Wakatū or Whakatū

Māori Names People often ask what a Māori place-name means, and try to break down parts of the name to find meaning: e. g. Motueka = motu + weka = Weka Island.

Māori Names

People often ask what a Māori place-name means, and try to break down parts of the name to find meaning: e.g. Motueka = motu + weka = Weka Island. English place-names such as Featherston and personal names such as Shakespeare provide analogies – no one would consider asking the meaning of those names, or break them down into component parts.

Motueka is in fact an ancient name transplanted from Hawaiki with Tākaka and Parapara in Mohua (Golden Bay) and Arahura on the West Coast; in Hawaiki they were the names of islands in a lagoon – T’a’a, Parapara, Ara’ura and Motue’a - preyed upon by a fearsome taniwha, Aifa’arua’i, eventually dispatched by the combined efforts of many brave warriors. A similar story transplanted to Parapara in Mohua (Golden Bay) recounts the demise of a monster, Kaiwhakaruaki, who preyed on people travelling between Motueka, Tākaka, Parapara and Arahura.

Māori place-names usually describe an important feature of the landscape, indicate a resource, commemorate a significant event, or recognise a famous tupuna (ancestor). It is more appropriate to ask of all place-names, English or Māori, “What is the significance of the name?”

Wakatū or Whakatū as the traditional name for Nelson

In Nelson we have Whakatū Marae and Wakatū Incorporation. Is one right and the other wrong? There are two stories providing possible origins for Wakatū and two for Whakatū.

