Ngawhatu Hospital

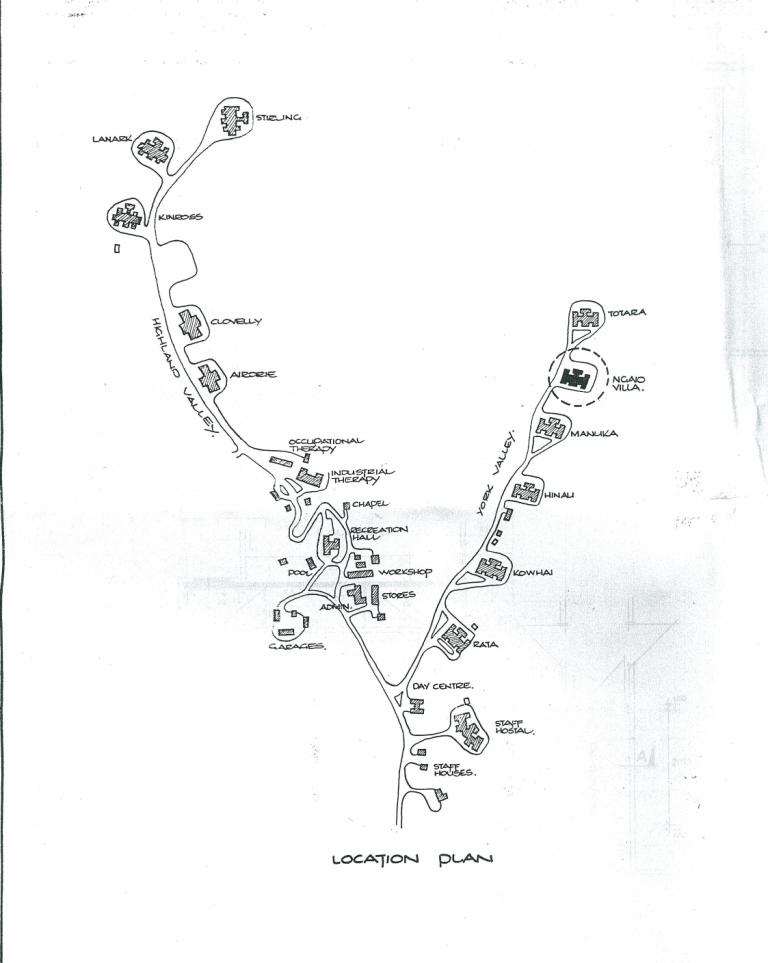

Ngawhatu Hospital… Home or nightmare? Ngawhatu Valley was the site of an orphanage, industrial school, and later a psychiatric hospital. St Mary's Orphanage operated from 1886-1919. Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital operated from 1922 to 2000. Plan of Ngawhatu. Alan Dalzell 1989.

Ngawhatu Hospital… Home or nightmare?

Ngawhatu Valley was the site of an orphanage, industrial school, and later a psychiatric hospital. St Mary's Orphanage operated from 1886-1919. Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital operated from 1922 to 2000.

Walking up the sloping, never ending driveway at the end of Ngawhatu Valley, 2011, sent shivers down my spine. Gigantic trees loom overhead forming a dark tunnel. Trying to imagine what it would have been like to live so isolated from the public is simply impossible. Hastening up the driveway one suddenly catches a glimpse of a single, poorly kept, condemned old villa. Fifty metres down the drive one sights another, the remaining two skeletons of the past. The eerie atmosphere creates a chilling stillness. Black holes replace the smashed windows of a hidden room on the inaccessible second level. Something stirs in the shrubbery; one imagines the worst and escapes from these ‘ghost houses’. Visiting these buildings is a nightmare in the daytime, so how could these aged buildings in the tranquil valley have been home for so many years?

