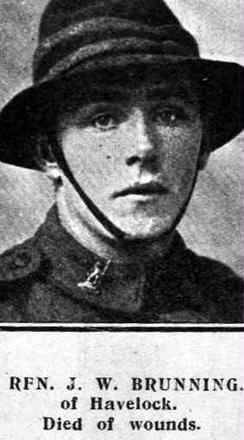

Rifleman John William Brunning

A Long Lost Brunning Tucked away at the bottom of a page in a Motueka community newspaper was a small item headlined "Long lost Brunning".

A Long Lost Brunning

Tucked away at the bottom of a page in a Motueka community newspaper was a small item headlined "Long lost Brunning". It featured the intriguing mystery of a Great War Certificate of Service with the NZ Expeditionary Force found in the shed of a Motueka resident, who had no idea how it ended up there, or who it should now belong to.1 Just visible was the name of Rifleman John Brunning, serial no. 5422, who commenced his duty on April 30th, 1917, and died in France in 1918. Who was this forgotten young man who never lived to claim his certificate?

John William Brunning was born at Canvastown, Marlborough, on the 4th of August, 1897, the first of ten children born to Richard and Betsy Brunning.2 However, his story really began on the other side of the world, 54 years earlier, when a young German couple from the province of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern made the momentous decision to emigrate to New Zealand in search of a better future.

Johann Matthias August Heinrich Brüning (1830-1901) a shoemaker by trade, and his wife Magdalena (Lena) Catharina Maria (née Lange) made the trek with their one year old son Friederich (Fritz) from their home in the village of Glashagen to the city of Hamburg. From there they sailed steerage to New Zealand on the ship Skiold, in company with around 130 other hopeful German emigrants, led by the Kelling brothers.3 They arrived in Nelson on the 1st of September, 1844, just in time for Lena, who barely made it to the NZ Company immigration barracks at Fort Arthur on Church Hill before giving birth to a second son, named Heinrich (Henry).4

They were greeted by the bad news that arrangements made in advance for the German settlers were in disarray, due to the financial collapse of the New Zealand Company. A number of the German emigrants chose to go on instead to South Australia, where prospects looked more promising,5 but Matthias and Lena stayed in Nelson. They squatted on an unclaimed section, where Matthias built a cob cottage. In 1846 they shifted to the tiny settlement of Schonbach in Waimea East, where Matthias built another cob cottage on a smallholding of 4 acres.6 Schonbach was close to the village of Ranzau (now Hope), established earlier by the Kellings for the Skiold immigrants, and named for their sponsor, Count Kuno zu Rantzau-Breitenburg. Under the terms of a prior agreement made with the New Zealand government, the German immigrants from the Skiold were all naturalised en masse as British citizens on April 3, 1845.7

In 1856 the Bruning family moved yet again after Matthias was granted sixty acres of Crown land (Sections 174 and part 173) at Upper Moutere, where a nucleus of German settlers was forming around Lutheran pastor, the Reverend Johann Heine, and his resourceful father-in-law Cordt Bensemann. A carpenter and former Hanoverian guardsman, Bensemann had arrived in Nelson with his family on the St Pauli in 1843. This new settlement was called Sarau after a northern German village of the same name.8 Like its counterpart Ranzau, it was renamed during the First World War and is today known as Upper Moutere.

By the time Matthias and Lena’s sixth son was born at Sarau, space must have been at a premium in the Brunings’ third and final small cob cottage. Baptised Dietrich Johann Christopher by Pastor Heine on 23 May, 1863, he was their ninth child. Dietrich’s closest siblings were Lena (3), Johann (John) (5), Anna (7) and Christopher (9). His older brothers Carl (Charlie) (12), Henry (19) and Friederich (20) would have been out working, and his sister Louisa (16) married Franz (Frank) Schwass when Dietrich was just five months old. The Schwasses later moved to Marlborough. A younger sister, Eleanora, was born three and a half years later.9

A school was built at Sarau in 1856, followed by the first St Paul’s Lutheran Church in 1865. Young Dietrich would have attended both. Like most boys, he probably finished school at the age of twelve or thirteen and started work around the district as a farm labourer, or at one of the Central Moutere flaxmills and sawmills.10 As families expanded, the children of the Sarau settlers had to look further afield for work, with many spreading out towards Motueka, Golden Bay and Marlborough, particularly as the Long Depression took hold in the 1880s and jobs became harder to find.

