Nelson Lakes National Park

Nelson Lakes National Park (established in 1956) is situated in Te Tau Ihu - the top of the South Island, protecting 102,000 hectares of the northern most Southern Alps. The park offers tranquil beech forest, craggy mountains, clear streams and lakes both big and small.

Nelson Lakes National Park (established in 1956) is situated in Te Tau Ihu - the top of the South Island, protecting 102,000 hectares of the northern most Southern Alps. The park offers tranquil beech forest, craggy mountains, clear streams and lakes both big and small. The gateway to the park is St Arnaud.

The name "Nelson Lakes" was formally adopted by the National Parks Authority at a meeting in 1956 following proposals for various names from the public. Nelson Lakes was the most favoured.1 There are a number of Lakes in the Park, but the largest, and the ones which were first protected are Lakes Rotoiti (small waters) and Rotoroa (large waters).

Significance to Māori2

The area now covered by Nelson Lakes National Park, is a region of significance for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Ngāti Kuia, Rangitāne o Wairau, Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Tama ki Te Tau Ihu, Ngāti Toa Rangatira and Te Atiawa o Te Waka-a-Māui, and before them Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri. Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Waewae hapu also have a connection with Lake Rotoroa and the area to Murchison.

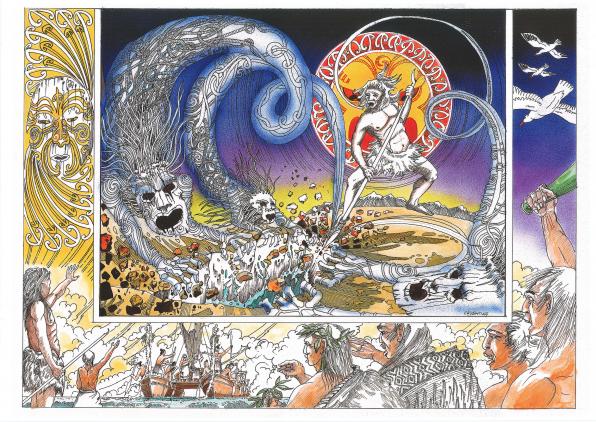

According to Ngāti Apa and Rangitāne the Lakes are the eye-sockets of the great wheke (octopus) Muturangi, which Kupe fought in the Tory Channel to save his fishing grounds.

According to Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Tama, the origins of Lakes Rotoiti and Rotoroa are linked to the tradition of Rākaihautū, of the Uruao waka, which arrived in the South Island from Hawaiki around AD 850. Landing near Nelson this Māori chief found his way overland through the heart of the South Island. Near the Buller he dug three large trenches in the ground with his Ko (digging stick). The holes filled with water and became Lakes Rotoroa, Rotoiti and Rangatahi (now known as Lake Tennyson).

For each iwi the Lakes are an important source of the rivers running through their rohe, and the hub of significant tracks linking their whanau and communities in Te Tau Ihu, and, for Te Ati Awa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Tama, to the West Coast Pounamu trails. The land and lakes provided plentiful mahinga kai and a shrub called neinei, which is highly prized for its use in korowai. Up to the time of European settlement the Lakes were also a site of cultivated fern gardens, the burnt off slope by Lake Rotoroa was probably a fern garden, with waka landing sites and evidence of temporary and some permanent shelter huts. Middens have been located at Kerr Bay, Travers Valley and Matakitaki. For Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Kuia and Rangitāne the Lakes provided a refuge from the invasions of Te Rauparaha and the northern tribes. At that time, much local knowledge, particularly that of Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri, was lost.

Ngāti Apa have strong associations with the tarns and smaller lakes within the area. Rotomairewhenua / Blue Lake or ‘the lake of peaceful lands’ was traditionally where hauhanga (bone cleansing) ceremonies were carried out for the bones of deceased males. Rotopōhueroa / Lake Constance or ‘the long calabash’ was traditionally used for the hauhunga ceremonies involving deceased females. The cleansed bones were later deposited in Te Kai ki o Maruia (the Sabine Valley). The four small tarns of Paratītahi and the larger tarn Paraumu (both meaning purpose in life) were important in ceremonial initiation ceremonies for young Māori. Rotomaninitua / Lake Angelus, the maunga Maniniaro / Angelus Peak and Rotomaninitua / Lake Angelus are markers and resting places on the pathway of deceased Ngāti Apa as they make their journey to the West Coast and Te One Tahua/ Te Reinga (Farewell Spit) and ultimately Hawaiki.3

European exploration and settlement4

The poor and rugged land of the Nelson Lakes area was not immediately appealing to Settlers. However, as the lack of suitable land for farming in Nelson became apparent, they began exploring South, and travelled into the Nelson Lakes - but were disappointed with what they found. In 1843 Cotterell “discovered” Lake Rotoiti and explored the Travers Valley.5 Brunner later followed the Buller from its source in Lake Rotoiti. Towards the end of 1843 (after the Wairau Affray), Charles Heaphy and John Spooner explored to the South West as New Zealand Company agents. Heaphy reached Rotoiti and started place-naming: the Buller was named Fox River, Rotoiti Lake Arthur, Rotoroa Lake Howick (after Lord Howick) and a nearby peak Mt. Cotterell. They made it to the Gowan and turned for home. In 1846 Fox, Heaphy, Brunner and Kehu explored from Rotoiti to Rotoroa along the Howard Valley over to Matakitaki, via the Porika track, and back along the Buller.

