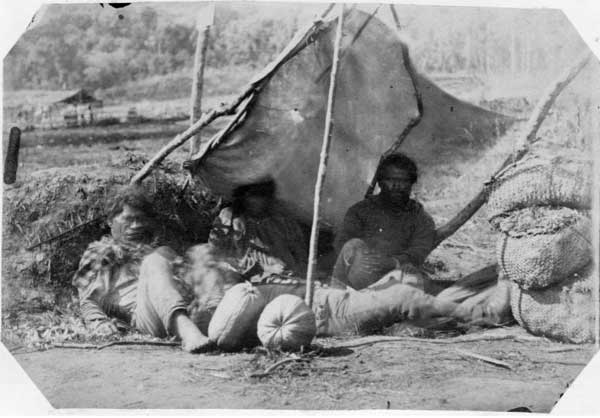

For the first few years of European settlement Māori quickly grasped openings to provide goods and services in order to obtain new products, and construct or commission European-style houses, churches and boats. They grew large quantities of potatoes, vegetables and melons, sold fish, shellfish and pork, expanded into wheat and barley, provided firewood, and exchanged weavings and carvings for money or clothing and/or good blankets.

They also provided guiding services, ferry services across rivers and bays, and assisted new settlers to travel to their land blocks and construct their first houses. Some crewed on European-owned ships, but most Māori were reluctant employees, preferring to maintain their traditional lifestyle and independence.

Initial trades were often for barter or exchange, but Māori quickly learned the value of money, as one settler commented: “… they were remarkably shrewd at driving a bargain, had a very appreciative opinion of their commodities, and a critical knowledge of the value of the ‘utu’ (money) and the goods taken in exchange”. 2

In 1847 Māori in the Nelson region had 340 acres of wheat, 300 of potatoes, 80 of maize, and 50 of other crops. The following year, with the inclusion of Marlborough, the returns jumped to 1,137 acres in wheat, 211 in maize, 290 in potatoes and 120 in other crops. Almost all work of ground preparation, planting, tending and harvesting was done communally, by hand; a few employed Europeans to plough for them. Wheat was taken to mills in Riwaka or Nelson, as one early Riwaka settler recalls:

The Maoris from Aorere, Collingwood, used to bring their wheat up to be milled. The canoes were able to come right up to the mill as it was alongside a tidal creek. These canoes were some 60 and others 70 feet long and carried 14 to 15 paddles on each side. 3

Some flour was for Māori use, the rest for sale.

Māori used the proceeds from their hard work to buy blankets, European clothing and footwear, tobacco, flour and sugar, horses and coastal ships. In 1853, five of the seventeen ships registered at Port Nelson were Māori-owned.

Māori flourished economically during the first decade of colonisation, but as European population increased and settlement lands came into production, Māori contributions to the economy declined, exacerbated by alienation of customary lands, and legislation controlling Native Reserves. The final blow was Governor Grey’s 1853 transfer of 918 acres of the best Māori-owned horticultural land at Motueka to the Church of England for the Whakarewa School.

2008

Updated April 2020

Story by: Hilary and John Mitchell

Sources

- Wakefield A to William Wakefield (1.12.1842) MLS A3094-2 : Wakefield Papers qMS- copy -2099, Alexander Turnbull Library ; Mitchell, H&J (2007) Te tau ihu o te waka, v. 2. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatu Incorporation, p.243,

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Pratt, W. (1877) Colonial experiences, or, incidents and reminiscences of thirty-four years in New Zealand. London : Chapman & Hall, p. 51.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154471632; Mitchell, v 2. p.244. - Murray, H.N. (1966) Pioneer story of David and Jean Drummond. Committee of family descendents.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154575577; Mitchell v.2 253

Further Sources

Books

Published and unpublished sources about Maori and business:

Pre-settlement trade with Europeans:

- Mitchell, H & J (2004)Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A history of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, vol I: the people and the land. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatu Incorporation, pp. 155-157, 201-206, 211-212, 235-239.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610

Trade in colonial times:

- Barnicoat, J.W. (1843) Journal qMS typescript [NPM] ; [ATL]: Manuscript copy.

- Petrie, Hazel (2005). Bitter Recollections? Thomas Chapman and Benjamin Ashwell on Maori Flourmills and Ships in the Mid-Nineteenth Century? New Zealand Journal of History,39,1, p.1-21

- Petrie, Hazel. (2006). Chiefs of industry; Maori tribal enterprise in early colonial New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/86118192&referer=brief_results - Stanton, W. Notes on Nelson History: 6. Aborigines". Alexander Turnbull Library: Stanton Papers Micro MS 792+0772.

- Stephens, S: Letters and Journal. Nelson Provincial Museum: Bett qMS (4 volumes typescript)

- Mitchell, H & J: (2007)Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough" vol 2:, The new society. Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatu Incorporation, pp. 242-275.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/254390937&referer=brief_results

Crops:

- The first growers. (1993). New Zealand Commercial Grower, 48 5, p.7-9

- Statistics of Nelson 1846 (1847, 27 Mar) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18470327.2.7 - Statistics of Nelson 1847 (1848, 15 Jan) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18480115.2.9 - Statistics of Nelson 1848. (1849, 27 Jan) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18490127.2.7 - Statistics of Nelson 1849 (1850, 16 Feb) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18500216.2.6 - Statistics of Nelson 1850 (1851, 1 Feb) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18510201.2.8

Shipping:

- Nelson Provincial Government Gazette; Returns 1854.

Websites

- Mitchell, H. &. J. (2008) Commerce and Trade: Te Tau Ihu tribes. In Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 28-Oct-2008

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/te-tau-ihu-tribes/4

![Artist unknown :[Aorere, Golden Bay ca 1843].](https://backend.theprow.org.nz/assets/Maori/tradeAorere.jpg)