A rather small house in Shelbourne Street, Nelson, acted as a home to nine mentally ill patients in 1861.1 An ‘asylum’ was an institution for the care of the mentally ill. This could not possibly be home… Nelson was increasing rapidly in population. With more and more mentally ill people seeking treatment, the undersized house on Shelbourne Street could no longer suffice for the growing numbers. A larger site with more space was needed to treat the mentally ill. In 1920, the government bought some property that had potential for a psychiatric hospital, deep in the heart of the dense, eerie Ngawhatu Valley.

The building of the new ‘loony bin’ was finished and by 1922 it was running smoothly enough for a newly opened hospital. The psychiatric hospital at Ngawhatu Valley filled up quickly with patients, young and old, ranging from epileptic to schizophrenic. Individual female and male villas were viewed as too segregated for a hospital. In 1984, as a result of a government plan, the individual female and male villas were integrated to house larger groups of mixed gender.

The closure of the Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital, amid claims of patient abuse, came as little surprise in the year 2000. New Zealand had more people per head of population in institutions than anywhere else, which was rather disturbing. Mark Nalder, a registered psychiatric nurse who worked in all areas of Ngawhatu hospital, said “Ngawhatu was growing at an alarming rate.”2

By the 1950s/60s, worldwide, people were thinking of better ways to treat the mentally ill rather than by isolation. It was no longer seen as acceptable to keep people in such isolated environments. Society had started to change its views of mentally ill people in the community. The fact that people were, or became, mentally ill was seen to be a part of life that couldn’t be changed and society was beginning to embrace this. With people’s views changing, the process of closing Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital began in the late 1990s. Martin Anderson worked at Ngawhatu as a project manager for intellectually disabled people, by managing the movement of these people from Ngawhatu hospital to community living. He commented that he thought the closure was due to increasing evidence, and emerging philosophies around the world, that institutions denied people basic human rights and being part of the community. While it would be more expensive to have patients living in the community, it meant people would receive better social and health outcomes.3

The hospital and surrounding property were sold in 2001. Today there are only two villas left standing and they have been condemned. When it was operating as a hospital, Ngawhatu was a solid mental institution functioning efficiently for the time. The way patients were treated there between the years 1922-2000 at Ngawhatu was a lot different to how patients at the Wahi Oranga Mental Health Unit are treated today. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) was probably the most widely used and recognised treatment associated with psychiatric hospitals. By the mid 1980's it was used in a more targeted manner to treat specific psychiatric illnesses.4 Ngawhatu believed in the use of drugs, individual counselling sessions and group therapy, much of which are similar treatment procedures to those used today. The time patients spent at Ngawhatu was, however, longer than today (usually months) depending on their conditions.

Mr Anderson believes the treatment of patients at Ngawhatu was generally good, but he also commented that the recognition of issues of informed consent and patient rights could have been improved. He had occasionally seen firsthand some patients being deprived human rights: “There were times at Ngawhatu when people were given treatment without due regard to consent or patient rights. Simple things like being asked ‘do you want something for the pain’ – often drugs would be given to the patients without such questions being asked.” 5 Nathan Davis, who worked at Ngawhatu for three years in the mid 1990's, said that Wahi Oranga is now more focused on helping mentally ill patients without the side effects of drugs.6

Nurses' treatment of patients at Ngawhatu was challenging, as there were large patient numbers and few staff . One psychiatric nurse, Suzanne Win who worked at Ngawhatu, recalled a time when; “Staffing was tight; an example was 4 staff to 50 patients in one villa, therefore meaning nurses worked very hard.”7 In 1971, the nursing staff was 164 and patients 641 (excluding 61 on leave).8 This shows just how difficult the conditions must have been compared to 2011 (there is capacity for 31 patients at the NMHU).

