The Golden Waikoropupū

Legends of taniwha protecting the healing waters of the Southern Hemisphere’s largest cold water springs, tales of hardship in the backbreaking search for gold, and the story of how the prospectors’ leftovers are used to generate power.

Legends of taniwha protecting the healing waters of the Southern Hemisphere’s largest cold water springs, tales of hardship in the backbreaking search for gold, and the story of how the prospectors’ leftovers are used to generate power. All can be found in the Waikoropupū Valley in Golden Bay / Mohua.

Māori regard Waikoropupū Springs, near Tākaka, Mohua/Golden Bay, as taonga and wāhi tapu. Ngāti Tama Ki Te Tau Ihu and Te Ātiawa O Te Waka-A-Māui record that Huriawa, the taniwha of Waikoropupū Springs, was buried on Parapara Peak until she was called forth to guard the waterways and caves of Waikoropupū Springs. The pure water of the Springs is the spiritual and physical source of life.1

The freshwater springs are the largest cold water springs in the Southern Hemisphere2 and second only to the Antarctica’s Weddell Sea in clarity. Every second between 10,000 and 14,0003 litres of water are released from the springs, whose depth has never been accurately determined.

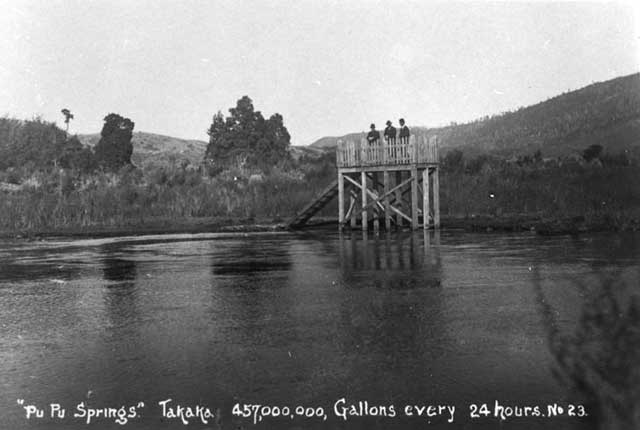

The Waikoropupū Springs Scenic Reserve is managed by the Department of Conservation4 and is Golden Bay’s most visited attraction. A walkway meanders through regenerating forest, and a platform on the edge of the springs allows visitors to look through a glass-bottomed viewer at the diverse plant and invertebrate life that thrives in the constant 11.7°C water.5

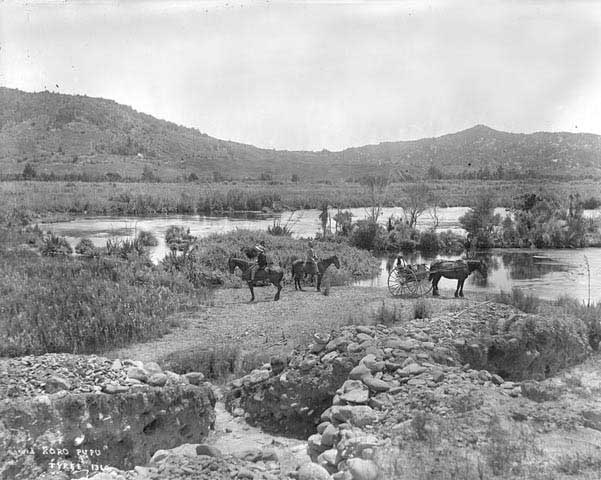

Serene and beautiful, the Springs and surrounding area were turned upside down by European and Chinese prospectors in the late 1850s, when gold was discovered in the nearby Anatoki River. By the early 1860s the native lowland bush and trees had been burned and cleared for alluvial prospecting. Water races were constructed to carry water from the spring's creeks for ground sluicing. Boulders were moved and washed for traces of gold and then stacked into walls. Hopes were high but returns were not, and within a few years most prospectors were gone.6

There is little left to show of those who searched for gold at Waikoropupū, but visitors to the springs can still see the tail races, dug to move water for sluicing, and the remains of the rock walls.

