Mātauranga - Māori and education

Maori were keen to learn, but not at the expense of their language and culture

Pre-European Māori learned by oral methods which developed strong memory skills and powerful oratory. Early European visitors and settlers admired Māori intelligence. Dieffenbach (1839) wrote:

‘A desire of instructing themselves and a spirit of curiosity, pervade young and old. They are very attentive to tuition, learn quickly, and have an excellent memory ... in quickness of perception - they are superior in general to the white men ...' and noted that nothing escaped the children.1

Barnicoat described Māori as ‘... very adept at acquiring our language.'2 Stephens thought they ‘... mostly possess great natural intelligence' 3and Greenwood believed there was no ‘... more improvable people both as to capacity and disposition'.4

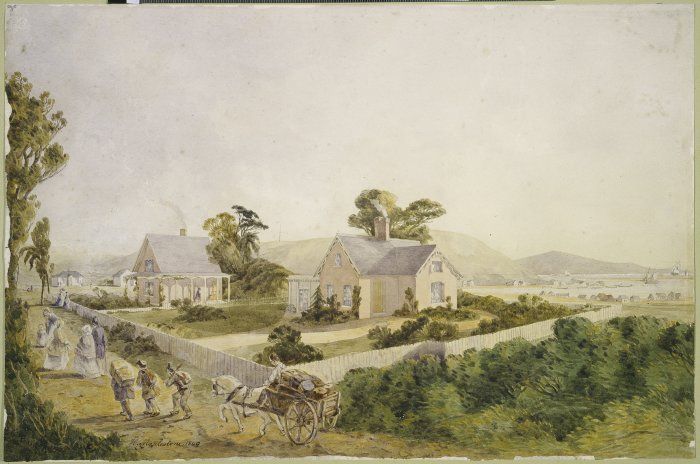

Literacy arrived in Aotearoa with early missionaries and Māori quickly learned to read and write in Te Reo. In 1839, before European missionaries or settlers arrived in Te Tau Ihu Crawford observed a wānanga (conference) at Anaho, near Ship Cove:

‘... we found the Maoris collected in groups around numerous fires, and very busy sending messages to each other on slates. The art of writing had just been introduced, and the Maoris seemed to have acquired a furor for it. They wrote everywhere, on all occasions and on all substances, on slates, on paper, on leaves of flax, and with a good, firm decided hand'.5

Four years later Barnicoat witnessed another class at Anaho:

‘At sunrise we heard the accustomed bell for service. About the whole population of this village, to the number fifty, attended. Immediately after the service the congregation formed themselves into two circles on the grass. One circle listened to a reader, the other had each a slate on which they wrote, and the writing was afterwards examined by a Native instructor and corrected'.6

In 1849 Bell, New Zealand Company Resident Agent in Nelson, regretted ‘... the rather humiliating fact of the mass of the natives near any settled place being far more proficient in these "simple accomplishments" [reading, writing and religious knowledge] than the European population'.7

Despite the great success of these self-instructing schools, a desire to ‘civilise' Māori by changing their language and their lifestyle caused European pressure for Māori to be educated in English. A boarding school to ‘... take children from their parents at as early an age as they can be induced to part from them, to give them an English education, and bring them up in English habits' 8 never opened because clergy could not get a single enrolment.9 In 1848 Rev. Tudor opened a school conducted in English at Motueka for both Māori and Pakeha; an inspection in 1852 found ‘... far more quickness of capacity for learning among the average of the native boys than with English boys of similar ages and standing. There is a vigour of intellect exhibited by the native scholars which is quite refreshing to witness'.10

This school was superseded by Governor Grey's grant of 918 acres of Māori land at Motueka to the Anglican Church for an industrial boarding school, Whakarewa. Whakarewa failed because Māori resented the high-handed alienation of their land, disliked separation from their children, disapproved of corporal punishment, and wanted full academic education, not thinly-disguised servant training.

Native schools, under an 1867 Act, opened at Wairau and Wakapuaka in 1874, and Waikawa and Pelorus in 1878. There was constant tension between the Government's desire to ‘civilise' Māori, and Māori desire to retain identity, Te Reo and tikanga, and the seasonal itinerant Māori lifestyle caused attendance problems. By the end of the 19th century few Māori were receiving any education, and Pakeha community schools were not welcoming. The Anglican Church opened schools at Whangarae, Croisilles Harbour (1898) and Okoha, outer Pelorus Sound (1900).

It appears that Māori were keen to learn, but not at the expense of their language and culture.

2010

Updated April 2020

Story by: Hilary and John Mitchell

Sources

- Dieffenbach, E (1843) Travels in New Zealand. Volume II. London: John Murray pp31, 108.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/181511432 - Barnicoat, J. (1842) Journal 18 August . Typescript copy. Nelson Provincial Museum.

- Stephens, S. (1843) Letters and Journals. 27 July. Typescript copy. Nelson Provincial Museum .

- Greenwood, J. D. (1843) Letter. November. Doc. No. qMS-0886. Wellington, NZ : Alexander Turnbull Library

- Crawford, J. C. (1880) Travels in New Zealand and Australia. Trubner and Co., London p31. In H A & M J Mitchell: TTIW2 p330.

- Barnicoat, J (1843) Journal 18 March. Typescript copy. Nelson Provincial Museum.

- Bell, C. D. Doc. No. MS-Papers-03-37:47. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

- Nelson Examiner: 15 April 1843.

- Stephens, S. (1843) Letter 29 September. Nelson Provincial Museum.

- Tuckett, F. Letter (1843) 12 April. Doc. No. MS 156 ++. Dunedin : Hocken Library

- Stephens, S. (1852) Letters and Journals. March. Typescript copy. Nelson Provincial Museum

Further Sources

Books

- Stack, J. (1875) Reports on Native Schools. In AJHRs: 1875 G-2A; 1876 G-2; 1878 G-7.

- Barrington, J. M. and Beaglehole T. H. (1974) Maori Schools in a Changing Society: an historical review. Wellington: NZ Council for Educational Research.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1443767 - Mackay, A (1873) A Compendium of Official Documents Relative to Native Affairs in the South Island. Vol II pp283-304, p308 re establishment of Whakarewa, and 1869 Enquiry re Whakarewa. Wellington : Government Printer

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/152475789 - Mitchell, H. A. and M. J. (2004) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough. Volume II pp329-346.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Openshaw, R., Lee, G and Lee, H. (1993) Challenging the Myths. Rethinking New Zealand's Educational History. Palmerston North, N.Z : Dunmore Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/31283376 - Simon, J (ed) (1998) Ngā Kura Māori The native schools system 1867-1969. Auckland, N.Z. : Auckland University Press.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/247650345