Sarau and the German Settlers of the Moutere district

The German immigrants who settled in Sarau overcame early hardships to establish a thriving agricultural community, which has remained rooted in its German heritage for over 170 years. Despite challenges during the world wars and initial difficulties with the land, the region is now renowned for its agricultural success, particularly in viticulture.

Growing Sarau from the German Roots up

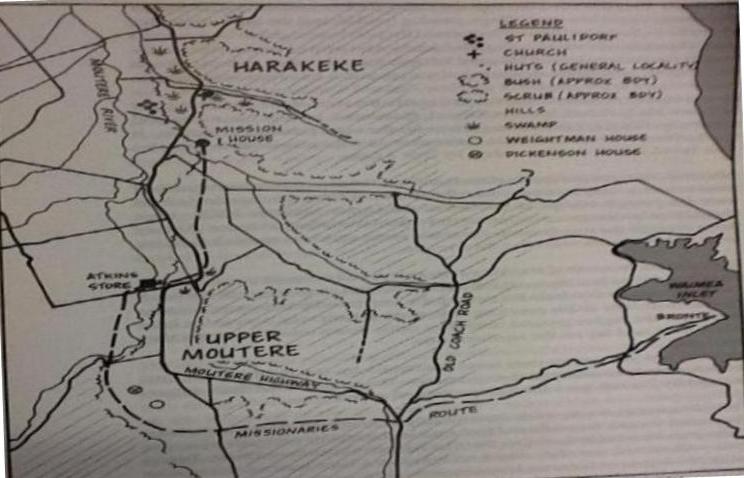

The 12,000-mile voyage of the St. Pauli from Hamburg, Germany to Nelson, New Zealand, in 1843 resulted in the eventual establishment of the village of Sarau in the Moutere Valley, led by four Lutheran missionaries. The determination of the German immigrants led to an attempt to call Upper Moutere home; however, limited understanding of New Zealand conditions resulted in its failure. But their determination paid off in their second attempt to establish a community in Moutere. 170 years later, Moutere has retained its German roots due to Sarau's success, with many residents being descendants of the first settlers. The community's success is celebrated to this day, with the Sarau Festival occurring annually and the Hans Eggers family reunion of March 2013. German settlement in Sarau made a big contribution to the boom of the agricultural industry in the Nelson region - settlement which began partly as a chance for people to escape militaristic Germany and begin a new life in New Zealand.

In the 1800's, 20,000 Germans were leaving their home country annually, to escape1 poverty and oppression, which was causing rural families to abandon their homes. The propaganda generated by the New Zealand Company was directed at Germans, because they were seen as 'persevering, industrious and sober'.2 They were enticed with free passage and the prospect of work and independence. On 12th May 1839, New Zealand Company representatives from Germany left on the barque Tory from London, sailing to Nelson to buy land. They purchased 80,000 hectares of land and divided it into 1000 allotments.

The settlement of the St. Pauli passengers had originally been planned for the Chatham Islands, but after realising that it was an illegal transaction, New Zealand Company agent, Johann Nicholas Beit, persuaded future settlers to consider Nelson instead. Because of the Germans' reputation, their arrival in Nelson was well received, as the Nelson Examiner reported, "No immigrants are more valuable than the Germans and we hail the announcement of the intended cultivation of the vine with unfeigned pleasure."3 The settlers' hopes of Nelson were high, as 116 German immigrants set out for Nelson on the 380-ton St. Pauli, on 26th December 1842, after a week's harbouring in the Elbe due to poor weather.

The Missionaries

The presence of the four missionaries, led by J.C. Riemenschneider, was well-received. They gave school lessons onboard and ministered five weddings whilst at sea to escape marriage fees. One man, whose presence was not as welcome, was Johann Beit, being the only capitalist onboard the ship amongst middle-class freemen from a range of professions. This was only the start of discontent, with Beit taking it upon himself to halve passengers' rations due to seasickness, persecuting any protestors by clamping them in irons. Missionary Heine described Beit as, "a fat, arrogant man."4 On arrival in Nelson on 16th June 1843 Beit refused to employ St. Pauli immigrants, after abdicating his responsibilities as a Company agent and setting himself up as a merchant.

