Ngawhatu Hospital, Orphanage and Valley

The Orphanage Era of Ngawhatu Valley Orphanage stream in in Stoke takes its name from a Roman Catholic home for boys which was once sited in the Ngawhatu Valley. Commonly called the Stoke Orphanage, the home had an official name of St Mary’s Industrial School.

The Orphanage Era of Ngawhatu Valley

Orphanage stream in in Stoke takes its name from a Roman Catholic home for boys which was once sited in the Ngawhatu Valley.

Commonly called the Stoke Orphanage, the home had an official name of St Mary’s Industrial School. This name arose from the Industrial Schools Act of 1882 under which St Mary’s Orphanage, sited in Manuka Street Nelson, was gazetted. The Stoke branch of the orphanage opened in August 1886 in a purpose-built, 150-bed complex, and was officially for boys eight years and over who came from all over New Zealand. In addition to schooling they were offered training in farm work, gardening and trades.

When the orphanage opened, Nelson and New Zealand was in the grip of an economic depression. Many of the children accepted by the institution were homeless and living in the streets. Others did have homes, but their parents were unable to feed or care for them. Food, health and survival were on people’s minds. The Stoke orphanage, positioned on a hill, was regarded as ‘...ideal, being dry and healthy; a place where the most delicate boy would have the very best chance of developing into sturdy manhood.’

In 1889 the Catholic Church was experiencing management problems with the orphanage and they asked the Marist Order, a French lay-teaching order, to take charge. The brothers had high hopes but they were not trained in the full time care of youngsters. To add to their difficulties, the orphanage quickly became overcrowded.

During its 33 years of operation, the school’s management was not without controversy, particularly relating to inmates' hunger and punishment. With the addition of a new dormitory wing in 1894 the orphanage reached its peak attendance of 250 boys. Nine years later the landmark building burned down. A new complex, built with bricks made on the premises, was opened with ceremonial fanfare in 1905. Following the sale of the orphanage to the government five years later, the name was changed to the Boy’s Training School, also known as the Stoke Training Farm. Changes in government policy led to its closure in 1919.

Few images of orphanage life were ever published and those that appeared in local newspapers were carefully orchestrated. Recorded memories repeatedly speak of a darker side – hunger, hard work and severe discipline. Those who thrived developed enterprising strategies. Birds' eggs were collected from nests and consumed; the fowlhouse raided and eggs wrapped in mud and cooked over an open fire; eels caught in the stream; carrots and turnips eaten raw from the fields and loaves sneaked from the bread cart as it went up the hill. During kitchen chores butter and sugar were taken to make toffee. Survivors certainly learnt how to look after themselves. These skills may have helped some of the 69 inmates (past and present) from the ‘Stoke Training Farm’ who volunteered to serve their country, to survive the horrors of World War 1.

The Commission of Enquiry

In 1900 James Maher and Albert James ran away from the Stoke Orphanage. Their truancy resulted in a series of events that brought about much needed improvements in care.

When one of the runaway boys wrote to a friend back at the orphanage, their whereabouts was discovered. They were arrested and returned into custody to be punished. Rumours of excessive punishment at the orphanage had been circulating in Nelson for some time and the incident prompted members of the Charitable Aid Board to pay a surprise visit. What they found, including solitary confinement cells that were used for up to three months, and whipping on the hands with supplejack vines, resulted in a Commission of Enquiry.

The Enquiry brought about changes, including the departure of the Marist Brothers. A matron was now permitted to be employed at the orphanage while management, schooling and discipline practices became aligned with other Industrial Schools. The Enquiry and subsequent dropping of assault charges against some of the brothers was controversial. The Commission felt much of the evidence by the boys was tainted with exaggeration. Newspapers stirred emotions by likening the school to Dickens’ Dotheboys Hall and lamenting the sad conditions of this ‘charitable’ institution.