The majority of these children chose to anglicise their christian names so as to better fit into their predominantly British communities. Dietrich became known as both Richard and Dick, and may have deliberately changed his surname to the more English spelling "Brunning” which he and his descendants adopted. The Bruning family had long since abandoned the umlaut (ü) in their surname.

At some point Richard Brunning left Sarau behind and headed for Marlborough. Having a particular affinity with horses and an aptitude for handling horse-drawn coaches and waggons, he found work as a groom at a stables in Blenheim. His sister Louisa and her family lived nearby – her husband Frank Schwass was working as a bushman at Grovetown. By 1888 Richard and his 21-year-old nephew Larry Schwass were both at Onamalutu, an early settlement sited on the northern side of the Wairau River, fifteen miles north-east of Blenheim.11

Richard was working as a bushman and waggoner, handling waggons carting timber and the heavy horse teams used to drag logs from the bush. It’s likely that he was employed by sawmiller Charles White, who in 1901 donated a block of native bush for the Onamalutu Reserve, a small reminder of the days when the coastal Pelorus valleys were densely covered with lush, mixed broadleaf-podocarp forest. Horses were a source of pleasure as well as work, and Richard found time to make a good showing with his horse “Midnight” at the Marlborough Trotting Club races in 1894.12

In 1896 Richard, at age 33, was listed as a residential settler at Kaituna.13 Around this time he met 19-year-old Betsy Aroa, who became his common-law wife. Betsy assumed the surname Brunning, but although at one stage she gave a wedding date of May 27, 1897, it doesn’t seem that any such marriage actually took place.

Born in Kaituna, Marlborough, in 1878, Betsy Aroa was the last of ten children born to James Aroa (1830-1879) and his wife Ann (née Shaw), who married at Eston, North Yorkshire, in 1855. Betsy was only one year old when her father died at Picton Hospital during an operation to straighten a leg badly damaged in an accident some years earlier. Her parents had emigrated from Yorkshire, England, and when Ann Aroa came out in 1864 on the ship "Anne Dymes" with her four-year-old son Thomas, it's believed that she was joining her husband James, already in New Zealand by then. James was granted Crown leasehold land at Tua Marina. but finding the area too swampy, never settled there. He instead took up farming on a hundred acre block at Kaituna, and this is where he and his growing family lived. His family surname was originally “Airey”, but had always been spelt variably at a time when many were illiterate. It was recorded as "Harea" when he married. Once in New Zealand it became "Aroa".

Betsy had a connection with two well-known Marlborough pioneer families, the Popes and the Climos, through her sister Elizabeth Aby Aroa, who married James Climo, son of James and Jane Climo. His oldest sister, Elizabeth Catherine Climo, married George Pope, and in 1860 was the first person to discover gold at Wakamarina, gleaming in the gravel as she rinsed her washing in the river near the sawmill her husband and his brothers had set up there.15

Richard and Betsy moved to Canvastown, where their first child, a son, was born 4 August, 1897, and registered five days later on 9 August, 1897, under the name John William Brunning. As was the custom of the time, because his parents weren’t married, his status was recorded as “illegitimate”.16

Just a few miles down the Pelorus Valley from Havelock, Canvastown was originally a tent city, founded during the Wakamarina gold rush of 1864 on the spot where Elizabeth Pope first saw gold. Although the easy alluvial gold was soon exhausted, the settlement survived, and in the 1890s was an active service centre for a growing population of farmers, gold-miners working the nearby quartz reefs, and the extensive timber milling operations in the surrounding area, dominated by Brownlees & Co. Many of Brownlees’ workers settled in Canvastown so their children could attend the school there, and travelled daily to the felling areas by jiggers along the tramway systems set up to transport timber.17