The 'North German Missionary Society' had purchased a section to start a Lutheran mission for Māori, however the section was in Upper Moutere, further out than expected. This may have been seen as an annoyance but, as there were few Māori to be found in Nelson, missionaries Wohlers and Trost made the journey to Moutere to survey their section.

On 29th June 1843 Wohlers and Trost were shown around their section by William Dickenson, one of Moutere's first landowners and, a month later, the missionary house was built with the objective of cultivating potatoes to support themselves. At the time Moutere was not favoured as a settlement, due to unsuitable swampland. Local Māori used Moutere for seasonal food gathering and communication routes, and the only Māori the missionaries came across in Moutere were those they traded with. Wohlers stated how ironic it was that 'instead of preaching to the Māori, they conducted business transactions with them.'5

Without a church the missionaries took mass at their section on 10th September 1843. This helped to maintain settlers' morale as they coped with unfavourable conditions, poor soil and floods. Floods were common, destroying crops which already proved difficult to grow. A drought in mid-spring 1844 caused further problems, however the laying of the Lutheran church's foundation on 16th June caused a rebirth of confidence in the settlement. This was soon overturned, however, with three of the missionaries (besides Heine) leaving Nelson for better opportunities. The flood of October 1844 caused settlers to vacate Moutere, leaving for either Waimea, the North Island or Australia within sixteen months. Heine thought the failure of Moutere was the fault of Beit, due to his refusal of employment and promise that a Moutere settlement was possible.'6

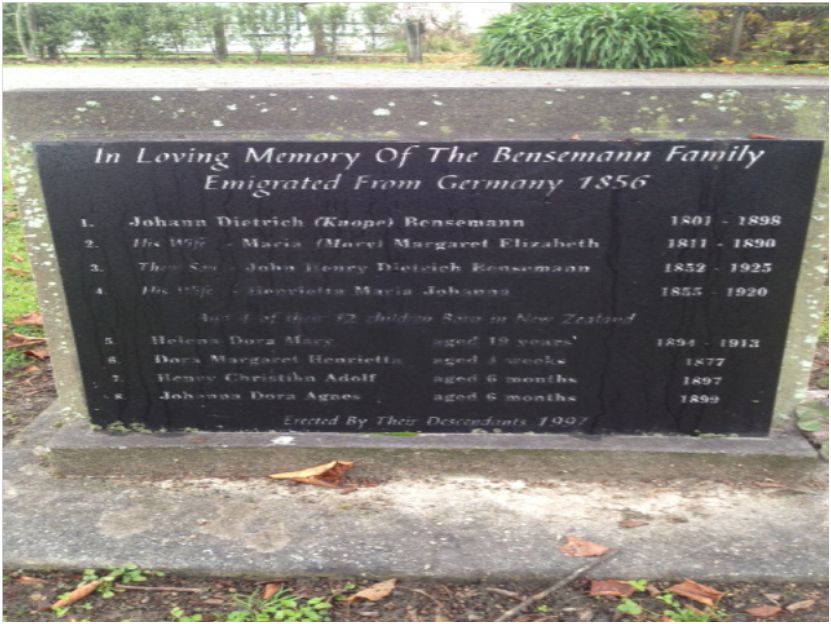

On 1st September 1844, the Skiold docked in Nelson from Hamburg, with 135 German immigrants. Led by Fedor and Carl Kelling, these agents were described as 'kind and generous benefactors.'7 They joined the Ranzau settlement (which is now called Hope). The Bensemanns were among the St. Pauli migrants who had settled in Ranzau, proving to be an asset to the German community. In 1849, Heine exchanged the Lutheran site in Ranzau for two sections in Moutere, entrusting an 80-hectare site to the Bensemanns with seven years to repay him. The next July the Bensemanns moved to Moutere, constructing a house and, in 1853, adding a two-story wing which still stands as the Moutere Inn. An annual £5 bush licence allowed the accommodation of visitors, which provided a stable income for the Bensemanns once the Moutere highway was redirected through the village, which was called Sarau after a northern German village. On 5th January 1859, visitor, Sir Julius Von Haast said of the inn: "Instead of the uncomfortable English bar, we had a cheerful typical German guest room before us...".8 The Bensemanns were vital to Sarau's development. Cordt Bensemann was on the school committee and second in command to Carl Kelling of the Moutere branch of Nelson Volunteer Corps. His daughter, Anna, married Pastor Heine in 1849 and aided the sick and elderly in Sarau.