A new building

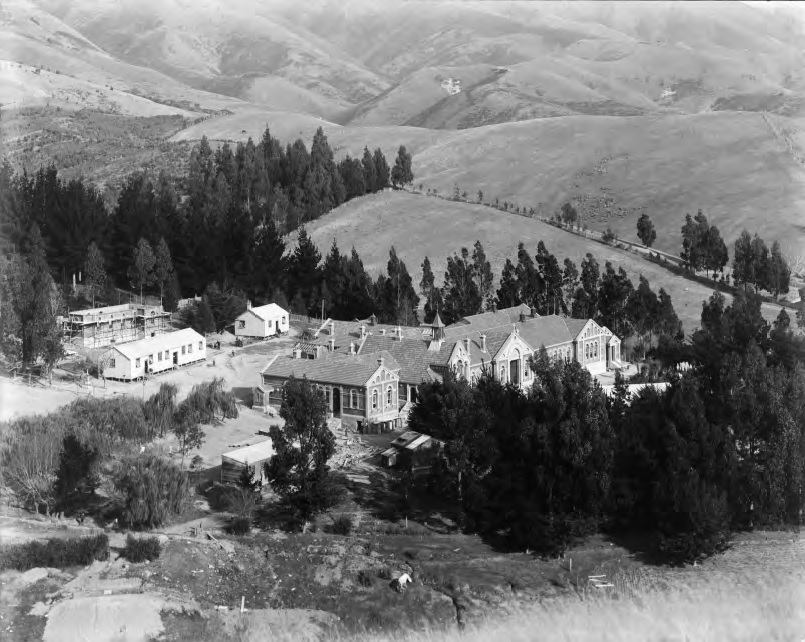

In 1905 a new orphanage building was opened, as the institution prepared for transition to a hospital. In the photograph to the right, the new 1905 building can be seen, alongside temporary buildings and the detached hospital under construction.

The large brick building accommodated 100 boys in two dormitories and contained a chapel with bell tower, large dining room, classrooms and also workshops to teach sewing, knitting, bootmaking and carpentry. Construction used 300,000 bricks made on the property, with a red-coloured roof of imported Marseilles tiles. When this building was finally demolished in 1967, following a long period of use as the ‘Main Building’ of Ngawhatu Hospital, the tiles were of such value that they were carefully removed, one by one, and sent down a cloth chute to be stacked on the ground ready for resale.

St Marys Orphanage Cemetery

Twenty four boys who died at the orphanage were buried in a nearby cemetery . The first burial was Arthur Blane, age 7 years, who died of meningitis in 1886. The youngest orphan to be buried was 6 years old. Another burial was of John Roger. At age 13 he was threatened by other boys with a dunking in the newly formed bathing hole in Orphanage Stream, and ran away. Despite extensive searches, his body was not discovered for four months. Priests carried out most of the burial services that took place here, with the boys carrying the casket up the hill. A new headstone listing all burials was placed at the cemetery in 1998 and includes the names of two adults including John Brosnahan, a former orphanage boy who sadly drowned while on a visit in 1919.

The Hospital Era

Following the early Stoke Orphanage era, the Ngawhatu Valley became home to hundreds of mental health patients for almost 80 years. Mentally ill patients were first cared for in the Nelson Lunatic Asylum, on the "Braemar campus" site between Franklyn and Motueka Streets on Waimea Road. This opened in 1876. It was renamed the Nelson Mental Hospital in 1912 and then the Braemar Hospital and Training School in the 1960s. The majority of adult patients with mental illness were relocated to the Nelson Mental Health Hospital in Ngawhatu in 1922. Children and those with intellectual disabilities remained at Braemar.1

The Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital used the large brick Stoke Orphanage building as its first ‘Main Building’. Over the years the hospital spread into the tranquil hills behind Stoke with an infrastructure of residential villas, administration and support service buildings, sports facilities, gardens, orchards and farm buildings.

In 1949 Rina Moore, reputedly the first Māori woman to graduate as a clinically qualified Doctor (MB, ChB) started working at Ngawhatu Pyschiatric Hospital. She was a pioneer in building links between the community and the institution, helping to break down public fears and prejudices about mental illness, and became increasingly active on controversial issues, including being one of the first doctors in New Zealand to prescribe the contraceptive pill in the early 1960s. She worked at Ngawhatu for 15 years, for some time in charge of the women's unit, but passed over for promotion, she resigned in 1963.

Over the years buildings were demolished, while others were built, moved or upgraded to provide up-to-date services. By the late 1980s a process for the closure of the institution began reflecting changing values of how mental health patients should be cared for. ‘Ngawhatu’, as it was locally called, touched many Nelsonian’s lives – short-stay patients, resident patients, medical and nursing staff, domestic and casual staff, gardeners, patients’ families and friends. Like the Stoke Orphanage, it was an institution of its time.

The Villa System

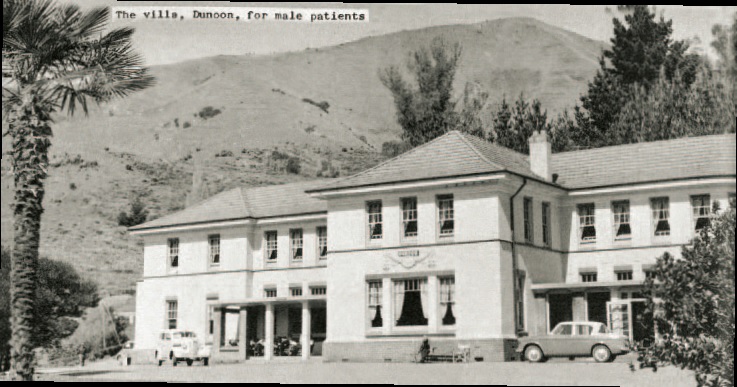

The housing of patients was by a villa system that evolved over several decades. This was ‘the most modern method known to science’ of psychiatric care in the early 20th century and Ngawhatu led the way.