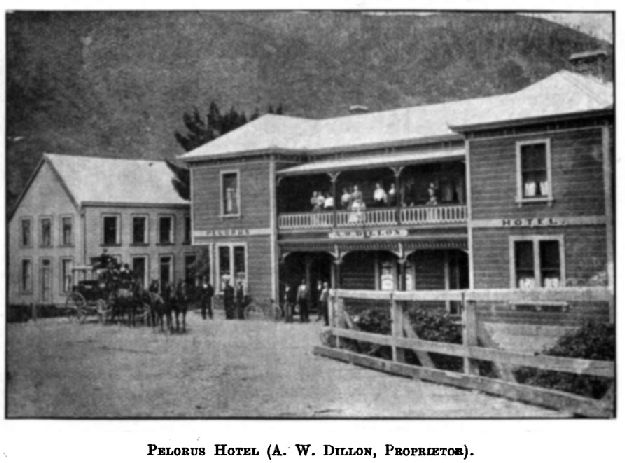

Richard took work driving waggons carting timber. A waggoner’s life was not an easy one, with each trip to Blenheim taking up to two days depending on the load and conditions. Halts were made at Havelock and Renwick, where up to a dozen waggon teams could be seen at any one time outside favoured hotels, the horses topping up from chaff bags while their drivers shared a meal and a beer or two. Several timber companies kept huts along the route where waggoners could stay overnight, though some chose to carry on by the flickering light of thick candles set inside carriage lamps. Each heavily loaded waggon was drawn by a team of six horses, and as many as eighteen waggons and over a hundred horses could be on the move at any one time, jostling for room along the deeply rutted Nelson-Blenheim road.18 When it rained the road turned into a quagmire, and loads of timber often shifted or were lost while crossing the Wairau River, which remained unbridged until 1913.

Young John William rapidly acquired seven brothers and sisters, born during the family’s years at Canvastown. They were: Herbert Christopher (Herb) (b.1899), Frederick Ernest (Fred), who later took the surname “Brown” (b. 1901), Leonard Nisbert (Len) (b.1903), Lindsay George (b. 1904), Margaret (Mona) (b. 1906), Noel (b. 1909) and Ella Magdalene (b. 1913).19 All four grandparents had died by the time he was four, but John had several Aroa aunts, uncles and cousins living nearby.

John was nearly seven when his father enrolled him at Canvastown School on 6 June, 1904, a small boy with reddish hair and blue eyes. He attended this school until he was fourteen, his last day there being 8 September, 1911. He was joined by his younger brothers; Frederick in 1906, Leonard in 1908 and Lindsey in 1909. His aunt Mary Jane Robinson (nee Aroa) also lived at Canvastown with her family and there would have been Robinson cousins at school with John and his brothers. Many children either walked long distances or rode horses to school.

Outside of school there were always chores to be done; gathering and splitting firewood, hand-milking cows, feeding poultry, plucking chickens for the pot and caring for horses. Entertainments were simple - playing marbles and blind-man's buff in the school playground, bird-nesting and gathering wild mushrooms and raspberries. Boys learnt to ride and shoot early, and as they grew older would go hunting for wild pigs, goats and deer in the remaining stands of bush. A fireworks display held at Havelock to celebrate the coronation of King George V on June 22, 1911, would have been a memorable occasion for local children.20

Richard Brunning continued to work with horses at Canvastown in various capacities, as groom, waggon-driver, teamster and stage-coach driver, until late in 1913. The family then moved to Rai Falls, not far from Canvastown, with Richard working as a stableman for the Newman Brothers, who ran a tri-weekly four-horse coach service carrying passengers and freight between Nelson and Blenheim from 1887, adding a mail service in 1891.21 From Blenheim there were five stages, with stables for changes of horses at Okaramio (next to Edward Hart's blacksmith’s shop); Canvastown; the Collins Valley “Half Way House”, and at Hira. The coach always stopped for lunch and a change of horses at the Rai Falls Accommodation House, mid-way point between Blenheim and Nelson.