The Heines moved to Sarau in 1853 building a fifteen roomed house, the largest serving as a church and classroom. All lessons were taught in German until the 1900's, as all 24 pupils were German. Some of them came from Neudorf and Rosenthal, within walking distance of Sarau.9 School was held at the Heine residence until 1856, when a school was built next door - a school which also accommodated English pupils. The Examiner reported on the school on 6th August 1864: 'all children are of German origin...' and later on reporting, "it is very possible to spare helpless children many tears."10 However, church services continued to be held at Heine's home until 22nd February 1860, when the community met to discuss a church building. On 25th May 1863, this matter was finalised with plans to build a church on thirty acres of land, which the Lutheran Trust Board donated to Sarau in 1853. On 2nd November 1864, the foundations for St. Paul's church were laid and, as a celebration, Sarau paid £25 for a 250-kilogram German church bell, named 'Anna', after Anna Heine. The bell rang every Saturday to mark the end of the working week and has continued to ring since 1878 to call Lutherans to service.

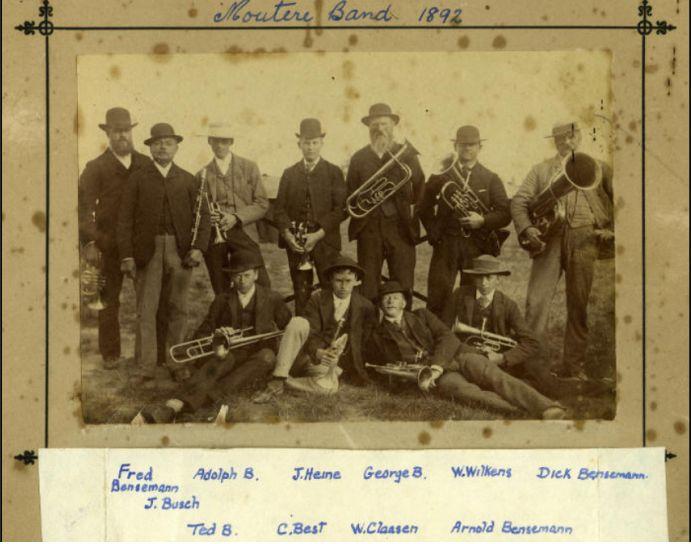

After the unification of the German Empire in 1871, the settlement of Sarau received few additional immigrants, but the community continued to prosper, with sawmills and flax-mills providing employment for men and materials for farming. The integration of Sarau with the outside world continued, as reported by the Examiner on 5th January 1859, with the opening of a six-mile road between Motueka and Sarau, with a three-mile dirt track connecting the unfinished portion.11 Whilst this enabled travel between districts, communication via telephone was of not possible. A correspondent from Sarau wrote a complaint to the Nelson Evening Mail on 12th August 1882 stating that, "a government official came amongst us at Upper Moutere with the intelligence that the government were willing...to place us in communication with the outer world by telephone, provided that the inhabitants erected a suitable office..."12 As an office had been constructed, they were displeased with the lack of communication. There was also no electricity until 1948.