Wakatū

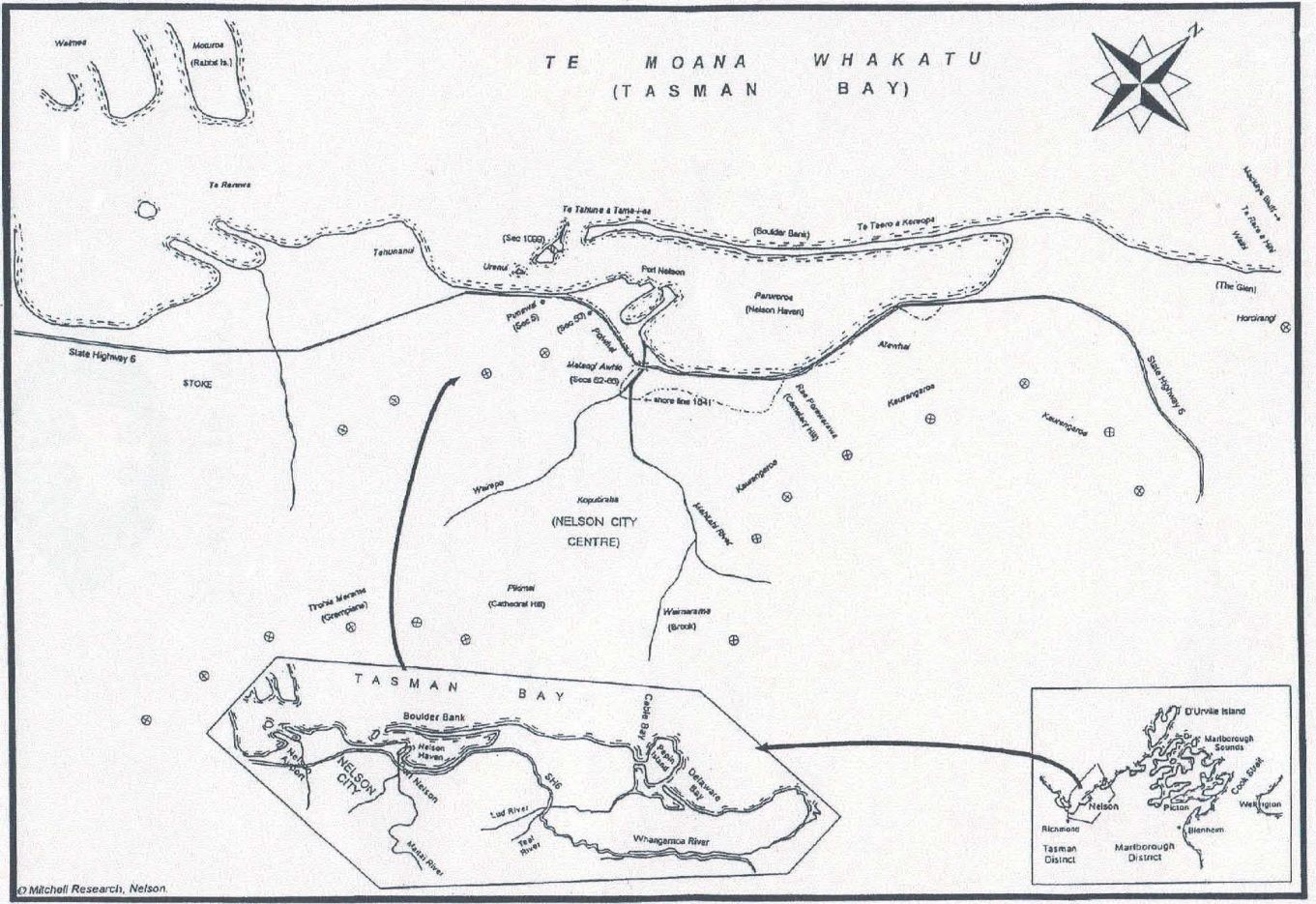

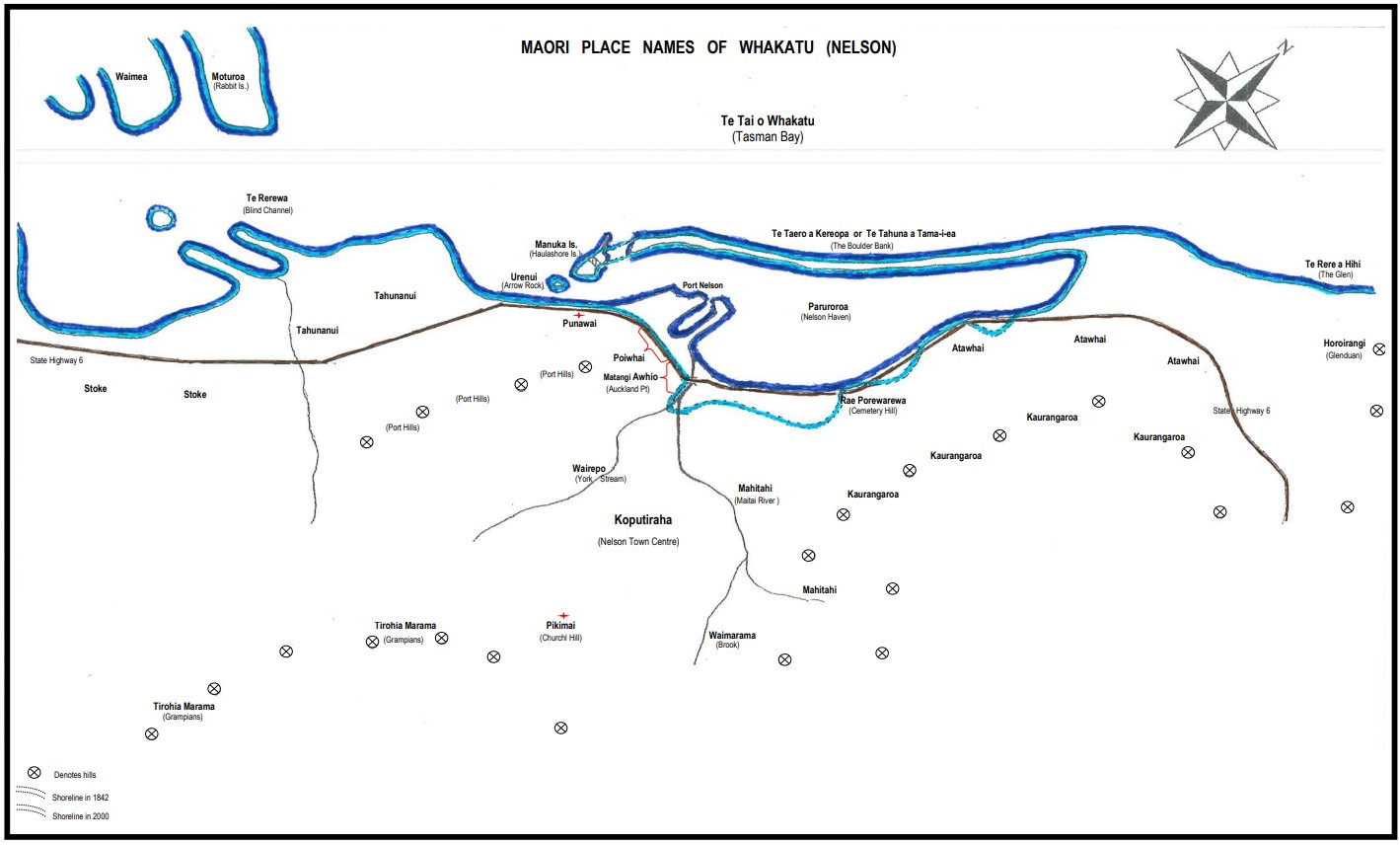

- The story of Potoru dating to the 13th - 14th centuries, is the earliest origin for the name Wakatū. Potoru was the rangatira (chief) of the waka, Te Ririno, which crossed Te Moana a Kiwa (Pacific Ocean) in company with the Aotea, captained by Turi, to as far as Rangitahua (Kermadec Islands). Turi was related to Kupe, the re-discoverer of Aotearoa. Soon after departing from Rangitahua, Potoru and Turi separated after disagreeing about the interpretation of Kupe’s sailing directions for the final leg to Aotearoa. Turi’s assessment was correct, leading him to southern Taranaki where he and his crew made safe landfall, and established the Aotea iwi, with thousands of descendants to the present day. Stubborn Potoru was not so fortunate; he encountered foul weather, forcing Te Ririno to be thrown up (tu) onto a reef with the loss of all hands. At least three accounts say that the reef was Te Taero a Kereopa – the Boulder Bank at Nelson, created by Kereopa, one of the tohunga (priests) on Kupe’s visit to the area some years earlier.

From this event – canoe (waka) thrown up (tū) and wrecked – comes Wakatū. - The story of Te Paia-i-ea (or Otama-i-ea in some accounts) is undated but must have occurred some generations after Potoru. Little is known about Te Paia, but accounts say he was a rangatira (chief) of considerable mana (status) who, on his death, was interred on the Boulder Bank at Nelson. Because of Te Paia’s status, his personal possessions, including his waka, could not be used by others after his death, and in keeping with tradition, his waka was erected (stood up – tū) as a grave marker. As well as the district name, Wakatū, one of the names for the Boulder Bank also stems from this incident: Te Tahuna o Te Paia-i-ea – The Shoal / Sandbank of Te Paia.

Whakatū

- Leprosy at Waimea - In about the mid- 16th century, disaster befell the inhabitants of the Ngāi Tara kāinga at Waimea (near the site of Appleby School); all died from the debilitating effects of leprosy – tūwhenua. Whakatū – to make, create; whenua – land, earth, soil; i.e. to become as earth … ashes to ashes, dust to dust. To commemorate this tragic event, some traditions maintain that Whakatū was adopted as a regional name.