At the nearby Pupu Hydro Walkway they can see the 3km long water race used in a more ambitious gold mining project in the early 1900s. The Tākaka Sluicing Company was set up in 1901 to intensively mine for gold at the commonly referred to area, "the Bubu". A 3.7km gravity fed water race that was part canal and part aqueduct, and certainly an engineering feat, was finished above Campbell’s Creek in 1902. The company closed in 1910 when mining became uneconomical.7

A new use for the old goldmining operation was found in 1929 when the Golden Bay Electric Power Board opened a hydro power station and used the old water race to generate power for the Tākaka area. The smallest power station linked to the national grid closed in 1981, when it was decided repairs were too expensive. The Pupu Hydro Society took it over, however, and restored the old power station, restarting power generation in 1988.8

In 1981 a public walkway was constructed from the powerhouse to the water race. It then follows the race to a lookout and a weir. In the same year the station and walkway were recognised as an historic site by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust. The Pupu Hydro Society purchased the station from Tasman Energy in 1990 and annually supplies .8 gig of power to the national grid.9

In December 2013 Ngāti Tama ki te Waipounamu Trust and Andrew Yuill applied for a water conservation order for Te Waikoropupū Springs and associated waterbodies under the Resource Management Act 1991. This was the start of an almost ten-year process through the Environment Court that resulted in Te Puna Waiora o Te Waikoropupū Springs and the Wharepapa Arthur Marble Aquifer Water Conservation Order 2023. A water conservation order is the highest level of legal protection for a waterway in Aotearoa New Zealand. The order recognises the outstanding values of Te Waikoropupū Springs and protects it by imposing restrictions on activities that would negatively affect it. Under the order the Tasman District Council is required to protect the springs and to work with Manawhenua Iwi to achieve this goal.10

The introduction of the Fast Track Approvals Bill in March 2024 (which passed into law in December 2024), meant that the area was under threat due to an application by Australian company Siren's Gold to tunnel into the Sam's Creek area for ore using an opencast method. A petition"Save our Springs" was started and had received 2,782 signatures by April 2025. A movie 'Sam's creek - Fast track to desecration' was made to spread the message. At the time of writing (2025) Sam's Creek has missed out on pre-approval to begin mining but they can apply in the future to be fast-tracked without notifying the community.

2008 (updated April 2025)

Story by: Karen Stade

Sources

- Department of Conservation (2009) Waikoropupu Management Plan:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/our-policies-and-plans/statutory-plans/statutory-plan-publications/conservation-management-plans/te-waikoropupu-springs-management-plan/

Te Tau Ihu Statutory Acknowledgements 2014, Nelson City Council, Tasman District Council, Marlborough District Council, pp. 87,115

https://www.nelsonpubliclibraries.co.nz/repository/libraries/id:2p22ztlff17q9spoqdo8/hierarchy/%28Research%29%20Exisiting%20Website%20Content/TeTauIhu-StatutoryAcknowledgements.pdf - Department of Conservation.(n.d) Te Waikoropupū Springs:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/takaka-area/te-waikoropupu-springs/?tab-id=50578 - Department of Conservation (2008) Waikoropupu Springs Fact Sheet .

- Department of Conservation website

http://www.doc.govt.nz/ - Department of Conservation (2008) Waikoropupu Management Plan.

- Turley, Cliff (2005). From Bubu to Pupu, the Unique Story of the Waikoropupu Springs and Valley. Takaka, New Zealand: Golden Bay Museum, pp.4-5.

- Turley, pp.7-9, 15

- Turley, pp.10-11.

- Turley, p.11.