World Wars

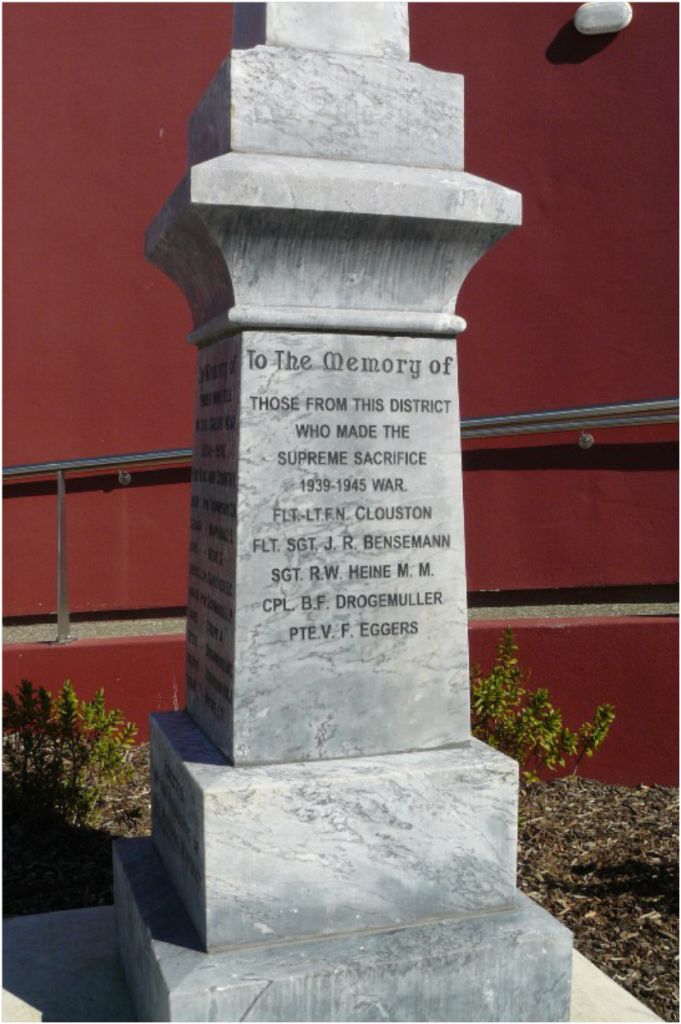

World War I had a significant impact on German descendants inhabiting Sarau, with suspicion coming from outside the district, pressuring descendants to declare their patriotism for Britain. Whilst those living in Sarau had been there for thirty years before WWI13, and the men fought for New Zealand, they were declared as 'enemy aliens'. This was seen as necessary, for 'better conduct of war' and to control those who presented a 'menace to society.'14

The Patriotic League assisted with the control of Germans, with a Nelson group making an attempt to have all people of German origin imprisoned. Newspapers received letters from anti-Germans, one stating, "A German is a German if he has any of that blood in his veins, naturalised or unnaturalised."15 National discrimination resulted in families anglicising their names, and also the renaming of Sarau village, which became 'Upper Moutere' in 1917. Furthermore, the abuse led to membership of the Lutheran church dropping, not rising again until after WWII. German was also being dropped as the language of service in 1905. Even though Moutere gave a wartime contribution of £1891, 7 shillings and fourpence,16 the district continued to suffer much abuse, causing a dramatic decline in German cultural practices.

Agriculture

The first settlers in Upper Moutere played a significant role in developing agriculture. Tobacco had been grown commercially since 1888, but in 1930-60 the industry thrived with machinery eliminating hand weeding in the 1950's which, whilst reducing wages, increased mechanisation and capitalisation, bringing Moutere into the modern era. During 1914, 55 of the 86 Moutere families17 were hop growers, however the prohibitionist movement of the era decreased hop manufacturing, which did not pick up again until the 1960's.

In contrast to a report from the 1800's that Germans were not able to succeed in viticulture, Weingut Seifrieds' vineyard was established in Moutere in 1973, attracted by the gentle north facing slopes. In 1895, the Australian viticulturist, Romeo Bragato, wrote that 'the oak trees he saw in Moutere were the best outside of Europe, therefore would be suitable for wine casks if New Zealand were to become a winery-based country.'18 At the time, this advice was not taken up, although now Moutere is renowned for the quality of its wine. Nowadays, many descendants of the original settlers are farmers in Moutere, continuing the district's reputation for crops and wine.

Sarau was founded with limited knowledge of the district, which many blamed on the New Zealand Company's inadequate agent, Beit. But the settlers learned from their mistakes and overcame many difficulties under the leadership of Pastor Heine, accomplishing what previous settlers had not. Throughout both World Wars, Moutere remained faithful to New Zealand, donating more to the wartime fund than any other district nationally, even when suffering abuse from the public. Nowadays, Moutere has a national reputation for its agricultural produce; the fertile slopes are in marked contrast to the swamplands of the 1800's. The German settlers have played a major part in this transformation.

Jade Le Petit, Nelson College for Girls, 2013.

Updated March 25, 2025

Story by: Jade Le Petit

Sources

- Briars. J. & Leith. J. (1993). The Road to Sarau Nelson, N.Z.: J. Briars and J. Leith, p. 1 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39818669

- Briars & Leith, p.6

- German Emigration to New Zealand (1843, May 27) Nelson Examiner & New Zealand Chronicle, p.255

- The Prow - German Settlement in Nelson

- Briars & Leith, p.72

- Yates. L.L. The First German Settlement in Moutere.(Heine's letter to NZ Co) Retrieved from What happened to the St Pauli, 28 May 2013.