The housing of patients throughout their treatment at Ngawhatu was by a villa system. The villas operated as homes to numerous people. Most of these people did not have a choice about where they lived, as they were ill and needed the specialised treatment Ngawhatu provided to get well again. However, “Some people who enter Ngawhatu voluntarily may still become quite ill, perhaps even suicidal.”9

There were 13 villas, each housing between 40-60 people. The villas often got rather crowded, especially Rata villa. Rata had 23 beds and even with that amount, some patients had to sleep on mattresses on floors in offices.10 The villa system gave the patients more personal freedom and trust, however it was also a much less private way of living: it must have been a nightmare to have to wash in the same open showers as all the other patients. There were four open showers and two baths in the middle of one room. Nathan Davis observed; “Staff did not think they needed much privacy, they were there for treatment not for ‘homely’ living.”11

Something else that has changed considerably is the outdoor environment. Ngawhatu provided park-like surroundings. There were large amounts of free space outside in the ‘beautiful gardens’'12 for patients to do activities such as golf, tennis and croquet. These park-like surroundings Ngawhatu offered are not seen now - but patients are in residence for a much shorter time.

Being labelled a mental institution, we automatically imagine locked doors and big keys jangling off a warden’s belt, however, Ngawhatu was not like this. The patients were not locked in; instead the hospital was secluded down a deep twisting valley road that was far away from town and civilisation.

Mr Davis spoke of the differences between Ngawhatu and care of patients today. When he was a student nurse, Ngawhatu did not just accommodate people with mental illnesses and disorders, it also catered for developmental disorders, older patients with disorders that had developed over the years and dementia. People whose mental illnesses meant they could not live independently were cared for by Ngawhatu. 13

Today, there are houses available in the community that cater for specialist placements, provided by supported accommodation providers Mental Health Support Services (MHSS) and Gateway Housing Trusts.

Rata villa took care of the acute admission and discharge into and out of the community. These were people who stayed at the hospital for a shorter period of time or for intensive treatment before being resettled back into the community. Rata villa’s patients were directly transferred to the Nelson hospital site after the closure of Ngawhatu. The placement from Rata villa is very similar to placements from NMHU now, with comparable medication approaches, individual talking therapy, group activities, shopping and life skills support, for example cooking. This is the unit Mr Davis managed in the position of charge nurse.15

Despite the apparent eerie atmosphere surrounding the remnants of the Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital today, in 2011, it was once a home to many ill people and those with special needs. The mentally ill are no longer isolated in secluded sites, which makes a big difference to how society both treats and views them.

Story written by Catherine Thomas, Nelson College for Girls, 2011

Updated: April 2025

Story by: Catherine Thomas

Sources

- Low, D.C. (1973). Salute to the scalpel. A medical history of the Nelson Province, etc. Nelson, N.Z.[medical superintendant at Ngawhatu]

- Nalder, M. personal communication 24/05/2011

- Anderson, M. personal communication 24/05/2011

- Manning, David (1985, November 9) Ngawhatu – an open door to mental care, Nelson Evening Mail

- Anderson

- Davis, N. personal communication, 31/05/2011

- Win, S. personal communication 27/05/2011

- Low

- Manning

- Collett, Geoff, (2000, 1 July) Ngawhatu bids farewell, Nelson Mail

- Davis

- Low

- Davis

- Arnold, N. (2009, 3 October) Moving on, Nelson Mail

- Davis

Further Sources

Books

- Low, D.C. (1973). Salute to the scalpel. A medical history of the Nelson Province, etc. Nelson, N.Z.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/salute-to-the-scalpel-a-medical-history-of-the-nelson-province-etc/oclc/560833290 - Webby, Majorie M. (1991). From prison to paradise - genealogy of Ngawhatu Hospital previously known as Nelson Lunatic asylum 1840-1991 and St Mary's Orphanage of Stoke. Nelson,N.Z.: The Author

http://www.worldcat.org/title/from-prison-to-paradise-genealogy-of-ngawhatu-hospital-previously-known-as-nelson-lunatic-asylum-1840-1991-and-st-marys-orphanage-at-stoke/oclc/156415681

Newspapers

- Arnold, N. (2009, October 3). Moving on. Nelson Mail, The.

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/features/weekend/2928408/Moving-on - Bale, R. (2002) An experience of New Zealand psychiatry. The Psychiatrist, 26, pp.192-3

http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/26/5/192.full - Calcott, D. (2007, October 4). Sex abuse claims. Press, The. p. A4.