- Ministry for the Environment. (2023). Waikoropupū Springs water conservation order.

https://environment.govt.nz/acts-and-regulations/water-conservation-orders/waikoropupu-springs-water-conservation-order-2023/

Further Sources

Books

- Lucas Associates. (1999). Te Waikoropupu: A plan developed for Department of Conservation and Tasman District Council. Christchurch, N.Z. : Lucas Associates (available at Tasman District Library)

- Michaelis, Frances B. (1974). The ecology of the Waikoropupu springs: a thesis presented for the degree of P.H.D. in zoology. Christchurch, New Zealand: University of Canterbury.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/153878368 - Newport, J. N. W. (1975). Golden Bay, one hundred years of local government. Takaka, N. Z.: Golden Bay County Council, p.55-56.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4809463 - Shaw, D. (1986). Golden Bay walks. Nelson, N. Z: Nikau Press, (pp. 19-20)

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154607011 - Turley, C. (2005). From Bubu to Pupu, the unique story of Waikoropupu Springs and valley. Takaka, N. Z: Golden Bay Museum.

Newspapers

Ask at your local library about online access to full-text newspaper articles from 1986-

- Barrett, P. (2001, November ). Pupu walkway, Golden Bay. New Zealand Wilderness, p.53.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/173445305 - Christian, P. (2000, 27 April). Small hydro utility fears shutdown. The Press, p.4.

- Controversial plans gain consent. (2008, 3 November). The Nelson Mail, p.1.

- Daniell, S. (1996, 9 December). Taking the plunge at Pupu Springs. The Dominion Post, p.19

- Hindmarsh, G. (1999, 15 May ). Clearwater revival. New Zealand Listener, Vol.168, Issue 3079, p.32.

- Hindmarsh, G. (2006, 25 March ). Spring fever. The Nelson Mail, p.17.

- Hindmarsh, G. (2021, August 21) Society still power crazy after 40 years. Nelson Mail on Stuff:

https://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/126083327/society-still-power-crazy-after-40-years - Murdoch, H. (2007, 11 January). ‘Didymo cells flow along Takaka. The Press, p. A4.

- Pupu Hydro Scheme Historic Area (2003, 1 August ). Heritage New Zealand, Issue 90, p.53.

- Pupu hydro restorer mourned in Takaka. (2003, 1 November ) The Nelson Mail, p.14.

- Pupu Springs ban could be extended’ (2008, 18 July ). The Nelson Mail, p.3.

- Sparrow, B. (2003, 18 September ). Cuts would reduce output. The Nelson Mail, p.12.

- Sparrow, B. (2003, 8 October). Hydro scheme granted consents. The Nelson Mail, p.5.

Websites

- Department of Conservation (2009) Waikoropupu Management Plan:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/our-policies-and-plans/statutory-plans/statutory-plan-publications/conservation-management-plans/te-waikoropupu-springs-management-plan/ - Department of Conservation: Nelson Marlborough Conservancy (2007). Walks in Golden Bay (pp. 8-10) Retrieved 14 October 2008, from:

http://www.doc.govt.nz/upload/documents/parks-and-recreation/tracks-and-walks/nelson-marlborough/walks-in-golden-bay.pdf - Department of Conservation.(n.d) Te Waikoropupū Springs.

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/takaka-area/te-waikoropupu-springs/?tab-id=50578 - Department of Conservation (n.d.) Pupu Hydro Walkway.from:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/nelson-tasman/places/kahurangi-national-park/things-to-do/tracks/pupu-hydro-walkway/ - McCracken (2003) Pupu Hydro Scheme Historic Area. Retrieved 14 October 2008, from New Zealand Historic Places Trust:

https://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/7519 - Pupu Hydro Power Scheme. Retrieved from Wikipedia 29 December 2020:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pupu_Hydro_Power_Scheme - Save Our Springs petition and short film https://www.saveoursprings.nz/

Pupu Springs c.1889-1893, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection, 182242/3

Pupu Springs c.1889-1893, The Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection, 182242/3 An early viewing platform, The Nelson Provincial Museum

An early viewing platform, The Nelson Provincial Museum Waikoropupū Spring viewing platform - Karen Stade

Waikoropupū Spring viewing platform - Karen Stade Waikoropupū Springs - Karen Stade

Waikoropupū Springs - Karen Stade Waikoropupū Springs walkway - Photo - Lindsay Vaughan

Waikoropupū Springs walkway - Photo - Lindsay Vaughan