Julius von Haast, a geologist searching for minerals around Rotoiti in 1860, explored and named Mt. Robert, Mt. Christie and Lake Rotoroa. He also gave the first reports of the natural history of the area - including sightings of Kokako, kakapo and kiwi as well as descriptions of the geology.

Gold and growth

In 1862 gold was found near Mount Rochfort along the Buller River. George Fairweather Moonlight later fossicked around Glenroy and discovered more gold, after which the N.W. fringes of what was to become the National Park was caught up in a gold frenzy. A track was built and a ferry took passengers across the Gowan at Lake Rotoroa so they could travel to the West Coast.

In 1864 the Matakitaki overtook Lyell as the main gold working area. The 14 room Mammoth Hotel was established by a flamboyant character called “King Tom May,” who may have been murdered for his gold as he suddenly disappeared. Many Chinese also joined the miners. More accommodation, pubs and stores were set up in Matakitaki and a settlement of Howard6 was pegged out but never built as the promise of more gold waned throughout the region. The Matakitaki saw several revivals in gold working. mainly with Chinese, and as late as 1916 a company was set up in the Howard River. During the depression unemployed men were set to working the area, but all with very little return. The Mammoth Hotel closed its doors in 1951. In the 1860s the villages of St Arnaud and Murchison grew and survived by supplying meat and wool to the gold diggers.

George McRae was the first settler in the district in the 1840s, settling in what became known as Lake Station. Others followed in the Braeburn, Matakitaki, Howard and Mole Valleys. in 1862 Lake Station was taken over by John Kerr, developing it into a substantial run.7 He released brown trout8 into the lake, bred racehorces and lobbied for the building of roads and bridges - access remained challenging until the present highway was built in the last 1920s. Soon the land, in what was to become the park, was overrun by wild cattle and sheep, as well as introduced wild game animals (rabbits, hares, deer, pigs) causing significant land degradation and erosion - the face of Mount Robert was "accidentally" burnt in 1887 and is still recovering today. Deer were protected until as late as 1924.

Recreation and Protecting the land

James Hector and Haast had predicted that one day there would be a reserve around the Lakes, but most settlers hated the rugged land. The Nelson Acclimatisation Society,9 established in 1863 actively introduced ungulates and fish, which impacted heavily on bird and plant life and brought hunters to the area. In 1881 Bishop Suter took a party to Rotoiti and held a service. In the early 1900s a small reserve was created around the Lake. In the 1920s F.G. Gibbs led a group of enthusiasts to secure the land round Lake Rotoiti for the public, as it was being threatened by increased development. The Rotoiti Scenic Reserve was created, managed by the Rotoiti Domain Board with F.G. Gibbs as Chair for many years.

In the 1930s the advent of the car brought more visitors, which increased recreation in the area and a desire to protect the land - skiing, tramping, boating10, walking were all popular. St Arnaud grew. In 1956 the Nelson Lakes National Park11 was established. In the 1960s the momentum for preservation of the landscape and its wildlife grew. In 1967 Matakitaki Lodge and in 1968 the educational centre of Rotoiti Lodge12 were built. In 1980 the National Parks Act was passed and under it, in 1983 Matakitaki and the Glenroy Valleys were added to the Park.

The Rotoiti Nature Recovery Project was established in 1997, as one of six Department of Conservation ‘mainland islands’, with a focus on conducting research into pest management methods and sharing the lessons learnt. The site at Rotoiti was selected because it contained montane honeydew Nothofagus beech forest typical of the indigenous cover of the northern South Island of New Zealand. The initial area of 825 hectares is close to the park’s visitor centre at St Arnaud and easily accessible for staff and for the public. Since its establishment major pest control efforts have resulted in a significant improvement in native bird numbers and forest health. Mistletoe is becoming more visible, small groups of kaka can be spotted and great spotted kiwi have been reintroduced and are breeding successfully.13

Huts

There are 25 huts and shelters in the Park, mainly along the popular tramping routes. The first DOC Hut was Coldwater Hut, built in 1963. Lakehead Hut14 followed in 1978, with a major upgrade in 1996. The most popular hut is Angelus Hut, opened in 1956 as a four-man hut by the Nelson Ski Club in 1956, it was replaced in 1970 by the Department of Conservation as a 16 bunk hut. A new 28 bunk hut was opened in 2010. John Tait Hut15 on the Sabine Travers route is another of the bigger huts - the original hut was built in 1951 by John Tait, then President of the Nelson Tramping Society.

