Frederick Trolove

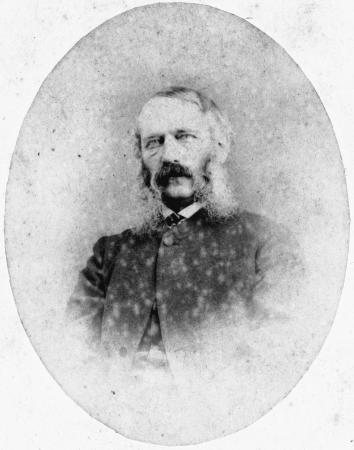

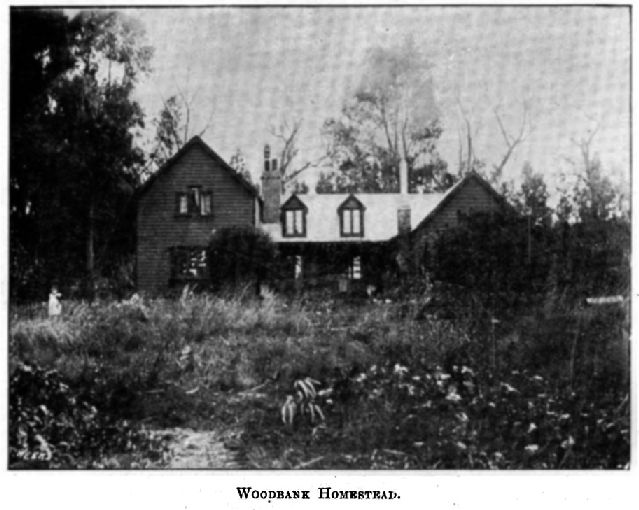

Trolove of the Clarence Frederick Trolove (1831-1880) was an early European settler who established Woodbank Run, located north of the Clarence River. Most of what is known about Trolove, comes from his letters (which can be found at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington).

Trolove of the Clarence

Frederick Trolove (1831-1880) was an early European settler who established Woodbank Run, located north of the Clarence River. Most of what is known about Trolove, comes from his letters (which can be found at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington). These give us a fascinating window into the life and experiences of an early Marlborough pioneer.

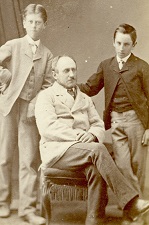

Trolove was one of four brothers who had a wealthy uncle, Dr John Shaw, of Boston, England. He was keen for one of his nephews to help him develop a sheep farming venture in the new colony of New Zealand. Frederick and his uncle arrived in Nelson in 1850 and took up a 42,000 acre run in the upper Awatere Valley. Dr Shaw returned to England, satisfied at the thought of a half share in a large sheep run. Lonely and isolated, Frederick was able to swap the run for land on the East Coast north of the Clarence River. He moved to the place he named Woodbank in about 1852 and was joined by his brother Edwin the next year.1

The terms of the contract signed in 1851, were that Trolove was to send his uncle in England a set amount of wool per year, and his uncle would supply start-up funds and cover up to half of any potential loss of income.2

In the summer of 1855, an 8.1 earthquake tore through Marlborough. Trolove described it thus: ‘a most awful shock the imagination could conceive forced us once more out of the house in the greatest confusion and alarm’. His cottage was ruined and at some point in the following decade, he returned to England.3

