Mōkai - Slavery in Colonial Times

As in many other cultures, slavery was a key element of Maori society.

As in many other cultures, slavery was a key element of Māori society. Mōkai (servants or slaves) were usually spoils of war, condemned to lives of drudgery, danger, heavy physical work and obedience to their masters or mistresses' whims; they were expected to fight under supervision, could be used to negotiate with enemies, or as food if supplies were short. Female slaves might be prostitutes, or become secondary wives to their conquerors. Marriages between victorious chiefs and highborn women of defeated tribes strengthened the invaders' right to the land.

The Treaty of Waitangi, 1840, outlawed the taking of slaves, and made all Māori British citizens, but did not affect pre-Treaty arrangements. Christianity preached the equality of all before God and some slaves were freed as a result. In other cases masters and slaves were baptised together, but existing relationships prevailed. One of Rev. Ironside's best local preachers was Paramena, a slave who experienced some prejudice in his leadership role.1

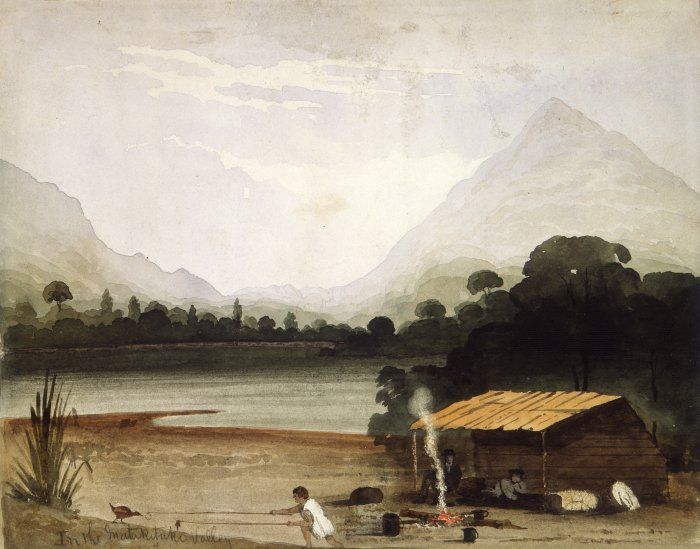

Some chiefs had many slaves, and mōkai appear frequently in colonial records: accompanying masters, carrying goods or gifts, doing menial tasks and obeying orders. Chiefs hired slaves to European explorers and surveyors: Kehu and Pikiwati, Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri slaves of Ngāti Rarua chiefs, guided Brunner on his West Coast expedition (1846-1848). Tau, Ngāi Tahu slave of a Te Ātiawa chief, had accompanied Brunner, Heaphy and Kehu on their earlier 1846 journey. They all returned to their masters.2

Slaves were sometimes restored to their people: Paremata Te Wahapiro of Ngāti Tama, captured by Ngāi Tahu at Tuturau in 1837, was delivered back to Wakapuaka with a new wife, daughter of his captor, Taiaroa;3 Ngāti Toa returned Ngāi Tahu chiefs to Kaikoura or Banks Peninsula in about 1840;4 and a party of Ngāi Tahu made their way from Motueka to Lyttelton in two large boats in 1851.5 A few slaves escaped to become fugitives.

Some chiefs formed strong bonds with mōkai. Paremata wanted to support his mōkai, arrested in 1843, until deterred by Europeans;6 Panakenake and Poria, Kehu's chiefs, gave him a life-time interest in land at Motueka,7 and Ngarewa, Te Ātiawa chief at Port Gore, insisted Government agents allocate land for his Ngōti Apa slaves.8 Bishop Selwyn was amazed when one of his staff tried to purchase the release of his mother and brother from a chief at Croisilles. The mother refused to leave - "she loved her master" and would "not go out free".9

While there are accounts of very brutal treatment of slaves in pre-colonial times,10 the lack of criticism after 1840 suggests that officials, clergy and settlers were not offended by what they saw. Rangatira continued to own slaves well into the 1850s and perhaps later. Europeans supported the system by acknowledging the existence of slavery, and hiring slaves from chiefs; Sarah Ironside (wife of Samuel Ironside), home alone after the Wairau Affray, in order to retain the services of her domestic help, gave a "pair each of our largest and best blankets" to their chiefs who were leaving for the North Island.11

In general, slaves were keen converts to Christianity, no doubt attracted by its benefits to them and, as their masters' control decreased, often worked for Europeans who paid them for tasks they formerly did for nothing.12

The passage of time eventually led to the extinction of slavery.

2010

Updated April 2020

Story by: Hilary and John Mitchell

Sources

- Ironside, Rev. S. (1842) Journal, 7 November. Wesleyan Archives, Morley House, Christchurch.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2007) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Māori of Nelson and Marlborough, Volume 2, Te ara hou : the new society. Wellington, N.Z. : Huia Publishers pp276-289.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2004) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Māori of Nelson and Marlborough, Vol I, The People and the land. Wellington, N.Z. : Huia Publishers p137.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2004) p 130.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2007) p 196.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2007) p 455.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2007) p 456.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2007) p 455.

- Selwyn, G (1848) to Hawkins. 30 August, In "New Zealand" Pt IV 1847 pp62-63.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2004) pp 452-453.

- Ironside, S: "Missionary Reminiscences" VIII & XIV. 1891. Wesleyan Archives, Morley House, Christchurch.

- Mitchell, H.A., & Mitchell, M.J. (2004) pp192-199.

Further Sources

Books

- Mitchell, H.A & M.J (2004) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, Vol I The People and the land. Wellington, N.Z. : Huia Publishers

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Mitchell, H.A & M.J (2007) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough, Volume 2, Te ara hou : the new society. Wellington, N.Z. : Huia Publishers

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/276659471

Newspapers

- Vayda, A.P. (1961) Maori Prisoners and Slaves in the Nineteenth Century. Ethnohistory, 8(2), pp. 144-155

Maps

-

Ironside, Rev. S. (1842) Journal, 7 November. Wesleyan Archives, Morley House, Christchurch

-

Ironside, S: "Missionary Reminiscences" VIII & XIV. 1891. Wesleyan Archives, Morley House, Christchurch