At the Newmans’ changing stables at Hira, two separate teams were kept. The team used for the haul over the Saddle was composed of a strong heavier type of horse, while the team used to and from Nelson city was made up of light stylish horses picked as a show team. People in Nelson used to line Trafalgar Street to see the coach come in precisely at 6 o'clock. Drivers who couldn’t maintain the schedule didn’t last long in the job.22

John Brunning trained with the 12th (Nelson and Marlborough) Regiment of the NZ Territorial Forces and, before the war, was working as a labourer for a Havelock business styled E.O. Bensemann & Co., Blacksmiths, Wheelwrights and Coachbuilders. Edmund Oliver Bensemann was an Upper Moutere connection. His father, Johann Diedrich (Dick) Bensemann, was well known to Richard Brunning as one of the “five tall sons” of German pioneer Cordt Bensemann, first Sarau settler and owner of the Moutere Inn.

When he enlisted in Blenheim on the 13th of February, 1917, John Brunning gave his date of birth as 10 February, 1897, probably fudging so as to bring his age up to the minimum 20 years required for recruits. Although fit, at 5ft 4½in (164 cm) he wasn't a big lad and probably only just scraped through, with the minimum height requirement being 5ft 4in (162 cm). He would then have been sent to one of the military camps at Trentham or Featherston for training. He was one of ten men from Marlborough for the 27th Reinforcements who paraded in Market Place, Blenheim, on the 1st of May, 1917, and were farewelled by a large gathering, no doubt including John's family. Speeches were the order of the day, with speakers including the Mayor of Blenheim, John J. Corry, the Rev. Knowles Smith of the Wellington Methodist Mission, and Richard McCallum, M.P. A rousing rendition of the National Anthem (at that time "God Save the King") concluded proceedings and rather ironically, each departing man was issued with a book of tickets in the Marlborough Art Union lottery. The odds for this little group were better than most - of the ten who were fêted that day, eight survived the war to return home.23

The Marlborough men embarked on the troopship Athenic on 16 July, 1917, arriving 16 September 1917 at Liverpool, England. They were then deployed to the Western Front, with John Brunning being posted to A Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd NZ (Rifles) Brigade. He came down with a bad case of German measles and was admitted to hospital at St Omer. Once he was well enough he went back to the firing line and was wounded at Étaples on November 26, 1917. Upon recovery he continued fighting until July 1918, when combat stress perhaps caught up with him. He went briefly AWOL on 29th July, turning himself in to the Military Police the following day and forfeiting a day's pay in consequence. He rejoined his unit, which during August, 1918, was involved in fierce fighting to retake the German-occupied French villages of Pys and Miraumont during the Second Battle of Bapaume. John was seriously wounded on the 30th of August, 1918, and died later the same day while being treated by No 3 NZ Field Ambulance. He was buried at Grévillers, with Army chaplain, Rev. T.F. Connelly, conducting the committal service.24

By the time his parents received news of John’s death, the Brunning family had moved closer to the Blenheim area. Over the next few years they shifted several times, with Richard working as a farm labourer.25 Newmans’ horse-drawn coaches were a thing of the past, replaced in ever-increasing numbers throughout the war years by service cars. Although enthusiastically embraced by the younger generation, the transition to motorised transport was often difficult for those who grew up appreciating and working with horses.

The Blenheim Borough Council was moved to offer its sympathies to John Brunning's family during a meeting held on September 12, 1918: "A resolution of condolence was passed for communication to the relatives of Rifleman J.W. Brunning, who had recently made the supreme sacrifice." 26

Richard and Betsy's sixth son, Alan Cecil, was born the same year that John was killed. In April 1920, the Brunnings were living at Spring Creek when Alan, then two, contracted influenza and meningitis. Within a week he was dead. Still grieving for their oldest son, this second loss was a heavy blow for both parents, but appears to have been the tipping point for Richard. Over the following months he fell into a deep depression and turned to drink, becoming at times irrational and suicidal. He hanged himself in a cowshed at home on April 3, 1921, at the age of 59. An inquest held the following day concluded that "Richard Brunning committed suicide by hanging himself whilst temporarily insane due to excessive indulgence in liquor."27

It must have been a time of great hardship for Betsy, who was pregnant with their last child, Samuel Leio Steven Lionel (Steve), to whom she gave birth in Nelson on 5 September, 1921. She was staying with her sister Mary Jane Robinson, by then living in Beachville, and herself recently widowed.