The Porika or Parika is an old Māori track from the west coast (pounamu area) to the Lakes Rotoroa and Rotoiti (sources of mahinga kai) and further east and north. It is thought that the name16 was probably a corruption of the Māori name for parrot (kakariki). Kehu showed route to the early explorers Fox, Heaphy and Brunner in 1846, when they were seeking more land suitable for pasturage, and subsequently as a route to the west coast. Early prospectors started using the track when looking for gold (Moonlight was one of the early prospectors, from the 1860s). When gold was found in the Howard Valley in 1874 traffic increased from the West Coast across the Porika to the new goldfields and Lake Station (established in the west side of Lake Rotoiti by John Kerr in the 1860s).17

Kerr set up the Do Drop Inn on the Porika in the 1860s to feed and water travellers. In 1866 a bridge was built across the Gowan River at Lake Rotoroa establishing an all weather route from that direction up the Porika. The track fell out of use as the roads were improved from Nelson to the Buller across the Hope Saddle and it was never sealed; it was still used, however, for foot and horse traffic as gold prospecting in the Howard continued into the 1930s. The 1938 application to make the track into a vehicular route was not successful. It is now a 4x4, bike and walking track, with old gold diggings along it, across some DOC and private land and the ridge along which it runs has given its name to New Zealand's Porika glaciation period.

2021

Story by: Nicola Harwood

Sources

- New Zealand Gazetteer on Land Information New Zealand:

https://gazetteer.linz.govt.nz/ - Te Tau Ihu Statutory Acknowledgements 2014, Nelson City Council, Tasman District Council, Marlborough District Council:

http://nelson.govt.nz/assets/Environment/Downloads/TeTauIhu-StatutoryAcknowledgements.pdf - Te Tau Ihu Statutory Acknowledgements 2014, p. 17

- Potton, C. (1985; 1988) The story of Nelson Lakes National Park

Nelson [N.Z.] : Dept. of Conservation ; Auckland, N.Z. : Cobb-Horwood Publications, distributors

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/154172055 - Cummings, D. (1992) Travers Valley and Reminiscences, 1842-1990. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p. 21

- Jenkins, P. (1992) Dora Perry's memories of the Howard goldfields. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p. 93

- Butters, W. (1992) The Kerr family of Lake Station. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p. 7

- Butters, W. (1992). Brown trout and other acclimatised fish of Rotoiti and Nelson Lakes National Park. In. Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p.36

- Sowman, W. (1981) Meadow, mountain, forest and stream the provincial history of the Nelson Acclimatisation Society 1863-1968. Nelson: Nelson Acclimatisation Society

- Shuttleworth, R. (1992) Boating at Lake Rotoiti 1880-1990. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p.40

- Lyon, G. (1992) Twenty-one years as Park ranger. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p.137

- Lyon, G. (1992) The advent of Rotoiti Lodge. In In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p.151

- St Arnaud forest gets a second chance (1997, January 29), Nelson Mail, p.17

- Lakehead Hut Lake Rotoiti (1996, August 26) Nelson Mail, p.10

- Norris, J. (1992) Recollections on the building of the John Tait Hut. In Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.), p. 49

- Brown, M. (1885) Difficult country: an informal history of Murchison. [Murchison, N.Z.] : Murchison Historical and Museum Society

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/oclc/154272259 - Newport, J. (1962) Footprints : the story of the settlement and development of the Nelson back country districts. Christchurch [N.Z.] : Whitcombe & Tombs, https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/oclc/18091608; Newport, J. (1987) More footprints. Nelson, N.Z. : J.N.W. Newport. https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/oclc/37444985

Further Sources

Books

- Dungan, E. (ed) Rotoiti Recollections. St. Arnaud Community Association (Tasman District, N.Z.)

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/154645532 - Horst, E. (1967) Nelson Lakes National Park : a handbook for visitors. Nelson, Nelson Lakes National Park Board [1967]

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/154198821 - Nelson Lakes National Park. Resource Manual (1981) New Zealand: Dept of Lands and Survey

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/8765804 - Our park, our place = No tatou te whenua, ko tatou te rohe : Nelson Lakes National Park 50th anniversary commemorative booklet. (2008) [St. Arnaud, N.Z.] : Dept. of Conservation, [2008]

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/225852995 - Potton, C. (1985; 1988) The story of Nelson Lakes National Park. Nelson [N.Z.] : Dept. of Conservation ; Auckland, N.Z. : Cobb-Horwood Publications, distributors

https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/154172055

Newspapers

- Haley, A. (1993) Lake Rotoiti Holidays. Journal of the Nelson and Marlborough Historical Societies, 2(5), p.3

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ05_05-t1-body1-d1.html - John N. Blechynden of the Roundell (1995) Journal of the Nelson and Marlborough Historical Societies, 2(6), p.37

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ05_06-t1-body1-d10.html

Websites

- Steffens, K. (2009) A history of threatened fauna in Nelson Lakes area. Dept of Conservation, Nelson/Marlborough Conservancy [PDF]:

https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE1360346 - National Lakes National Park. Retrieved from DOC:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/nelson-lakes-national-park/?tab-id=50578 - Rotoiti Nature Recovery Project 1997. Retrieved from DOC:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/nelson-lakes-national-park/rotoiti-nature-recovery-project/