Pā and Kāinga

Ancient pa (fortified settlements) and kainga (villages) scatter Te Tau Ihu o Waka. European settlers certainly did not arrive in a "barren social and cultural landscape…"

Ancient pā and kāinga are scattered across Te Tau Ihu o Waka. European settlers certainly did not arrive in a "barren social and cultural landscape..."1

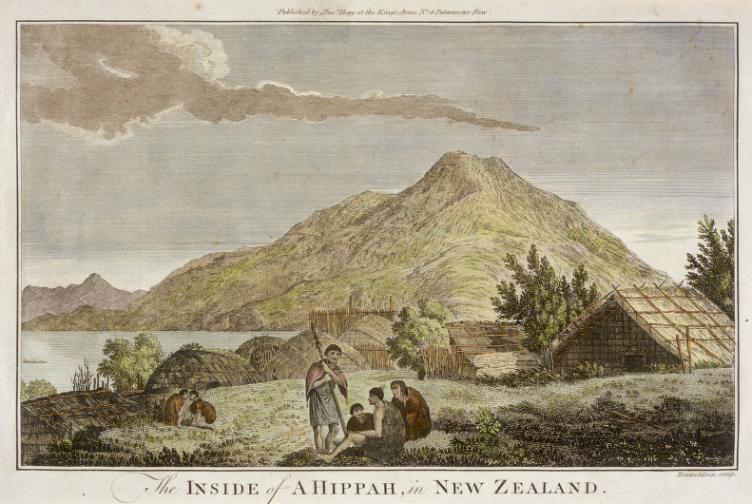

Māori lived communally, usually in kāinga or in fortified pā. In more settled times communities lived close to cultivations, tauranga waka, water supply, and food and other resources (in rivers, estuaries, forests and the sea). When their security was threatened they resorted to pā, on sites chosen for their view of the surrounding countryside and/or sea, their defensibility, and their strategic value. Access to food, water, and waka transport was still important, but adaptations, such as storage pits for food and waka hulls to collect water, could be made.

There were various reasons why pā or kāinga could be left to decay. Habitations taken in battle might be occupied by the victors, or they could be left deserted and a new settlement created some distance away. A whole village could be abandoned and declared tapu on the death of a chief of high mana, and some actions or events warranted the burning of houses. Long-abandoned ancient pa sites are still known through oral tradition and archaeology.

A strong characteristic of traditional Māori lifestyle was its mobility. Whole communities would move for harvests at certain times of the year, for fishing and hunting seasons, for planting crops (sometimes at a better location), for whānau or political reasons, and, of course, because of conflict or scarce resources. The customary practice of whakarahi to maintain ahi-kā-roa , and to confirm tribal dominance of territories, was expressed through this itinerant lifestyle.

As European visitors arrived, and whalers took up at least seasonal residence, Māori often shifted to be close to trading opportunities. The missionary base of Rev. Samuel Ironside at Ngakuta, Port Underwood, influenced residential patterns, and the great influx of New Zealand Company settlers from 1842 caused further moves, so that Māori could take advantage of the new economy.

At the time of European settlement, major Māori communities of Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Rarua, Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Koata and Ngāti Tama were recorded at:

-

several pā near the mouth of the Wairau River

-

a number of bays in Port Underwood close to onshore whaling stations

-

almost every bay in Tory Channel (another whaling base), and Moioio Island

-

various sites on Arapaoa Island

-

Waitohi (Picton)

-

many bays throughout Totaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound) from Anakiwa to Port Gore

-

a number of sites in the Pelorus Valley and Sound to as far out as Titirangi on the southern coast of Cook Strait

-

Rangitoto (D'Urville Island) several

-

Whangarae (Croisilles)

-

Motueka (with an estimated population of 500 Māori)

-

Marahau

-

Whariwharangi, Taupo, and three sites at Wainui

-

Tata, Ligar Bay, Pohara, Motupipi, and Takaka

-

Pariwhakaoho, Tukurua, Parapara

-

Aorere (Collingwood)

-

Tomatea, Pakawau, Te Rae

-

West Whanganui and Te Tai Tapu (three sites).

There were also small groups of Kurahaupo people at Waihopai, Kaituna, Pelorus and near Wakefield. Rangitāne lived with Ngāti Toa and Ngāti Rarua at the Wairau.

Many of these locations were set aside as Occupation Reserves for the inhabitants when land was purchased by the New Zealand Company or the Crown.