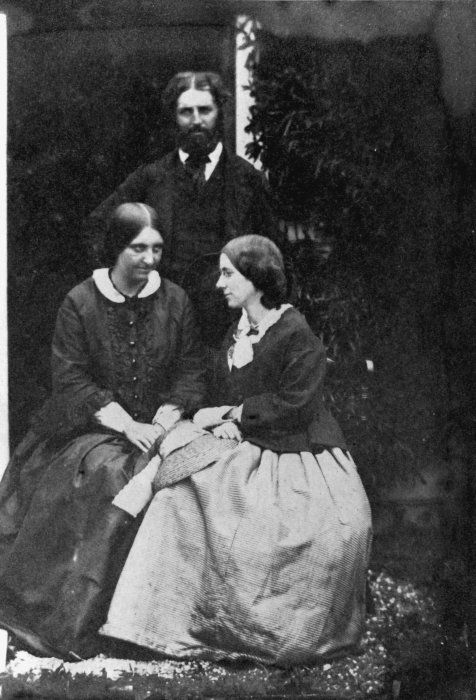

Trolove stayed there until 1866, when he wrote to his friend Nathaniel Levin of Wellington expressing concern about an outbreak of Rinderpest and the rumblings of a potential Fenian uprising in Ireland. His wife Mary was very ill, but seemed to be recovering – he planned to return to New Zealand as soon as she was well enough to travel: “I am glad to say that Mrs. Trolove is much improved in health since my last communication and should she continue to keep well, we intend making a start for New Zealand this summer.”4

He arrived in Wellington with his family in December,1866 and returned to Woodbank Run. His experience at sea was deeply unpleasant, and his wife and sons became ill. On arrival in New Zealand, he wrote “I hope never to put my foot on board an emigrant ship again, the miseries of the past 5 months have been unexampled.” 5

Trolove met with Levin and Joseph Tetley – a well-regarded landowner who was also in business with Levin. Trolove warmed to Tetley immediately, and took advice from him on the business of farming: it seemed the price of wool was dropping rapidly. Trolove wrote to his uncle and suggested selling all their sheep, and renting out the land. His uncle disagreed – their contract was for wool, and it would remain for wool. Despite the market slump, Trolove did good business for two more years, with the help of Messrs Levin and Tetley.

Tetley’s wife died in 1868, and he returned to England for the funeral. While he was away, Levin and others realised that Tetley was a conman, who had absconded with over £40,000. As the scandal unfolded over the next two years, Trolove discovered that he had lost £1,800 and 1,900 sheep. He wrote to his uncle and asked him to fulfil his side of the contract, and cover half the loss. His uncle refused. 6

Indeed, the uncle wrote back to Trolove in early 1870 and apparently accused him of “subterfuge [...] wicked evasion of the terms of agreement”. He didn’t believe the news of Tetley’s con, and still wanted the 9,000lbs of wool he was owed for that year.7 Trolove struck back in September 1871, saying in no uncertain terms that he could not send his uncle the wool and still service his new debts sustained in the deception.8

Although many of the victims of Tetley’s con turned on Nathaniel Levin, Trolove did not. He remained a loyal client of Levin’s for the rest of his life.9

Using the wool intended for his uncle and with some help from the bank, Trolove managed to right his accounts. When Trolove announced his intention to sell Woodbank Run to square the rest of the debt, his uncle responded tersely but positively, and Trolove wrote back “for more than 20 years I have been trying to do my duty to you, and never before have I received any token of your appreciation. I need not say how grateful I am to you for having at length written me these lines.”10

As he was developing the potential of his land, on May 29th 1872 he wrote to Marlborough’s superintendent, Arthur Seymour, to save the job of a Clarence River ferryman, and to secure more funds to replace the dilapidated ferry. His letter read “The boat is old & rotten & cannot be repaired […] I fully see the almost necessity of keeping Tyford as Ferryman inasmuch as he has hitherto proved himself quite competent & moreover he has the confidence of the public.”11

By 1876, the flow of letters between uncle and nephew had slowed. Trolove was in the black again, making good money selling wool. His wife Mary had established a trust under her will, to fund the Picton choral society. Trolove wrote to the trustees, asking them to buy a new harmonium for the church.12 He had earlier written to them “I have a strong repugnance for any instrument save the harmonium or organ.”13

Although his life was difficult, Frederick Trolove remained a hard-working and devout man. He twice pulled himself back from nothing, and left a lasting legacy. Trolove descendants live in the area to this day

2017

Updated August 2020

Story by: Alexander Stronach

Sources

- Kennington, A.L. (2007) The Awatere: a district and its people Christchurch, N.Z. Cadsonbury Publications p. 81

- Trolove, Frederick William, 1831-1880: Letter Book. September 12th 1871.