- The Prow - German Settlement in Nelson

- Moutere Inn A History of the Moutere Inn – 1850. Retrieved from Moutere Inn, 13 May 2013

https://www.moutereinn.co.nz/history.html - Briars & Leith, p.117

- News of the Day (1864, August 6). Nelson Examiner & New Zealand Chronicle, p.3

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18640806.2.8 - Local Intelligence (1859, January 5). Nelson Examiner & New Zealand Chronicle, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18590105.2.7 - Nelson Evening Mail (1882, August 12). Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NEM18820812.2.7 - Jenny Leith Interview

- Bassett. J. Colonial Justice -The Treatment of Dalmatians in NZ during the First World War. (chapter 5). Retrieved from NZ Journal of History, 9 June 2013.

- The Prow - Nelson School of Music

- McMurtry. G. (2000) The Extended Community. Upper Moutere, NZ: R.G.C. McMurtry, p.160

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154646275 - Moutere Inn - 1850

- Briars & Leith, p.138

Interviews

- Jenny Leith (1 June 2013) by phone

- Joanna Szczepanski, Motueka Museum (9 June 2013) by Email

- Moutere Inn (11 June 2013) by email

- Paul Bensemann (1 June 2013) by email.

Further Sources

Books

- Allan. R.M. (1965) Nelson: A history of Early Settlement. Wellington, N.Z.: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8650658 - Lash. M. (1992) Nelson Notables 1840-1940. Nelson, N.Z.: Nelson Historical Society.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/29497366 - Neale. J.E. (1982) Pioneer Passengers to Nelson by Sailing Ship, March 1842 - June 1843. Nelson, N.Z.: Anchor Press.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35763493 - Perry, C., & Bensemann, M. (2016). The Neudorf Valley: 100 years 1860-1960. Nelson, N.Z.: Clive Perry.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/987573114 - Wells. A. (2003) Nelson's Historic Country Churches. Nelson, N.Z.: Nikau Press.

https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/58595176

Newspapers

- German Emigration to New Zealand (1843, May 27). Nelson Examiner & New Zealand Chronicle, p.255.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NENZC18430527.2.10 - A Golden Wedding (1899, 27 September). Feilding Star, p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=FS18990927.2.24 - The Moutere Hills (1913, April 16). Colonist p.6.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TC19130416.2.31 - Yesterday (1897, September 1). Colonist p.2.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&cl=search&d=TC18970901.2.12

Websites

- Bade. J.N. 'Germans - Early settlements'. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

https://www.teara.govt.nz/en/germans/page-3. - Daughtrey, Cyd and Thawley, Eileen: Honour Roll -World War I. Tasman Heritage.

https://heritage.tasmanlibraries.govt.nz/nodes/view/70 - Derby. M. (2011). Diverse Christian Churches -Lutheran, Dutch Reformed & Brethren Churches. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/diverse-christian-churches/page-3 - Dunn. H. Nelson School of Music 1914-1945. The Prow.

https://www.theprow.org.nz/nelson-school-of-music - Moutere Inn A History of the Moutere Inn – 1850. Moutere Inn

https://www.moutereinn.co.nz/history.html - Unknown Featherston Camp Death Register. NZ History Online.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/featherston-camp/deaths - Walrond.C. Nelson Places -Moutere Hills & Tasman Bay. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/nelson-places/page-4.

Missionaries' route to Upper Moutere - Drawn by Julie Raharuhi 1993

Missionaries' route to Upper Moutere - Drawn by Julie Raharuhi 1993 St. Paul's Lutheran Church - Present day

St. Paul's Lutheran Church - Present day Moutere Band 1892. -Acknowledgements to Bensemann.org

Moutere Band 1892. -Acknowledgements to Bensemann.org 'In memory of those from the district who made the Supreme Sacrifice 1939-1945 war. Acknowledgments to NZ History Online

'In memory of those from the district who made the Supreme Sacrifice 1939-1945 war. Acknowledgments to NZ History Online Bensemann Memorial Upper Moutere. Photo by author

Bensemann Memorial Upper Moutere. Photo by author