The Brunning family drifted apart, with the older children leaving home to work and Betsy, with her youngest children, employed as a cook at various sheep-stations, including the 10,000 acre Mount Gladstone Sheep Station in the Awatere Valley. After 1946 she moved to the Motueka area. By then her sons Herbert and Len had married and were working at Ngatimoti in the Motueka Valley, and several of her Brunning in-laws were living around Motueka and Riwaka. Betsy worked for the Rose family at Ngatimoti for a time. The Roses were originally German settlers who farmed the area named after them – Rosental (Rosedale). Betsy was living at Ngatimoti when she died of heart failure on October 8, 1950. She was buried at Wakapuaka Cemetery in Nelson.28

The wartime period was a fraught one for those of German descent, who suddenly found themselves transformed from valued, hard-working neighbours into enemy aliens, despite having been British subjects from the earliest days of European settlement. They tried to keep a low profile, but often suffered abuse, bullying at school and discrimination. Nonetheless, many chose to fight for the British Empire, and including John Brunning, twelve of Matthias and Lena Bruning’s grandsons served during the First World War.

In Memoriam

BRUNNING. - in loving memory of Rifleman J.W. Brunning, killed in action on the 30th August 1918.

In a hero’s grave he sleepeth,

Somewhere in France he fell;

How little we thought when we parted

It was the last farewell

Inserted by his loving father and mother, sisters and brothers.29

2015

Updated May, 2020

Story by: Anne McFadgen

Sources

- A Long Lost Brunning (2015, 21 January) Guardian (Motueka, NZ), p.5

- Ancestry.com or Ancestry ProQuest (Library edition)

- Skiold, Hamburg, Germany – Nelson, New Zealand, 1844. Passenger List (Note: the Brunings’ young son Friederich was listed as Christian Bruning). NZ Family History website

https://www.geni.com/projects/New-Zealand-Settler-Ships-Skiold-1844/14634 - Bruning, M. (2014) To Seek my Fortune: Bruning family history: from Mecklenburg to Moutere. Tauranaga, NZ: Maureen & Norm Bruning. Ch. 2 Emigration Preparation, pp 15-22; Ch. 3 Arrival Upheaval, pg 51

- What Happened to the St Pauli Passengers? See Part 8 Potted histories of the Skiold passengers [A-Z Germans who remained or returned to New Zealand; A-Z Germans who settled in Australia or Overseas.] Lynly Lessels Yaytes Genealogy website:

http://www.lynly.gen.nz/index.htm#stpauli - Neuseeland: Nelson Settlements. Bensemann family website.

http://bensemann.org.nz/neuseeland.htm - Legislative Council of New Zealand. (1845) Session V, No II, 3 April, 1845. Ordinance for the Naturalization of certain German settlers in the Colony of New Zealand

- Sarau: Growing Sarau from the German Roots Up. Prow website

http://www.theprow.org.nz/yourstory/sarau - Bruning. Ch. 15. Richard (Dietrich) Pg 343

- McMurtry, George. (1992) A Versatile Community: The history of the settlers of Central Moutere. Upper Moutere, NZ: R.G.C. McMurtry. [See Index under Flaxmills and Sawmills.]

- Resident Magistrate’s Court: Dickson v Walton (888, June 22) Marlborough Express. [Richard Brunning, bushman and wagoner, and Lauritz (Larry) Schwass, labourer, of Onamalutu, both called as witnesses for the plaintiff.]

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX18880622.2.10 - Sporting News: Marlborough Trotting Club Races (1894, 6 March) Marlborough Express, pg 3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX18940306.2.27 - Richard Brunning: Electoral roll (Wairau) 1896

- Brayshaw, N.H. (1964) Canvas and gold: a history of the Wakamarina goldfields and lower Pelorus Valley. Blenheim, N.Z.: Brayshaw. Part One: Ch. 4, p. 10

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45550026 - Birth registration RGO 2869/1897 Pelorus

- Brayshaw. Part Two, Ch.4, Canvastown School, p. 183.