The first villa to be built was Viewmont. At this stage only male patients were received, but following the completion of another three villas in Highland Valley, women moved out to Ngawhatu from Nelson Hospital. When villas in York Valley were completed between 1935–1939, York became the female valley while Highland was for the men. This segregation continued until the mid 1980s at which time villas became integrated. At its peak the hospital had 13 villas, each housing around 40 to 60 people.

Community in the Valley

For many patients, Ngawhatu was their home. The park-like surroundings and provision of facilities enabled many patients to wander freely in the gardens and play games such as croquet, tennis and bowls. Many patients worked on the farm, in the laundry or helped within the villas. The farm had dairy herds, pigs, sheep and poultry. A testament to the quality of farm work by patients and staff was reflected in the many A&P Show award ribbons won annually in various categories. Other patient/staff successes were the construction of a bowling green in front of Kinross Villa in 1942 and the building of a sports pavilion in 1968 by 30 patients. Many patients enjoyed activities such as basketball, baseball, cycling, athletics, theatre, growing vegetables and tending flower gardens.

A New Era

It was in the 1950s that attitudes towards psychiatric care began to change, culminating in the belief that institutions denied people basic human rights and that community living would create better social and health outcomes for residents. From the 1980s onwards, former staff residences on the hospital property were utilised to prepare patients for independent living. Highland House and Grove Cottage became rehabilitation units.

Although Ngawhatu was no great distance from the expanding Nelson and Richmond urban communities, it was a community in itself. The winding valley roads and buildings hidden behind foothills created a secluded and visually detached environment that no longer aligned with modern medical practice. By the late 20th Century the once state-of-the-art villas were well past their use-by date.

All patients were relocated into the community by the year 2000 and the Ngawhatu land sold in 2001. Today, trees that were once planted and cared for by gardeners and patients are some of the most visual reminders of the Hospital era. Many have been given heritage status, along with some from the Orphanage era. The once sprawling Ngawhatu Hospital buildings are almost all gone, but the place will remain for many more decades in the memories of those whose lives it touched.

The naming of Ngawhatu

One story behind the name Ngawhatu comes from the great Mäori navigator Kupe. When winning a battle with the giant octopus Te Weke, Kupe delivered a fatal blow that sent the creature’s eyeballs flying. One landed in Cook Strait to form Ngä Whatu Kaipono / The Brothers Rocks, while the other was thrown all the way to a valley behind Stoke. The full name of the valley is Ngä Whatu o Te Wheke o Muturangi (The Eyes of The Octopus Of Muturangi). Another legend speaks of Ngawhatu Valley being formed by the body of Te Wheke as it was split in two.

A professional perspective

“Over the course of my career it's been fascinating to think about how the treatment of mental illness has changed. The 'moral management' of the early 20th century asylums emphasised work, exercise, recreation and church services to care for troubled souls. There was little else to offer and many lived out their lives at Ngawhatu. Staff were instructed to care humanely for the residents but a cure was not usually expected. From the 1930s psychiatrists and nurses provided medical treatment with the few options they had. Through the 1950s and again in the 1990s, medications became increasingly refined and better targeted.

In time and with new attitudes, the long-term residents at Ngawhatu were able to live in community homes and elderly people with dementia were no longer sent 'up the valley' but could now live in purpose-built rest homes. Acute patients had shorter stays and more support to recover and return to their lives.

I was among the first few psychologists who came to Nelson to use our knowledge to understand and relieve distress and work with patients to develop their well being. Psychology is now a growing field and there's widespread interest in how our minds work and how to make the best of ourselves.”

Jan Marsh Clinical Psychologist at Ngawhatu 1975-77 and 1991-1994

More on St Marys Orphanage in Nelson and Stoke [PDF] or contact St Mary's Parish archive

This information was produced for a Nelson City Council Heritage Panel located at Orphanage Stream in Stoke, 2016. Updated 2021

Story by: Janet Bathgate and Nelson City Council

Sources

- Beatson, B. (accessed 18 November 2021) Moore, Rina Winifred, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 2000. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5m56/moore-rina-winifred