- Stephens, J. (2017) Life on the fault lines. The Prow

- Letter Book. July 1866.

- Letter Book. December 31st 1866.

- Letter Book. July 28th 1869.

- Letter Book. February 15th 1870.

- Letter Book. September 12th 1871.

- Letter Book. 1872.

- Letter Book. 1873.

- Letter Book. May 29th 1872.

- Letter Book. 1876.

- Letter Book. June 14th 1871.

Further Sources

Books

- Buick, T.L. (1900, 1976) Old Marlborough. Palmerston North, NZ: Hart and Keeling http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7342837

- Grapes, R & Downes, G. The 1855 Wairarapa Earthquake: Analysis of historical data (retrieved 9/6/17)

http://www.nzsee.org.nz/db/Bulletin/Archive/30(4)0271.pdf - Grapes, R. (2000) Magnitude eight plus. Wellington, N.Z.: Victoria University Press, 36, 83-9.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/magnitude-eight-plus/oclc/489031353 - Kennington, A.L. (2007) The Awatere: a district and its people Christchurch, N.Z. Cadsonbury Publications p. 81, 82, 215.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/awatere-a-district-and-its-people/oclc/810443357 - Kennington, A.L. (1968), The Anglican church in the Awatere: a parish history. Blenheim, N.Z.: N.Z. Express Printing Works, p. 7.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/anglican-church-in-the-awatere-a-parish-history/oclc/14135246 - Kennington, A.L.(1972, October) Flaxbourne-Kekerengu: Field day. Blenheim, N.Z.: Marlborough Historical Society.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/152405869 - McIntosh, A.D. (1977). Marlborough: a provincial history. Christchurch, N.Z.: Capper Press, p. 412.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/marlborough-a-provincial-history/oclc/19004291 - Newton, Peter. (1973) Big country of the South Island. Wellington: A H & A W Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/big-country-of-the-south-island-north-of-the-rangitata/oclc/469935326 - Sherrard, J. M. (1966) Kaikoura: a history of the district. Kaikoura, N.Z. : Kaikoura County Council p. 100-2, 105, 136-7, 151, 153-4, 160, 288, 297.

https://www.worldcat.org/title/kaikoura-a-history-of-the-district/oclc/810912347

Newspapers

Papers Past

- Advertisements(1859, 11 March). The Colonist, p. 2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC18590311.2.5.2? - Correspondence. (1856, 5 January) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p. 4.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18560105.2.12?query=trolove - Correspondence (1868, 1 August). Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p. 3.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18680801.2.13?query=trolove - Death notice (1867, 11 July). Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p. 2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18670711.2.7?query=trolove - Election of two members to represent the Wairau in the Provincial Council (1853, 13 August) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle,p.7.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18530813.2.20.3?query=trolove - The pastoral lands of Marlborough Province (1865, 29 August). The Colonist, p. 2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC18650829.2.10?query=trolove - Supreme Court (1869, 25 November). The Nelson Evening Mail, p. 2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18691125.2.9?query=trolove - Supreme Court (1869, 26 November).The Nelson Evening Mail, p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NEM18691126.2.7?query=trolove - Wairau District (1853,16 July) Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, p. 3.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NENZC18530716.2.9?query=trolove

Websites

- Arrival of the "Wild Duck 11 December 1866

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ourstuff/ArrivalWildDuck1866.htm - The Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Nelson, Marlborough & Westland Provincial Districts] Marlborough Provincial District - The Marlborough Land District (published 1906)

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl.html - Heritage New Zealand. Woodbank Homestead.

http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/3692

Maps

Unpublished resources

- Levin, Nathaniel. (1864-1869) Inwards and Outwards correspondence. Alexander Turnbull Library

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22319656 - Trolove, Edwin, b 1832 : Diary, Alexander Turnbull Library

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22882213 - Trolove, Frederick William, 1831-1880: Commonplace book, Alexander Turnbull Library.

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22808622