- Brayshaw.Part One. Ch. 23, Timber, pp. 141-2

- Ancestry.com or Ancestry ProQuest (Library edition)

- Bruning. Ch. 4, pp. 346-7

- Millar, J. H. (1965, rev. and enl. ed.) High noon for coaches. Wellington, N.Z: A. H. & A. W. Reed. Ch. 4 On the Blenheim Road, pp.57- 60; See also Ch. 13 A Groom Remembers, pp 75-80

- Newport, The Whangamoa-Rai Valley Road. In Wakapuaka, Nelson Historical Society Journal, 2(6), p.21

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ02_06-t1-body1-d2-d21.html - The Reinforcements: Marlborough Draft Farewelled (1917, 2 May) Marlborough Express, pg 5. Note: the article incorrectly mentions the 29th Reinforcements – it was in fact the 27th.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19170502.2.21.31 - Archives NZ, Military Personnel Record: John William Brunning

http://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE11152202 - Personal Notes: Death of Rifleman J.W. Brunning (1918, 10 Sept.) Marlborough Express, pg 5

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19180910.2.22.41 - Minutes of the Blenheim Borough Council, 12 September, 1918 (1918, 1 September) Marlborough Express, pg 4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19180913.2.18 - National Archives NZ J46 COR 1921/393. See also: Labourer's Suicide. (1921, 4 April) Ashburton Guardian. "Blenheim, This Day. Richard Brunning, aged 59, agricultural labourer, committed suicide at Spring Creek by hanging. He leaves a wife and seven children. He had been drinking".

- Bruning. Ch. 15, pp. 352-353.

- In Memoriam (1919, 30 August,) Marlborough Express, pg 4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19190830.2.21.4

Further Sources

Books

- Allan, R. (1965) Nelson: A History of Early Settlement. Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed.. See Ch. XI The German Settlements pp 309-352

http://www.worldcat.org/title/nelson-a-history-of-early-settlement/oclc/8650658 - Austin, Lt-Col. W.S., (1924) The Official History of the NZ Rifle Brigade. Wellington: L.T. Watkins. Online at NZETC See Ch. XV The Battle for Bapaume

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH1-NZRi.html - Brayshaw, N.H. (1964) Canvas and gold: a history of the Wakamarina goldfields and lower Pelorus Valley. Blenheim, N.Z.: Brayshaw.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45550026 - Briars, J. and Leith, J. (1993). The road to Sarau. Upper Moutere, New Zealand: Briars, J & J Leith.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39818669 - Bruning, M. (2014) To Seek my Fortune: Bruning family history: from Mecklenburg to Moutere. Tauranga, NZ: Maureen & Norm Bruning.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/890314185 - Leov, L.C.F. (1970) As the years went by, between Greville and the Rai. Spring Creek, Blenheim, New Zealand: L.C.F. Leov.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/152578569 - McMurtry, G. (1992) A Versatile Community: The history of the settlers of Central Moutere. Upper Moutere, NZ: R.G.C. McMurtry.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/versatile-community-the-history-of-the-settlers-of-central-moutere/oclc/240778426 - Millar, J. H. (1953) High noon for coaches. Wellington, N.Z: A. H. & A. W. Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/high-noonforcoaches/oclc/7830942 - Nolan, Tony (1976) Historic Gold Trails of Nelson and Marlborough. Wellington: A.H.& A.W. Reed.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/historic-gold-trails-of-nelson-and-marlborough/oclc/7248786

Newspapers

- Farnell, L. (2002) Beneath the Spreading Chestnut Tree [the Story of Blacksmith Edward Hart]. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 6(5), p.55

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ06_05-t1-body1-d7.html - Leov,L.C. (1974) Rai Valley Sawmills. Nelson Historical Society Journal,3(1), p.21

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ03_01-t1-body1-d8.html - Newman, J. (1957) Land Transport in the Early Days. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 1(2), pg.4

- http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH1-NZRi-t1-back-d6.html

- Newport, J.M.W. (1973) The Whangamoa-Rai Valley Road. In Wakapuaka, Nelson Historical Society Journal, 2(6), p.21