Further Sources

Books

- Crawford, P. (1995) Only an orphan : first-hand accounts of life in children's institutions in New Zealand. Lower Hutt [N.Z.] : MJC Pub

http://www.worldcat.org/title/only-an-orphan-first-hand-accounts-of-life-in-childrens-institutions-in-new-zealand/oclc/37742077 - Harris, A, (1994) The beauty of your house. Nelson, N.Z.: St Marys Parish

http://www.worldcat.org/title/beauty-of-your-house-the-nelson-catholic-parish-1844-1994/oclc/39968304 - Hunt, C. (1981) Speaking a silence. Wellington, N.Z.: Reed, p.14-31

http://www.worldcat.org/title/speaking-a-silence/oclc/9576171 - Low, D.C. (1973). Salute to the scalpel. A medical history of the Nelson Province, etc. Nelson, N.Z.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/salute-to-the-scalpel-a-medical-history-of-the-nelson-province-etc/oclc/560833290 - O'Connor, M.E. (2008) Salisbury School : a lesson in special education. Nelson, N.Z.: Te Whanau o Salisbury

http://www.worldcat.org/title/salisbury-school-a-lesson-in-special-education/oclc/313744700 - Stoke Industrial School, Nelson (report of Royal Commission on, together with correspondence, evidence, and appendix) Govt Print 1900. [held Nelson Public Library or, in NZ. Appendices to the Jnls of the House of Representatives]

- Webby, Majorie M. (1991). From prison to paradise - genealogy of Ngawhatu Hospital previously known as Nelson Lunatic asylum 1840-1991 and St Mary's Orphanage of Stoke. Nelson: The Author.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/from-prison-to-paradise-genealogy-of-ngawhatu-hospital-previously-known-as-nelson-lunatic-asylum-1840-1991-and-st-marys-orphanage-at-stoke/oclc/156415681

Newspapers

- Ansley, Bruce (1993, 4 Dec). In the brothers' keeping. Listener, 1993; 141 (2800), 24-26

- Arnold, Naomi (2014, 24 May) Hard times and healing. Nelson Mail, p15

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/features/weekend/10080478/Hard-times-and-healing - Collett, Geoff (2000, July 1) Ngawhatu bids farewell The Nelson Mail

- Long, J. (2016, November 14) Inferno destroys 87-year-old Nelson building at Ngawhatu. Nelson Mail on Stuff:

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/news/86422462/inferno-destroys-87yearold-nelson-villa - Manning, David (1985, November 9) Ngawhatu-an open door to mental care.Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu – Modern Home of Healing In Peaceful Valleys (1967, October 14) The Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu: 637 Patients and 150 Nursing Staff (1971, July 2) Nelson Evening Mail

- Ngawhatu part of damning report (2007, June 29) Nelson Mail, The p. 1.

- Roll call at orphanage. Dominion Post. 21/04/1999, p2

- Shaw-Miller, N. (2013) History and memories of Braemar Hospital. Nelson Historical Journal, 7(5), p.48

- Smith, Dawn (1993). The boys in the valley. Journal of the Nelson and Marlborough Historical Societies, 2,(5) 21-26

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-NHSJ05_05-t1-body1-d4.html - Wetere, Mere. (1997, 22 Mar). Grave raid stirs stones of orphans' neglect Evening Post, p.14

Websites

- Catholic Industrial schools (1907, 3 October). New Zealand Tablet, XXXV (40), p. 35

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZT19071003.2.56 - The Cyclopedia of New Zealand : industrial, descriptive, historical, biographical facts, figures, illustrations. V.5 Nelson, Marlborough and Westland provincial districts.(1897-1908) Wellington, N.Z.: Cyclopedia Co, p.61

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc05Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d1-d12.html - Ngawhatu from the air (1970, October 17) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN120_19701017/t1-body-d20.html#NPN120_19701017_025a - Ngawhatu (1961, October 14) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN12_19611014/t1-body-d10.html - Ngawhatu: a leader in the field (1971, June 26) Nelson Photo News

http://photonews.org.nz/nelson/issue/NPN128_19710626/t1-body-d20.html - St Mary's Industrial school, Stoke. (1900, 1 August) Colonist, XLIII, (9856), p. 2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC19000801.2.9 - St Mary's Industrial school, Stoke: solemn opening new building at Stoke (1905, 29 May) Colonist, XLVII, (11344), p. 6

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC19050529.2.24.13 - St Mary's Orphanage, Stoke. (1908, 13 August) New Zealand Tablet , p. 13

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZT19080813.2.15.2

Maps

- Ngawhatu Psychiatric Hospital 1922-2000. Archway Agency:

http://archway.archives.govt.nz/ViewEntity.do?code=AEJU - St Mary’s Boys and Girls Orphanage Registers & Sunnybank Boys Home Registers. Some Registers as early as 1850. Held St Mary’s Parish Archives/Museum, 18 Manuka Street, Nelson. Phone NZ 03 5489527 (or contact the Archivist, St Mary's Parish, P.O.Box 37, Nelson)