- A kāinga at Matangi Āwhio - An old tradition recounted by kaumatua of Ngāti Kuia and Ngāti Koata offers another explanation for the locality name “Matangi Āwhio” (Auckland Point), and the wider area name spelt as “Whakatū”. The story tells of a group of manuhiri (visitors) asking locals where they can establish houses; they are told: “Whaka tū to kāinga kei te wahi e rongo ai koe i matangi a whio” i.e. Whaka – to cause, make happen, bring about, and tū – stand, stand up … whaka tū – build, erect: i.e. “Build your homes where you can hear the cries (tangi) of the whio (blue duck)”.

The identities of the residents and the visitors in this account have been lost in the mists of time.

Or is it just a matter of dialect?

Māori dialect may explain local usages today.

Tainui dialect, as brought to this region by Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Toa, tends towards the use of a “soft f” as in, for example, Whakatū Marae. And it appears from traditions recorded from elderly informants associated with Ngāti Kuia, one of the Kurahaupo iwi, that their dialects also favoured “wh”.

Taranaki dialect (Ngāti Tama and Te Atiawa) tend to pronounce as “w” – as in Wakatū Incorporation.

Story by: Mitchell Research

Further Sources

Books

- Izett, J. & Grey, G. (1904) Maori lore; the traditions of the Maori people, with the more important of their legends. Wellington, N.Z., By authority: J. Mackay, Government Printer, p.154

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1812555 - Mitchell, H & J (2004-) Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka: A History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough: Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Publishers in association with the Wakatū Incorporation.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63170610 - Tikao, T.T (1990) Tikao talks : ka taoka tapu o te ao kohatu : treasures from the ancient world of the Maori. Auckland : Penguin

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/24466427

Newspapers

- Pakauwera, E.W. & Smith, J (translator) (1917) Notes of the Ngāti Kuia tribe of New Zealand, Journal of the Polynesian Society, 26, pp.116-129

http://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=891