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ02_06-t1-body1-d2-d21.html - Wastney, Natalie (2009) A Post Office in the House. Nelson Historical Society Journal, 7(1), pg. 57

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ07_01-t1-g1-t10.html

Papers Past

- Bridge Commission: Minutes of a hearing regarding the need for a bridge over the Wairau River (1911, 4 April) Marlborough Express, pg 8

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19110404.2.37 - From Picton to Nelson by Coach: Comin’ Thro’ the Rai (1901, 1 June) New Zealand Illustrated Magazine, pg 693 (text only) [Account of a “girls’ trip” by Newmans’ coach from Blenheim to Nelson, written in an easy, breezy, rather flippant style by “K. Allen”, whose opinion of Nelson city incurred the wrath of the editor of Nelson newspaper, the Colonist. “One might expect the editor of the NZ Illustrated Magazine to keep clear of articles without any real merit to commend them, and offensive to a community,” he thundered (1901, 19 June) Colonist, Pg 2]

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC19010619.2.8 - Great Gale and Floods. Some Exciting Experiences. Serious Damage. Shipping Interfered With. A Coachdriver Drowned (1904, 21 March) NZ Herald, pg. 6

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NZH19040321.2.59 - In Memoriam: Rifleman J.W. Brunning (1919, 30 August) Marlborough Express, pg 4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19190830.2.21.4 - Labourer's Suicide. (1921, 4 April) Ashburton Guardian. "Blenheim, This Day. Richard Brunning, aged 59, agricultural labourer, committed suicide at Spring Creek by hanging. He leaves a wife and seven children. He had been drinking".

- Minutes of the Blenheim Borough Council, 12 September, 1918 Resolution to send condolences to the family of Rifleman J.W. Brunning (1918, 1 September) Marlborough Express, pg 4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19180913.2.18 - Nelson’s Mail Coach Services (Newmans’ advertorial). See Nelson – Blenheim Route. (1912, 24 February) Dominion, pg 15 [Coachman George Newman, a son of Newman Brothers’ founder, Harry Newman, was a regular driver on the Blenheim-Nelson ]

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=DOM19120224.2.117.5 - The Reinforcements: Marlborough Draft Farewelled (1917, 2 May) Marlborough Express, pg 5. [Note: the article incorrectly mentions the 29th Reinforcements – it was in fact the 27th.]

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19170502.2.21.31 - Resident Magistrate’s Court: Dickson v Walton (1888, June 22) Marlborough Express. [Richard Brunning, bushman and waggoner, and his nephew Larry Schwass, labourer, both of Onamalutu, called as witnesses for the plaintiff. Lauritz (Larry) Schwass was the son of Richard’s oldest sister, Louisa Schwass (nee Brunning) who married when Richard was a baby. Uncles and nephews of a similar age were common in the past, when mothers and their older daughters were often bearing children at the same time.]

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX18880622.2.10 - Sporting News: Marlborough Trotting Club Races (1894, 6 March) Marlborough Express, pg 3.

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX18940306.2.27 - The Timber Industry: The Marlborough Conditions (1901, 18 April) Marlborough Express, pg 4

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=MEX19010418.2.24 - The Upper Moutere Over Fifty Years Ago and Now: Opening of New German Church (1905, 29 May) Colonist, pg 5

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=TC19050529.2.24.7 - The Wakamarina Gold-Fields (1864, April 19) Colonist, pg 3

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=TC18640419.2.12

Websites

- Archway Archives NZ. Military Personnel Record: John William Brunning

http://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE11152202 - Auckland War Memorial Museum Database: John William Brunning.

