Karaitianatanga - Māori and Christianity

Christianity was brought to Marlborough as early as 1839

Māori had a complex system of faith and worship, not unlike Greek, Roman and Jewish traditions. Io, the Creator, was ‘... a primary core, heart, essence, who existed in space. He had no parents and was self-created'.1 The sons of Rangi and Papa, Tāne, god of forest, trees and birds, Tangaroa (seas and fish), Tumutaueka (war), Rongo (peace and agriculture), and many other gods were acknowledged and invoked when activities fell within their spheres. There were also tribal, district and whānau gods, and some deities appeared in natural phenomena like rainbows (Kahakura) or as incarnations (green lizards, frogs, owls, sharks). Concepts of wairua (the spirit), mauri (life-force of people, places and objects), hau (the breath, the vital element of human beings), and faith in an after-life underpinned these beliefs. Tohunga, often high-born, carefully selected and highly-educated, acted as mediums of the gods, interpreting signs, addressing the gods on the people’s behalf, and leading incantations, rituals, offerings and sacrifices; they were consulted on military strategies, horticulture, fishing expeditions, and health. Tūāhu, simple natural or constructed shrines, were used for ceremonies.

Anglican lay missionaries arrived in Northland in 1814, followed by Wesleyans in 1822, and Catholics in 1838. Māori were fascinated by the all-powerful God, and the Bible, full of wonderful stories, was key to the desirable new arts of reading and writing. Northern Māori quickly evangelised their southern relatives and friends. The Wesleyans, Bumby and Hobbs, visited Marlborough in June 1839 and discovered ‘... true light has shone teaching the people to observe the Sabbath and worship God which they do ... to the best of their ability twice a day'.

About 300 ‘chiefs, warriors, slaves, women and children' assembled to hear the missionaries at Tory Channel; some could read, and all were desperate for scriptures.2 Dieffenbach confirmed in August 1839 that Māori at Anaho/ Cannibal Cove (near Ship Cove) ‘... had lately become converted to Christianity by a native, who had been with the missionaries in the Bay of Islands', and that ‘Bukka Bukka' (the Bible in Māori, or white paper) were very desirable trade goods.

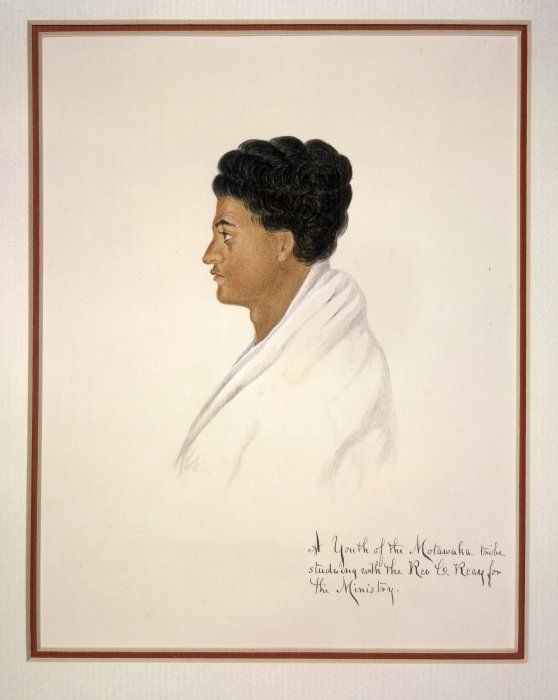

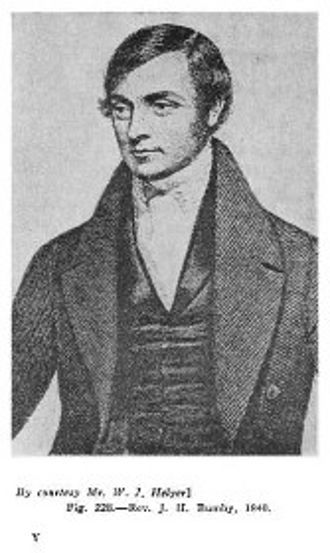

Octavius Hadfield, Church Missionary Society, who visited Marlborough and Nelson from Waikanae from 1839, teaching and baptising, reported a congregation of 900 at Okukari (outer Tory Channel) in July 1841. Samuel Ironside, Wesleyan, established himself at Ngakuta, Port Underwood, in December 1840. In two years he baptised 612 Māori adults, 155 infants, and married 171 couples; sixteen chapels were built and schools operated throughout Te Tau Ihu. Many Anglican and Wesleyan Māori became catechists.

Ironside's Marlborough congregation collapsed from 1,500 to six members when Ngāti Toa and Te Ātiawa returned to the North Island after the Wairau Affray in June 1843. In Nelson, ministers served both European and Māori flocks. Despite their initial commitment, Māori drifted from Christianity because of missionaries' roles in injurious land deals, church negligence caused by settler capture of clergy, and sectarian jealousies. Many years later Ironside reflected: ‘If the troubles and difficulties arising out of the colonising of the country could have been kept away, there would have been a noble, glorious Christian Church of Māoris, hardly inferior to any church on earth'.3

In the late 19th century many Te Tau Ihu Māori were re-evangelised by Mormon missionaries, or joined syncretic religions which fused Biblical ideas and traditional beliefs. A Ngāti Koata/Ngāti Kuia man from Pelorus, Haimona Patete, founded the Seven Rules of Jehovah church, which flourished in Marlborough and Wairarapa for about 25 years from the 1890s.

2010

Updated April 2020

Story by: Hilary and John Mitchell

Sources

- Buck, P. (1949) The Coming of the Maori. Christchurch, N.Z.: Whitcomb and Tombs. pp531-533

- Bumby, J. (1831) Journal. 25 April - 11 July .

- Ironside, S (1891) Missionary Reminiscences. V. In ‘The New Zealand Methodist 17 January . Wesleyan Archive, Morley House, Christchurch

Further Sources

Books

- Buck, P. (1949) (Te Rangi Hiroa) The Coming of the Maori. Christchurch: Maori Purposes Fund Board; [distributed by] Whitcombe and Tombs

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/760608 - Hadfield, O. Letters. Doc. No. qMS-0897-0902 Vol I. Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library

- Hadfield, O. To CMS. Doc. No. qMS-0895. Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library

- Ironside, S. (1891) Missionary Reminiscences. New Zealand Methodist, January-November Wesleyan Archives, Morley House, Christchurch.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/173322784 - Mitchell, H. A. & M. J. (2007) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, Volume II pp69-136.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/276659471 - Reay, C. L. Reports to Church Missionary Society. Doc. No. Micro-MS-Coll-04-08. Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library

- Reed, A. W. (1955) The Impact of Christianity on the Maori People. Wellington: A H & A W Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/2728060

Websites

- Stenhouse, J. 'Religion and society - Māori and religion', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. (accessed 6 April 2020)

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/religion-and-society/page-4