- Collett, Geoff (2000, July 1) Ngawhatu bids farewell The Nelson Mail

- Health in Nelson on $1.43 a day (1983, March) New Zealand Hospital, p.10-16. (includes information on Braemar Hospital patient numbers at the time)

- Long, J. (2016, November 14) Inferno destroys 87-year-old Nelson building at Ngawhatu. Nelson Mail on Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/news/86422462/inferno-destroys-87yearold-nelson-villa - Man admits earlier false complaints of sex abuse (2007, October 4) Nelson Mail. Retrieved 13/05/2011 from Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/25222 - Manning, David (1985, November 9) Ngawhatu-an open door to mental care.Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu – Modern Home of Healing In Peaceful Valleys (1967, October 14) The Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu: 637 Patients and 150 Nursing Staff (1971, July 2) Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu part of damning report (2007, June 29) Nelson Mail, The p. 1.

- Shaw-Miller, N. (2013) History and memories of Braemar Hospital. Nelson Historical Journal, 7(5), p.48

Websites

- Ngawhatu from the air (1970, October 17) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN120_19701017/t1-body-d20.html#NPN120_19701017_025a - Ngawhatu (1961, October 14) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN12_19611014/t1-body-d10.html - Ngawhatu: a leader in the field (1971, June 26) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN128_19710626/t1-body-d20.html - Inferno destroys 87-year-old Nelson building.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/news/94056153/blaze-guts-abandoned-ngawhatu-psychiatric-hospital

Maps

Interviews

- Mark Nalder, Service Manager, Physical Disability Support Services, Intellectual Disability Support Services, Nelson Marlborough Health Services via email, 24/05/2011 [was manager of Totara Villa at Ngawhatu and project manager for NMHDB of "Ngawhatu Deinstitutionalisation of people with an intellectual disability"]

- Martin Anderson, Present: Self employed, Owner/Manager of Martin Anderson Consultants, via email, 24/05/2011 [worked on project to close Ngawhatu and move patients into the community]

- Robyn Byers, Nelson-Marlborough Mental Health Services Manager, via email, 27/05/2011

- Suzanne Win, Present: Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Development, National and Regional Non Governmental Organisations, Ministry of Health, via email, 27/05/2011 [worked at Ngawhatu as aid, trainee, staff and charge nurse for 15 years]

- Nathan Davis, Unit Manager, Acute Mental Health Admission Unit, Adolescent, Adult and Intensive Care, via email and telephone, 31/05/2011 [worked at Ngawhatu as student nurse 1994-97]

Archives

- Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital 1922-2000. Archway Agency:

http://archway.archives.govt.nz/ViewEntity.do?code=AEJU

Plan of Ngawhatu. Alan Dalzell 1989.

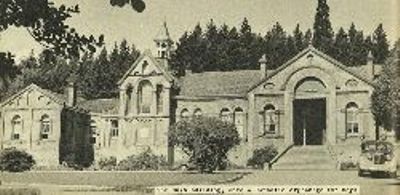

Plan of Ngawhatu. Alan Dalzell 1989. The main building, once a Catholic orphanage for boys. Nelson PhotoNews (1961, October 14)

The main building, once a Catholic orphanage for boys. Nelson PhotoNews (1961, October 14) The villa, Dunoon, for male patients Nelson PhotoNews (1961, October 14)

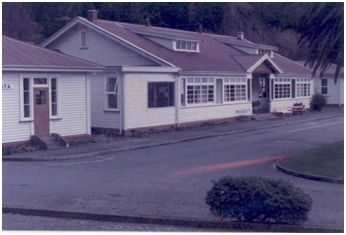

The villa, Dunoon, for male patients Nelson PhotoNews (1961, October 14) Ngawhatu's Rata villa. Image supplied by author

Ngawhatu's Rata villa. Image supplied by author Ngawhatu today. Image supplied by author

Ngawhatu today. Image supplied by author