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/C1844 - Brownlees & Co. Sawmilling Industry. Retrieved from Havelock Museum: Pelorus People, March 2015.

http://www.peloruspeople.org.nz/havelockmuseum/index.mvc?ArticleID=2 - Canvastown Memorial Hall. NZ History website, NZ Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/canvastown-memorial-hall - Cordt Heinrich Bensemann. Bensemann Family Website.

http://bensemann.org.nz/cordt.htm - Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Nelson, Marlborough and Westland Districts] (1906) Cyclopedia Company, Christchurch. Retrieved from NZETC [See: Marlborough Provincial District; The Sounds: for Blenheim, Canvastown, Havelock, Okaramio, Onamalutu, Rai Valley; Country Towns and Districts: for Spring Creek, Tua Marina.]:

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl.html - Easton, B. (2012) The Long Depression. Economic history - Boom and bust, 1870–1895', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 13-Jul-12.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-5 - Fatal Accident to the Nelson Mail Coach, 19 March, 1904. Timespanner blogspot.

http://timespanner.blogspot.co.nz/2009/06/fatal-accident-to-nelson-mail-coach-19.html - Fort Arthur, established on Church Hill, Nelson, as a safe haven for Nelson’s settlers, in response to fears of attack by Māori following the Wairau Affray in 1843. In Cowan, J. (1955) The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I: 1845–1864. Retrieved from NZETC.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/Cow01NewZ-fig-Cow01NewZ095a.html - Grant, D. Art Union Lotteries. 'Gambling - Lotteries and raffles', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 24-Apr-13.

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/gambling/page-4 - Havelock War Memorial. NZ History website, NZ Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/havelock-war-memorial - The History of the Upper Moutere Inn (PDF). Motuere Inn website

http://www.moutereinn.co.nz/uploads/8/5/7/8/85781138/the_history_of_the_moutere_inn_1012.pdf - James and Jane Climo. Family History NZ.

http://www.geocities.ws/familyhistorynz/jamesjaneclimo.htm - King George V, a biography. Who’s Who: King George V, First World War.com.[During a visit to the Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Flanders on 11 May, 1922, King George V gave an acclaimed speech which includes the famous quote: “In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon Earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.

http://www.firstworldwar.com/bio/georgev.htm - Lash, M (2013) The Kelling brothers, Carl (Charles) and Fedor. 'Kelling, Carl Friederich Christian and Kelling, Johann Friederich August', from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 29-Oct-2013.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/1k6/kelling-carl-friederich-christian - McKinnon, M. (2011) Marlborough places - Pelorus valley, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/marlborough-places/2 - Neuseeland, Nelson Settlements. Bensemann family website.

http://bensemann.org.nz/neuseeland.htm - New Zealand Company, Retrieved from Wikipedia, March 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand_Company - NZ War Graves Project. Rifleman J.W. Brunning, Adanc Military Cemetery, Miraumont, France.

http://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/casualties/john-william-brunning - Onamalutu Reserve. Retrieved from Marlborough Online, March 2015.

http://www.marlboroughonline.co.nz/index.mvc?ArticleID=9 - Richard McCallum. Retrieved from Wikipedia, March 2015.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_McCallum_(politician) - S.S. Athenic. Retrieved from Wikipedia March, 2015. Wikipedia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Athenic - St Pauli. Nelson Provincial Museum: Early Settlers Database.

http://www.museumnp.org.nz/early-settlers/voyageDetails.aspx?voyageid=42 - Skiold, Sailed Hamburg 21 April, 1844 – arrived Nelson 1 September, 1844. Passenger List.

http://www.museumnp.org.nz/early-settlers/voyageDetails.aspx?voyageid=58 - The Timber Industry of New Zealand (1905) Reports prepared by the direction of the Honorable the Minister if Lands, 1905. See Marlborough, pg 26. Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives, http://atojs.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/atojs?a=d&d=AJHR1905-I.2.1.4.10

- Tolerton, J. 'Coaches and long-distance buses - Service cars', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/coaches-and-long-distance-buses/page-3 - Tunnicliff, S. (2013) 'Newman, Henry and Newman, Thomas', from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 29-Aug-2013.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/2n10/newman-henry - Walrond, C. Johann Heine, Upper Moutere, 1880s. 'Nelson region - European settlement', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/28825/johann-heine-upper-moutere-1880s - The Western Front in 1918. New Zealand at War: First World War at the NZ History website. NZ Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/western-front-1918#heading2 - What happened to the St Pauli Passengers?. Lynly Lessels Yates’ genealogy website. [Extensive links to primary sources and further information about the German passengers from the ships St Pauli and Skiold.]

http://www.lynly.gen.nz/index.htm#stpauli