2008

Updated April 2020

Story by: John and Hilary Mitchell

Sources

- Mitchell, H&J (2007) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough" Vol II, p20.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610

Further Sources

Books

- Alexander, D. (1999) Reserves of Te Tau Ihu. Two volumes, Wellington :Waitangi Tribunal

- Best, Elsdon (1916) Maori storehousesand kindred structures : houses, platforms, racks, and pits used for storing food, etc.Wellington, N.Z.: : A.R. Shearer, Govt. Printer, 1974

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/2376201 - Brailsford, B. (1981) The tattooed land. Wellington : Reed

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8356281 - Davidson, J. (1987).(2nd ed) The Prehistory of New Zealand. Auckland: Longman Paul.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/12103496 - Dieffenbach, E (1843) Travels in New Zealand, vols 1&2. London : John Murray.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5739675/editions?editionsView=true&referer=di - Earp, G.B. (1853, reprint 1998) Hand-book for intending emigrants to the southern settlements of New Zealand : including a section on New Zealand and its emigration and gold field . Christchuch [N.Z.] : Kiwi Publishers.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/155557483 - Hodder. E.(1862) Memories of New Zealand Life. London: Longman Green.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28030784 - Mackay, A (1873) Compendium of official documents relative to native affairs in the South Island, 2 volumes. Wellington : Government Printer. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154076706

- Mitchell, H & J: (2007) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough" Vol II The new society Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers/ Wakatu Inc. pp20-67 and references cited there.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 [For an account of traditional Maori village lifestyle see Mitchell H&J, Vol II pp16-19.] - Mitchell, H & J (2009) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough. Volume 3, Nga tupuna = the ancestors. Wellington, N.Z. : Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatū Incorporation

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/773197494 - Roberts, WHS (1912) Maori nomenclature; early history of Otago Dunedin : Otago Daily Times & Witness

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45411776/editions?editionsView=true&referer=di - Salisbury, J.P. (1907) After many days: an account of New Zealand experiences. London: Harrison & Sons

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154173371 - Wakefield, E.J. (1845) Adventure in New Zealand. 2 volumes London: John Murray.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8558703/editions?editionsView=true&referer=di - Ward, J (1840) Supplementary information relative to New Zealand. London : J.W.Parker

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/187446338

Newspapers

- Domett, A.(1.10.1842; 8.10.1842; 22.10.1842; 19.11.1842; 3.12.1842) Notes of an expedition to Massacre Bay. Nelson Examiner

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/nelson-examiner-and-new-zealand-chronicle - Parker, E. (1989) Recollections of earlier days in Motueka. Journal of the Motueka & Districts Historical Association, 5, pp49-56

- Stephens, S. (1845, March 29) Sketch of an excursion from Nelson. Nelson Examiner

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18450329.2.3 - Tuckett, F (1842) Report of an examination of the shores and lands adjacent at Massacre Bay.....New Zealand Journal, 258-259 and Nelson Examiner (1842, April 16)

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18420416.2.10 - [Waimea Plains Maori] (1842, April 9) Nelson Examiner

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18420409.2.3

Websites

- Basil Keane. 'Te hopu tuna – eeling - Cooking, preserving and storing eels'. Retrieved November 30, 2009, from: Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 2-Mar-09 http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/te-hopu-tuna-eeling/7

- Best E. (1941) XV The Pa Maori or Fortified Village. In The Maori, volume 2. retrieved from NZETC:

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-Bes02Maor-t1-body-d7.html - Manuka Henare. 'Te mahi kai – food production economics - Types of food production'. Retrieved November 30, 2009, from: Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 1-Mar-09

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/te-mahi-kai-food-production-economics/3 - Moore, Tinuku (1959) How our great grandparents lived,.Te Ao Hau: the new world, No.26, 10-11. Retrieved November 30, 2009 , from: National Library of New Zealand Te Ao hau website.

http://teaohou.natlib.govt.nz/journals/teaohou/issue/Mao26TeA/c8.html - The Pa : Maori material culture (2008) An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock(1966) Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand :

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-material-culture/10

Maps

Unpublished sources (NPM= Nelson Provincial Museum; ATL = Alexander Turnbull Library; MM = Marlborough Museum)

- Barnicoat, J.W. (1843) Journal qMS typescript [NPM] ; [ATL]: Manuscript copy.

- Brunner, T (1848) Daily Journal. UMS Typescript [NPM]

- Campbell, A. Daily Journal and sketchbook. UMS 37: CAM [NPM]

- Eyles, J. Papers. [NPM]

- Reay, CL Church Register of Population. MS Papers 1925:54/5 [ATL]

- Tucket, F (27.4.1843) Diary, Hale Clearfile V9, 42d-f [MM]

- Simmonds, J. Narrative of events in the early history of Nelson, New Zealand. qMS: SIM [NPM]

- Stephens, S. Letters & Journals. [NPM] Bett qMS (4 vol typescript)

- Wakefield, A. (1841-42) Diary. qMS NZ Co. Papers. Bett Collection [NPM]

- Weld, F (n.d.) Diary and letter extracts. In Marlborough Express. Hale Clearfile vol 10: 129 [MM]

![Messenger, Arthur:Taupo [Pa], Massacre Bay. 1921 [i.e 1844]](https://backend.theprow.org.nz/assets/Maori/Taupo-pa.jpg)